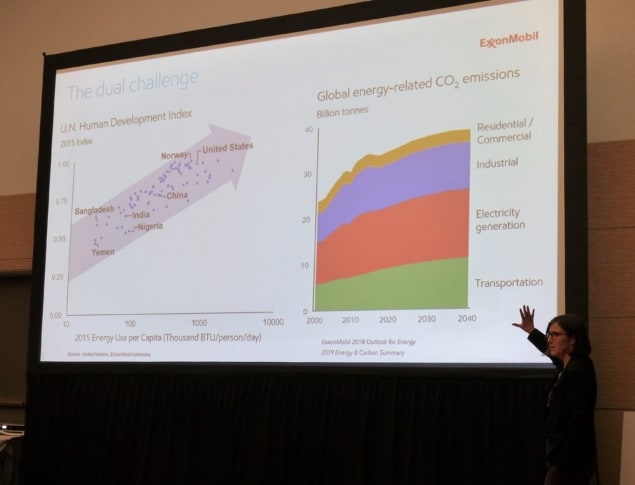

How can we satisfy the world’s energy needs while also reducing its carbon emissions?

Of all the scientific and social questions facing humanity, this is arguably the most important. Indeed, the future of our civilization may even depend on finding an answer, especially as the climate consequences of dumping carbon dioxide (CO2) into the Earth’s atmosphere become ever more apparent and alarming.

It was therefore interesting to hear this question being posed by a senior scientist at ExxonMobil, one of the world’s major oil and gas firms. In 2018, ExxonMobil announced that it plans to produce 25% more oil and gas by 2025 than it did in 2017. The company expects global demand for oil to rise by 19% between 2016 and 2040, and demand for gas to rise by 38% in the same period. In contrast, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that keeping the Earth’s temperature within 1.5 °C of pre-industrial levels would require oil and gas production to fall by 20% over the next few decades.

Amy Herhold, director of physics and mathematical sciences at ExxonMobil Research and Engineering in New Jersey, US did not mention the company’s plans for increasing production during her talk at an APS March Meeting session devoted to the company’s physics research over the last five decades. Instead, Herhold began by pointing out that the world’s population is expected to grow by 1.7 billion between 2016 and 2040. According to the company’s forecasts, demand for energy (in all forms) will go up by 25% over the same period, leading to a 10% rise in CO2 emissions. The small silver lining in this dark cloud is that CO2 production per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) is predicted to drop by 45%, as improvements in efficiency, coupled with increasing use of renewable energy, reduce the “carbon intensity” of the global economy.

Much of the rest of Herhold’s talk was devoted to an overview of the physics research that scientists at Exxon (later ExxonMobil) have done since the 1950s, on topics as varied as subsurface sensing; the behaviour of emulsions and foams; fluid flow; and even, in the early days, nuclear fusion. Towards the end, though, she returned to the subject of energy efficiency and decarbonization.

One of ExxonMobil’s current research goals is to develop membranes that can separate different types of hydrocarbons. The aim is to replace or reduce the use of distillation, in which crude oil is heated (an energy-intensive process) and successively-heavier fractions separated out. Another research project focuses on developing advanced biofuels for use in hard-to-decarbonize sectors such as commercial shipping. And a third relates to carbon capture, in which concentrated CO2 obtained from (say) the flue gas of a power plant is injected into underground rock formations to sequester it from the atmosphere.

Replacing distillation with mechanical filtration seems like a clear win for ExxonMobil; no company wants to spend money on fuel if it doesn’t have to. But it wasn’t so obvious what it stands to gain from working on carbon capture or non-fossil-fuel forms of energy, so at the end of the talk, I asked Herhold if she could elaborate.

Her response, roughly, was that ExxonMobil is an energy company, so it’s interested in all options. The company’s scientists also know a lot about underground rock formations and how fluids flow through them, so she thinks they have something to offer on carbon capture. But beyond that, Herhold was pretty tight-lipped. “What our business model looks like in the future is not something I can comment on,” she said. “It’s going to be an interesting journey.”

- This article was updated on 28th March to clarify the second paragraph.