Physicists searching for signs of quantum gravity have long faced a frustrating problem. Even if gravity does have a quantum nature, its effects are expected to show up only at extremely small distances, far beyond the reach of experiments. A new theoretical study by Benjamin Koch and colleagues at the Technical University of Vienna in Austria suggests a different strategy. Instead of looking for quantum gravity where space–time is tiny, the researchers argue that subtle quantum effects could influence how particles and light move across huge cosmical distances.

Their work introduces a new concept called q-desics, short for quantum-corrected paths through space–time. These paths generalize the familiar trajectories predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity and could, in principle, leave observable fingerprints in cosmology and astrophysics.

General relativity and quantum mechanics are two of the most successful theories in physics, yet they describe nature in radically different ways. General relativity treats gravity as the smooth curvature of space–time, while quantum mechanics governs the probabilistic behavior of particles and fields. Reconciling the two has been one of the central challenges of theoretical physics for decades.

“One side of the problem is that one has to come up with a mathematical framework that unifies quantum mechanics and general relativity in a single consistent theory,” Koch explains. “Over many decades, numerous attempts have been made by some of the most brilliant minds humanity has to offer.” Despite this effort, no approach has yet gained universal acceptance.

Deeper difficulty

There is another, perhaps deeper difficulty. “We have little to no guidance, neither from experiments nor from observations that could tell us whether we actually are heading in the right direction or not,” Koch says. Without experimental clues, many ideas about quantum gravity remain largely speculative.

That does not mean the quest lacks value. Fundamental research often pays off in unexpected ways. “We rarely know what to expect behind the next tree in the jungle of knowledge,” Koch says. “We only can look back and realize that some of the previously explored trees provided treasures of great use and others just helped us to understand things a little better.”

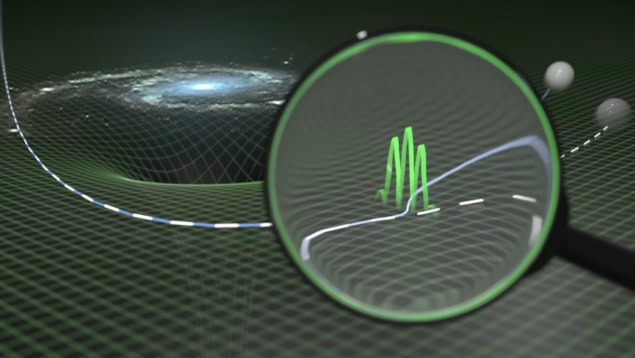

Almost every test of general relativity relies on a simple assumption. Light rays and freely falling particles follow specific paths, known as geodesics, determined entirely by the geometry of space–time. From gravitational lensing to planetary motion, this idea underpins how physicists interpret astronomical data.

Koch and his collaborators asked what happens to this assumption when space–time itself is treated as a quantum object. “Almost all interpretations of observational astrophysical and astronomical data rest on the assumption that in empty space light and particles travel on a path which is described by the geodesic equation,” Koch says. “We have shown that in the context of quantum gravity this equation has to be generalized.”

Generalized q-desic

The result is the q-desic equation. Instead of relying only on an averaged, classical picture of space–time, q-desics account for the underlying quantum structure more directly. In practical terms, this means that particles may follow paths that deviate slightly from those predicted by classical general relativity, even when space–time looks smooth on average.

Crucially, the team found that these deviations are not confined to tiny distances. “What makes our first results on the q-desics so interesting is that apart from these short distance effects, there are also long range effects possible, if one takes into account the existence of the cosmological constant,” Koch says.

This opens the door to possible tests using existing astronomical data. According to the study, q-desics could differ from ordinary geodesics over cosmological distances, affecting how matter and light propagate across the universe.

“The q-desics might be distinguished from geodesics at cosmological large distances,” Koch says, “which would be an observable manifestation of quantum gravity effects.”

Cosmological tensions

The researchers propose revisiting cosmological observations. “Currently, there are many tensions popping up between the Standard Model of cosmology and observed data,” Koch notes. “All these tensions are linked, one way or another, to the use of geodesics at vastly different distance scales.” The q-desic framework offers a new lens through which to examine such discrepancies.

Quantum gravity: we explore spin foams and other potential solutions to this enduring challenge

So far, the team has explored simplified scenarios and idealized models of quantum space–time. Extending the framework to more realistic situations will require substantial effort.

“The initial work was done with one PhD student (Ali Riahina) and one colleague (Ángel Rincón),” Koch says. “There are many things to be revisited and explored that our to-do list is growing far too long for just a few people.” One immediate goal is to encourage other researchers to engage with the idea and test it in different theoretical settings.

Whether q-desics will provide an observational window into quantum gravity remains to be seen. But by shifting attention from the smallest scales to the largest structures in the cosmos, the work offers a fresh perspective on an enduring problem.

The research is described in Physical Review D.