Time's Pendulum: The Quest to Capture Time from Sundials to Atomic Clocks

Jo Ellen Barnett

1998 Plenum Press 280pp £16.95/$27.95hb

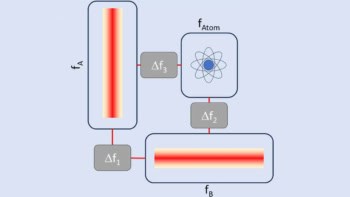

If you want to learn about atomic clocks or the sophisticated construction of an atomic timescale, then Jo Ellen Barnett’s book is not the right place. However, if you are fascinated about discovering the impact that improved time measurements have had on our daily lives and on our understanding of the world, then this is the book for you. To our knowledge the long history of clocks began about 4000 years ago in Egypt, where sundials were used to divide the daytime between sunrise and sunset into 12 equal parts. Although it was accepted that those hours changed in length over the course of a year, there was no need in those days for equal hours. Timetables for buses or trains did not exist, and organized work in factories had not yet been introduced. This situation lasted throughout the whole of antiquity for some 3000 years. Although people may not have needed accurate time measurements, the concept of time was critically discussed even then. It was generally felt that time belonged to God and could not be sold. Making money with time – for example, by making interest payments or by buying things on credit – was therefore regarded as morally doubtful. Indeed, these activities were banned by Christians, Jews and Moslems until recent times. A new era was heralded about 700 years ago with the appearance of mechanical clocks. The unequal temporary hours, which had run for more than three millennia, were finally replaced by equal hours. However, this was a problem for Christians, who felt that mechanical time had apparently lost its relation to nature, whereas in the old system prayer times were fixed. It took some time before the Church finally allowed mechanical clocks to ring 24 equal hours from its towers. The growing precision of these new clocks – driven forward by Galileo’s discovery that a pendulum swings with a constant time period and by Christiaan Huygens’ construction of the first clock to be based on this principle – finally opened the way to more practical applications. When Columbus sailed to America at the end of the 15th century, he got totally lost because at that time there was no way of measuring longitude on the open seas. Determining the difference of local times between distant places could have solved the problem, but existing clocks were not stable enough to do so. It was only some 270 years later that John Harrison constructed a marine chronometer that was good enough to do this. As a consequence of this, maps of the Earth’s surface could be drawn for the first time, showing the position of distant islands and continents with an accuracy of a few miles. However, by the end of the last century, local times – which differed from town to town – began to be a problem. More and more people were beginning to travel, and their wristwatches, the timetables of railway companies and church-tower clocks in different towns all had to be synchronized in some way. As we all know, the problem was solved by adopting the convention of a prime meridian and introducing time zones that differ by one hour every 15°. However, much local pride had to be overcome before this concept was generally accepted. Indeed, more than one country wanted to host the prime meridian and many people felt that they would lose their proper place under the sun if they had to give up their local time. The end of mechanical clocks for accurate time measurements was marked with the discovery of electromagnetism and quantum theory. Marconi’s invention of wireless telegraphy allowed distant clocks to be synchronized, thus making sophisticated marine chronometers obsolete. Quartz-crystal technology, which was applied for the first time by Warren Marrison in the 1920s, allowed cheap and accurate watches to be mass-produced. Their performance was again surpassed by the development of atomic clocks in the 1950s, in which the frequency of a quartz crystal was stabilized to a particular atomic transition. Since all atoms of the same species are identical and since any aging or frictional effects are eliminated, such clocks differ by just 10-6 s over the course of a year. Even if such accuracy is not needed in everyday life, atomic clocks are now a prerequisite for high-speed data transfer, satellite navigation and deep-space missions. Barnett not only describes the technical problems that had to be solved along this way, but also devotes a large part of her book to the consequences of accurate time measurement. This becomes particularly evident in the second part of the text, which deals with Henri Becquerel’s discovery of radioactivity and with the controversy over the age of the Earth. Whereas conventional clocks measure the present moment only, the fact that radioactive atoms decay at a constant rate allows events in the past to be dated precisely. It is surprising to learn, as we do in this book, that neither the Greeks nor other ancient cultures asked the question of the age of the Earth. Only the Bible, which talked about the creation of the world, raised the problem – and even then it got the answer badly wrong. By counting generations mentioned in the Bible, Jews and Christians believed that the Earth was no more than 4000 to 5000 years old. Even last century, when the study of fossils in different layers of sedimentary rock showed that this estimate was far too small, there was no way of evaluating the absolute age of our planet until Becquerel’s discovery came along. Today, by knowing the half-life of radioactive isotopes, and by measuring the relative proportion of decay products and parent substances in a rock or crystal, we can determine when the material formed. And since some of these isotopes have half-lives of billions of years, radiometric dating can go right back to the creation of our Earth. Studies of meteorites and of rocks gathered on the Earth and the Moon all lead to the conclusion that our planetary system began some 4.5 billion years ago. The length of time that man has been on the Earth can also be determined by similar methods. Compared with the eons that our planet has existed, humans have walked on it for a relatively short period of some million years. A clock telling us the age of the universe may not yet have been found, but Jo Ellen Barnett’s book certainly helps us to appreciate our place on our planet.