James McKenzie examines the potential of pumps that warm our homes and offices by extracting heat from the ground below

About 15 years ago I bought a house in Cornwall. It wasn’t any ordinary house but a “future-technology” building that had been fitted with a ground-source heat pump and underfloor heating. It was a fantastic place to live in – well insulated and always cosy. As soon as my family moved in and we had unpacked, I simply had to find out how it all worked.

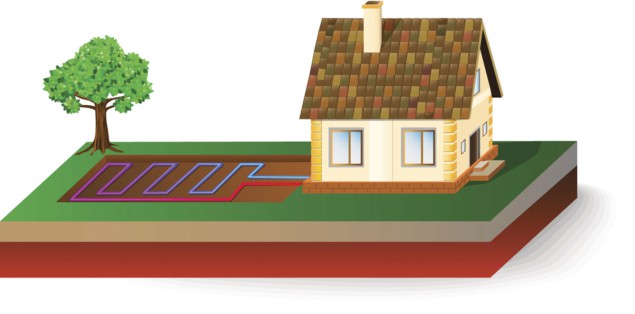

Built in 2001, the house had been fitted with a “GeoKitten” ground-source heat pump made by a local Truro-based firm called Kensa, which pioneered the adoption of the technology in the UK. The pump is a bit like a fridge that works in reverse, pulling heat in from liquid circulating through coils buried underneath my front garden. Coupled to the underfloor heating circuit, the pump made the house a fabulous place to live in, especially when winter storms were raging outside in Falmouth Bay.

Lovely warmth was sent by the pump around the house, with every room having an adjustable flow rate and precise temperature control

Lovely warmth was sent by the pump around the house, with every room having an adjustable flow rate and therefore precise temperature control. But as it was the only form of heating, I was expecting a massive electricity bill. Turns out heat pumps are incredibly efficient, with the coefficient of performance (COP) – the ratio of heat output to electrical-energy input – being about 3–4.5. My fears were unfounded.

In fact, Kensa has been a great UK success story. Founded in 1999 by two former marine engineers who’d spent years installing heat pumps on luxury yachts in the Mediterranean, the company’s products are now used in many domestic and commercial settings. Realizing they were local, I once called the owners, who kindly showed me round their factory. It was small back then, but the firm has grown and expanded. David Cameron even visited in 2009 before becoming prime minister.

Too hot to handle

Ground-source heat pumps are a great way of heating. Apart from being quiet and cheap to run, they need little maintenance and last for ages. Heat pumps will help the shift away from traditional gas- and oil-fired boilers – in fact, the UK’s recent 10-point plan for a “green industrial revolution” envisages 600,000 heat pumps being installed in Britain every year by 2028. That’ll save the equivalent of 71 million tonnes of carbon-dioxide emissions (16% of the country’s total).

Ground-source heat pumps are a great way of heating. Apart from being quiet and cheap to run, they need little maintenance and last for ages

First developed in the 1940s by an American inventor called Robert C Webber after a bizarre incident in which he burned his hand on the hot outlet pipe from his domestic deep freezer, there are now countless ground-source heat pumps around the world. Study after study has shown that such systems are both effective and efficient. The reason why they’re not the number-one choice for heating buildings is simple: the up-front costs are high.

A conventional domestic gas boiler uses about 20 kW of power and costs £50 per kilowatt, whereas a comparable ground-source of 17 kW costs more like £500/kW. Of course, if your house is well insulated you need less capacity. Costs will also fall over time as demand for such heating systems increases (regulation will be vital for that to happen). I suspect that the eventual mature market price of ground-source heat pumps will be around the £100–£200/kW mark.

That’s roughly similar to the cost of air-source heat pumps, which transfer heat from the outside air to the inside of a building and are likely to be the main competitor to ground-source pumps if gas boilers are banned. Ground-source heat pumps are harder to install. Installing the coils (or “slinkies”) in the ground has to be carefully done. You also need to dig quite a few large holes, which is tricky for anything other than a new or refurbished property.

But if your house is well insulated, as it should be, then you can expect to save money compared to an LPG boiler within seven years. Unfortunately, compared to a mains-gas system, there’s no payback at all over that time with a ground-source heat pump. Gas, despite being a carbon-dioxide-producing fossil fuel, is currently so cheap.

Green technology and growth: a vision we can believe in

And there’s the rub. People are generally poor at making long-term decisions based on a potential future payback. If it’s a choice between saving money now or in the future, most of us can only think of the here-and-now. And unless customers want to pay extra for environmentally friendly systems, house builders have no reason to invest in them. That’s why new regulations, such as those outlined in the UK’s 10-point plan, are so vital. They will force the construction industry towards this green technology.

Zeroing in

The beauty of ground-source heat pumps is that they can be fitted even in built-up areas where space is at a premium. A great example is the new headquarters of the Institute of Physics (IOP) in King’s Cross, London. It won a CIBSE building-performance award in 2020 for its green technology, which includes photovoltaics, LED lights and an advanced ground-source heat pump consisting of 10 vertical boreholes extending 60 m below the building – the first time such a system has been used anywhere in the UK.

After its first full year of operation, the system had a COP rating of 3.4 – a figure that’s likely to improve still further as the system gets tweaked and optimized. It’s a success story for the IOP, proving that the physics community is leading by example. I believe green technology and growth go hand in hand, and that, with sufficient focus, the UK can meet its net-zero-carbon goal by 2050. Thanks in part to heat pumps, we have the means to tackle the threat of climate change, which is one of the most enduring dangers that we face.