Preclinical imaging systems such as positron emission tomography (PET) scanners provide an essential tool for studying disease and assessing therapies, most commonly in mice. But as mouse organs are roughly an order of magnitude smaller than their human counterparts, sub-millimetre resolution is essential for accurate imaging and quantitative measurements within the animal’s organs and tumours.

Many radioisotopes used as PET tracers, however, emit positrons with a large range (several millimetres) and cannot be imaged at sufficiently high resolution. It is also extremely difficult to image more than one PET isotope at a time, as they all create annihilation photons with equal energy.

Now a team headed up at TU Delft aims to solve both of these challenges at once – by utilizing the prompt gamma photons that are co-emitted with positrons by many radioisotopes. Using the VECTor scanner from MILabs, the researchers demonstrate multi-isotope and sub-millimetre imaging of PET isotopes with large positron range, reporting their findings in Physics in Medicine & Biology

Exploiting prompt gammas

PET works by detecting a pair of 511 keV annihilation photons produced when a positron emitted by a radioisotope annihilates with an electron. Coincident detection of these photons enables localization of their source, by forming a line-of-response between the detectors. However, positrons with large ranges will travel in random directions away from the tracer molecule before annihilation, reducing image resolution and quantitative accuracy.

“In fact, a coincidence PET scanner performs tomography of positron annihilations instead of emissions: PAT instead of PET,” explains first author Freek Beekman. “This is not so much of an issue for [the PET isotope] 18F, due to its short positron range. But for many other isotopes important to medical research and diagnosis it results in, sometimes dramatic, blurring effects.”

Fortunately, many PET isotopes with long positron ranges also emit significant amounts of prompt gammas straight from the atom. Detecting these enables more accurate localization of the PET tracer molecules and improves the image resolution. What’s more, different PET isotopes emit prompt gammas of different energies, paving the way towards multi-tracer PET imaging.

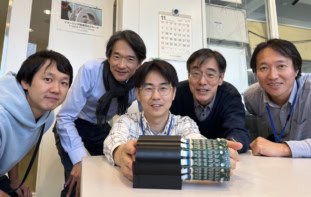

Beekman and colleagues tested this approach using a VECTor6CT system equipped with three gamma detectors and a high-energy mouse collimator with 144 pinholes (0.7 mm diameter) organized in clusters of four. The use of a clustered pinhole collimator minimizes several image-degrading effects inherent to electronic collimation.

“VECTor is the only PET technology that can precisely collimate these high-energy prompt photons and detect them,” says Beekman. “A coincidence PET scanner relying on electronic collimation could detect them, but unfortunately without collimation to the so-called line-of-response because it needs two photons in opposite direction for this.”

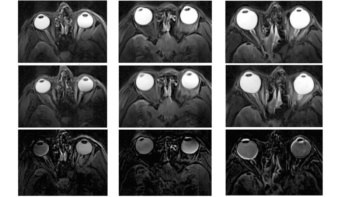

To demonstrate multi-isotope PET, the researchers injected mice with both 124I-NaI and 18F-NaF before scanning the animals for 60 min. 124I has a mean positron range of 3.4 mm, with a maximum range of 11.7 mm, but also emits large amounts of 603 keV prompt gammas. By using only the 603 keV photons for image reconstruction, sub-millimetre structures in the mouse thyroid were easily resolved.

Using the same scan but a different energy window, the researchers reconstructed high-resolution 18F-NaF images from 511 keV photons. To remove contamination from 124I annihilation photons, they corrected the 18F images by subtracting the estimated 124I signal. They then merged the corrected 18F image with the 124I image to create a clear dual-isotope mouse image showing 124I uptake in tiny thyroid parts and 18F-NaF in bone structures.

Dual-isotope PET can reduce imaging time over two separate scans, limiting the time needed to keep the animal anaesthetized, as well as providing perfectly registered images of different tracer molecules.

Resolution limits

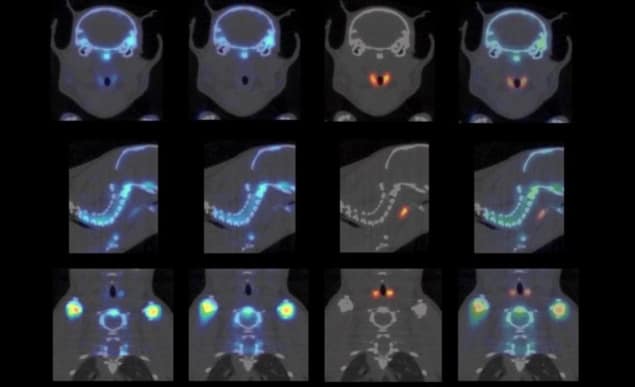

To assess image resolution, the researchers scanned a Derenzo phantom containing 0.45–0.85 mm-diameter rods filled with 124I. Comparing 124I images reconstructed using prompt gammas and annihilation photons (from the same scan) showed that the 0.75 mm rods could be clearly discerned using 603 keV photons, while the 511 keV photons did not resolve any of the rods. Simultaneous dual-isotope PET images of a phantom filled with a mix of 124I and 18F also resolved the 0.75 mm rods.

The team next imaged a quantification phantom with three compartments filled with: (1) 0.98 MBq of 124I; (2) 10.1 MBq of 18F; (3) a mix of 0.98 MBq of 124I and 10.1 MBq of 18F. The measured concentrations of 18F in compartments 2 and 3 were equal after cross-talk correction, as were the amounts of 124I in compartments 1 and 3, demonstrating high quantitative accuracy.

Finally, the researchers imaged a Derenzo phantom containing 89Zr, an important PET isotope with a mean positron range of 1.27 mm and abundant prompt gamma emission at 909 keV. Images based on 909 keV prompt gammas were far clearer than those using 511 keV photons, and could clearly resolve the 0.75 mm rods.

The team has received a grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) to develop algorithms that will further improve the images by better combining information from prompt and annihilation photons. “In addition, our partners in academia and pharmaceutical companies that have a VECTor/CT scanner are developing protocols to use this method in a large variety of new applications,” Beekman tells Physics World. “Meanwhile, we are also developing the next versions of the hardware.”