Voyager: Seeking Newer Worlds in the Third Great Age of Discovery

Stephen J Pyne

2010 Viking £18.72/$29.95hb 464pp

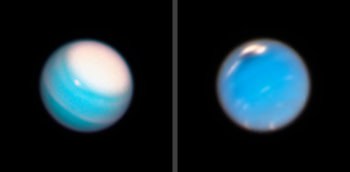

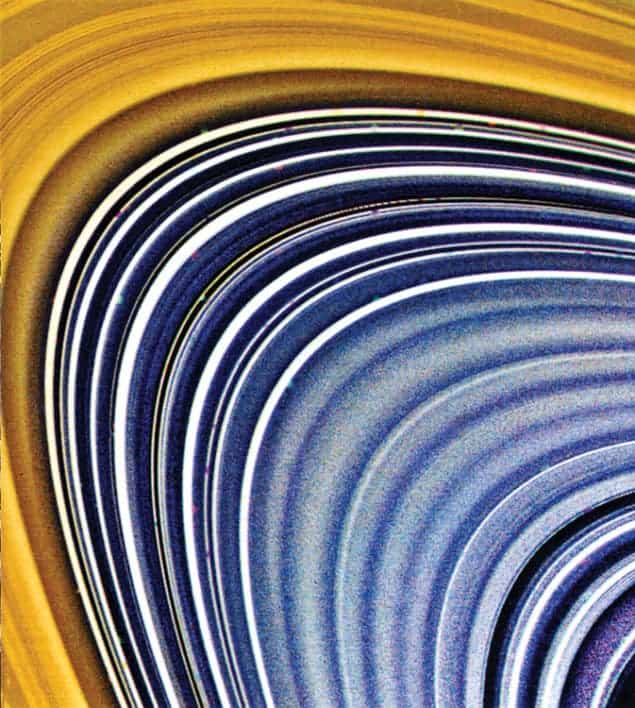

The two Voyager spacecraft have long since earned their place in the space “Hall of Fame”. Since they were launched in 1977, Voyagers 1 and 2 have investigated all the giant planets in our outer solar system, nearly 50 of their moons, and the distinctive systems of rings and magnetic fields that those planets possess. Without a shadow of doubt, their discoveries rewrote several textbooks. Some of the original analyses from these planetary fly-bys have yet to be surpassed by subsequent missions, and scientific papers involving analysis or re-analysis of Voyager science data are still being published.

On a more personal note, I can also say that Voyager 1 changed my life. Its flight past Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, in November 1981 revealed a world so intriguing that more than 20 years later another NASA spacecraft, Cassini, paid Titan a return visit. Cassini carries a project that consumed me for some 15 years: the European Huygens probe, which landed on Titan’s icy surface in 2005.

But perhaps the most astonishing thing about the two Voyagers is that their mission is not yet over. Although they were originally designed with a five-year lifespan, and were only supposed to study Jupiter and Saturn, Voyager 1 currently holds the record for being the furthest man-made object from the Earth, and some of its scientific instruments (and those of its slightly nearer sister craft) are still returning data. The Voyagers were – and are – truly heroic achievements. They form part of a series of great exploration missions undertaken by NASA, starting with the Mariner probes in the 1960s and continuing with remarkable accomplishments at Mars and Venus, as well as Jupiter and Saturn.

Stephen Pyne acknowledges all of this in his book Voyager, which is partly a history of the missions and partly a meditation on their wider significance. Pyne, a historian at Arizona State University, has meticulously researched the Voyager project and has certainly uncovered new and intriguing perspectives on this heroic undertaking. But he also suggests that his book is a study or meditation about context, one that strives to generate new understanding by emphasizing comparisons, contrasts and continuities. To this end, Pyne argues that the Voyager adventures were very much a continuation of humanity’s exploration – making their era, in the words of the book’s subtitle, the “Third Great Age of Discovery”.

Whether Pyne’s book succeeds in making this case must be left to the individual to decide, but both its breadth and depth cannot fail to entertain, perhaps even to captivate. What is less compelling to space scientists like me – though maybe not to others – is his continual insistence on comparing, contrasting and connecting the Voyager epic to the earlier explorations of Cortes, Columbus, Cook and others. It is true that such missions – whether on ancient wooden ships, overland through the uncharted interiors of Australia or the US, or indeed with the robotic explorers of our solar system – share common threads. As Pyne copiously demonstrates, all of them, Voyager included, are rooted in the economic, political, cultural and technological landscapes of their times. But his decision, at many turns, to relate the Voyager adventure to events in the previous millennium of exploration sometimes seemed unnecessarily contrived, forced and artificial, rather than demonstrating a genuine association. This is not to deny the fact that any grand undertaking such as this is a product of its wider context, but the parallels drawn in this book do seem overstretched.

Pyne does do several things well, though, and one that I found particularly intriguing was his exposition of the history of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) prior to Voyager and how the project established the JPL as the US’s (and in fact the world’s) leading centre for the exploration of our solar system. Many of the leading individuals involved in the JPL’s work are portrayed, demonstrating forcefully that such undertakings are as much about people as they are about science and technology. I can attest to this sentiment based on my own experience; the Cassini–Huygens mission that I was involved in was indeed, like Voyager, a “very human creation”. The most public face of the Voyager missions was Carl Sagan, who was a member of the imaging team. It was he, perhaps above all, who saw that this was more than just a mission of scientific discovery – it was a truly cultural endeavour and, in the broadest sense, one that could be conveyed to a very wide audience through the media.

Pyne argues that golden ages of exploration generally transition into silver ones and he suggests that this has happened in space exploration. After the grand and open-ended Voyager missions, he argues, came “complex single missions”, such as Cassini to Saturn, Huygens to Titan and various sophisticated rovers and orbiters to Mars. If we follow Pyne’s reasoning, we should probably not hark back to the golden age represented by the Voyagers. Instead, we should strive to make sure that we do not sink into a bronze age. There is a danger, of course, of this happening: neither the Voyagers nor even single-mission craft such as Cassini have the immediate utilitarian grab of missions to monitor the Earth or to provide ever-more bandwidth for our data-hungry world. Yet as we space scientists continually argue to our political masters, these grand projects of exploration do indeed drive our technology, and they also provide inspiration, especially to the young.

In the words of Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg, “The effort to understand the universe is one of the very few things that lifts human life a little above the level of farce.” As Pyne shows, the Voyagers admirably played their part in this effort.