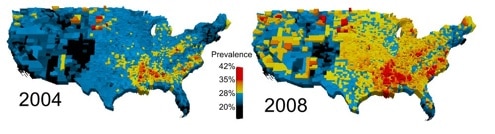

Obesity rates in the US in 2004 and 2008. (Courtesy: Lazaros Gallos)

By Margaret Harris at the APS March Meeting

The data on obesity are pretty unequivocal: we’re fat, and we’re getting fatter. Explanations for this trend, however, vary widely, with the blame alternately pinned on individual behaviour, genetics and the environment. In other words, it’s a race between “we eat too much”, “we’re born that way” and “it’s society’s fault”.

Now, research by Lazaros Gallos has come down strongly in favour of the third option. Gallos and his colleagues at City College of New York treated the obesity rates in some 3000 US counties as “particles” in a physical system, and calculated the correlation between pairs of “particles” as a function of the distance between them. This calculation allowed them to find out whether the obesity rate among, say, citizens of downtown Boston was correlated in any way to the rates in suburban Boston and more distant communities.

It wouldn’t have been particularly surprising if Gallos’ team had found such correlations on a small scale. The economies of Boston and its suburbs are tightly coupled, for one thing, and their demographics are also not so terribly different. But the data indicated that the size of the “obesity cities” – geographic regions with correlated obesity rates – was huge, up to 1000 km. In other words, the obesity rate of downtown Boston was strongly correlated not only with the rates in the city’s suburban hinterland, but also with rates in far-off New York City and hamlets in northern Maine.

This correlation was independent of the obesity rate itself – there are “thin cities” as well as obese ones – and also far stronger than correlations in other factors, such as the economy or population distribution, would suggest. The exception, intriguingly enough, was the food industry, which also showed tight correlations between geographically distant counties.

Gallos isn’t claiming that the food industry is causing obesity. He also doesn’t discount the importance of food choices and genetic factors: what you eat and who you are will clearly play a big role in determining whether or not you, as an individual, will become obese. However, he points out that our genes haven’t changed that much since the US obesity epidemic began in the 1980s, and neither, presumably, has our willpower. The difference, he says, is that on a societal level, increasingly large numbers of us are living in an “obese-o-genic” environment, and “the consensus is that the system makes you eat more”.

Gallos says he’ll post this research on arXiv sometime in the next few days [UPDATE 29/2/12: here’s the link to the paper]. In the meantime, I’ll be testing his hypothesis personally in the obese-o-genic environment of a major scientific conference, complete with multiple breakfasts, receptions and lunches. Pass the pastries, please!