A smorgasbord of popular-science books for your end-of-year delectation, reviewed by Margaret Harris, Hamish Johnston and Tushna Commissariat

Terrible tech

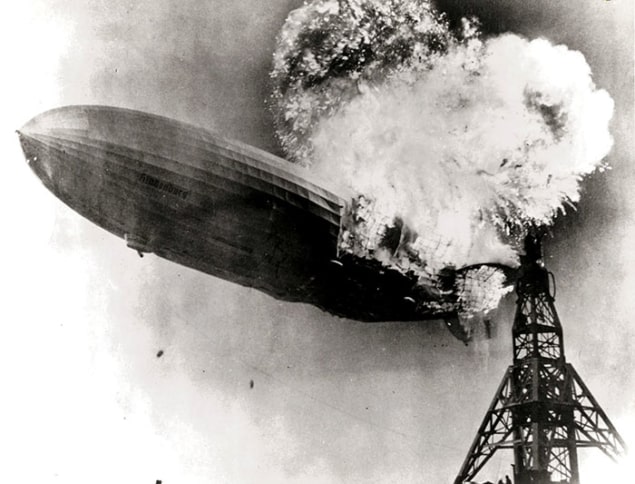

A lot of ink has been spilled trying to explain how to get good ideas out of the lab and into commercial technologies. In his book Monsters, the veteran science writer Ed Regis is interested in precisely the opposite challenge: how to prevent monumentally awful ideas from getting off the drawing board. Regis’ prime example of what he terms “pathological technologies” is the hydrogen airship, or zeppelin, which enjoyed remarkable popularity in the early 20th century despite its appalling safety record. The most famous zeppelin disaster was, of course, the Hindenburg, which caught fire and crashed during a landing attempt in 1937, killing 36 of the 97 people on board. But as Regis shows, at least nine earlier zeppelins – eight German and one British – met almost identical fates, and their American counterparts were no safer despite being filled with non-flammable helium. Regis’ tone is a lively mixture of exasperation, comic understatement and black humour, and his inventiveness in coming up with fresh denunciations for zeppelins (“a technology very much worth abandoning”) is frequently a delight. Some physicists will, however, feel their hackles rising when Regis turns his rhetorical fire on the never-completed particle accelerator known as the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC). Though the SSC was not dangerous, Regis argues that it fulfilled other criteria of a pathological technology: it was physically huge; it inspired deep, almost spiritual devotion among its proponents (some of whom still mourn its loss); the scientific risks associated with it were played down; and its enormous financial cost outweighed the benefits. This verdict seems a trifle harsh, but few will question Regis’ stance on another cancelled physics experiment: Project Plowshare. The idea behind this US-based effort was to use nuclear weapons for “peaceful” purposes, such as carving out new harbours or canals. Eventually, Regis reports, the sheer lunacy of doing civil engineering with hydrogen bombs proved too much to ignore – but only after 17 years and hundreds of millions of dollars had been poured into Plowshare and its offshoots. Now that’s pathological.

- 2015 Basic Books £19.77/$29.99hb 352pp

Quantum physicists are Go

“Astrophysics is easy,” quips a grinning Brains on the cover of Brains Explains Quantum Physics – a slim, illustrated volume in which the cerebral character from the 1960s TV series Thunderbirds takes readers on a whirlwind tour of the quantum world. The book is actually written by Ben Still, a physicist at Queen Mary University of London who works on the T2K neutrino experiment in Japan, and he/Brains begins this light-hearted chronicle by explaining that quantum mechanics did not emerge fully formed from the brain of one individual. Instead, it developed gradually as a response to contradictory and downright bizarre experimental results of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are good descriptions about how early modern physicists scratched their heads over blackbody radiation, the photoelectric effect and Rutherford scattering as the ideas of quantum mechanics were forming. The book also explains how quantum theory revolutionized the way chemists think about bonding – something that many physicists may not fully appreciate. Next on the agenda is a nice explanation of how the atomic measurements of Pieter Zeeman led Wolfgang Pauli to the concept of spin and his famous exclusion principle. Only at this point does the book return to the astrophysics promised on the cover, as Brains takes off in a Thunderbirds ship for the nearest neutron star, where he explains how quantum mechanics alone prevents some stars from collapsing into black holes. Much of the book is written in narrative form, and at times it reads like a “who’s who” of quantum physicists, emphasizing the human aspect of science. The only point where it falls down is when Brains presents a chart showing all the particles in the Standard Model of particle physics, with one very notable exception: for some reason, the Higgs boson is not on the chart. This seems an odd editorial decision for a book published well after the Higgs’ discovery in July 2012.

- 2015 Cassell £10.00hb 96pp

Cooking with maths

What does “beauty” mean in mathematics? Jim Henle, a mathematician at Smith College in the US, describes mathematical beauty as “an elusive concept, subtle, abstract and intellectual” and admits that he’s “struggled for years” to grasp it. In time, though, the answer came to him: cheesecake. He isn’t joking. In fact, one of the most endearing characteristics of Henle’s book The Proof and the Pudding: What Mathematicians, Cooks and You Have in Common is just how earnest it is. The book is a decidedly strange dish, one that combines such diverse ingredients as mathematical puzzles, recipes, homespun philosophy and a dash of self-help. By rights, it shouldn’t work. Somehow, though, it does, thanks to some fun mathematics (including a proof that the 13th of the month falls on a Friday more often than any other day) and Henle’s gently encouraging tone. In mathematics, as in cooking, he writes, “stumbling around is a method”, and the best results come to those with the right combination of confidence and humility. Sometimes unexpected combinations (such as Cambozola ice cream with salted caramel sauce) work. Often, they don’t. This is okay. Keep trying.

- 2015 Princeton University Press £18.95/$26.95hb 176pp

Feynman’s words of wisdom

So much has been said by and about the charismatic physicist Richard Feynman that it is no surprise to find that his witticisms fill a book nearly 400 pages long. The Quotable Feynman was edited and compiled by Feynman’s daughter Michelle, and it includes some 500 quotations sourced from letters, lectures, books, articles and interviews. Divided into 27 sections with labels such as “youth”, “how physicists think”, “Challenger” and, of course, “humour”, the quotations range from pithy one-liners to ponderous paragraphs. A few, such as “The thing that doesn’t fit is the most interesting”, are relatively well known, but some of the less-famous ones are just as delightful. For example, when the young Feynman discovered that Santa Claus was not real, he was apparently relieved “that there was a much simpler phenomenon to explain how so many children all over the world got presents on the same night”. Most of the quotes are not in context, and this is definitely a reference book rather than a piece of light reading. However, it does boast a wonderful selection of photographs, plus a gushingly over-the-top foreword by the particle physicist and science communicator Brian Cox. (A second foreword, by the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, is both more personal and less effusive.) All in all, the book is a good choice for those interested in the history of science, as well as a fun present for any Feynman fanboys and fangirls in your life.

- 2015, Princeton University Press, £16.95hb, 405pp

Johannes Kepler, faithful son

In December 1615, when the astronomer Johannes Kepler should have been enjoying the modest fame that followed the publication of his treatise Astronomia Nova, he was instead confronted by a family emergency. His aged mother, Katharina, stood accused of witchcraft, and powerful enemies were plotting to have her imprisoned and perhaps even killed. Ulinka Rublack’s book The Astronomer and the Witch is a detailed portrait of Katharina’s trial, the circumstances surrounding it and the role her famous son played in defending her. Both the trial and the events that led up to it are remarkably well documented and Rublack, a historian at the University of Cambridge, mines this rich seam of primary sources to place the Kepler family’s situation in context. Within the book are descriptions of the official correspondence associated with the trial; the scientific patronage system that Kepler depended on to earn his living; the outcomes of other witchcraft trials, and many other topics. Even apparently tangential aspects of Katharina’s case are given plenty of careful attention. All of this context does, however, mean that Rublack doesn’t begin to describe the actual steps that Kepler took to defend his mother until page 119, and readers without a deep interest in history (as well as science) are unlikely to get that far. Those who stick with her story, however, will gain a much deeper understanding of the life and work of one of the most influential and revered scientists of the European Renaissance.

- 2015 Oxford University Press £20.00hb 400pp

Loads of prezzies

How many gifts are given, in total, in the traditional song “The 12 Days of Christmas”? To find the answer, you could, of course, count up all the various calling birds, French hens and turtle doves by hand. However, if you and your true love have better things to do this holiday season, you might prefer to pick up Arthur Benjamin’s book The Magic of Maths: Solving for x and Figuring out Why. In a chapter on “the magic of counting”, Benjamin presents a general formula for this type of problem: on the nth day of Christmas, he explains, your true love will fork over n(n+1)/2 presents. But Benjamin, a mathematician at Harvey Mudd College in California, doesn’t stop there. Next, he shows how the gift-counting problem relates to patterns in a mathematical construct called “Pascal’s triangle” – a triangular table of numbers in which each number is the sum of the two numbers diagonally above it. And before you know it, he’s on to another, even more beautiful construction: the fractal pattern known as Sierpinski’s triangle. As soon as the reader has absorbed one “trick”, Benjamin is already moving on to the next one – and each is more dazzling than the last.

- 2015 Basic Books £9.99pb 336pp