Joanne O’Meara on the benefits of injecting a little humour into physics teaching

As I strode across campus to teach my second-year electricity and magnetism class, it suddenly struck me that I had the makings of a fantastic opportunity tucked under my arm. My teaching assistant (TA) had just returned the last assignment of the semester to me, so I quickly formulated my plan. Projecting a stern and serious air as I entered the room, quite unlike my usual friendly self, I told my class that I was disappointed to hear from our TA that a lot of copying had been spotted in the submissions, which was completely unacceptable. I asked everyone to take out a piece of paper immediately and work through the solution to one question again, this time entirely on their own.

There was much muttering and sharing of furtive looks, but everyone complied as I projected the question onto the screen. After a few minutes, I said: “Please make sure you write your name and the date on the page…today is 1 April.” As my students slowly looked up at me, realization dawning on their faces, I shouted: “APRIL FOOL’S!” It took a good 10 minutes before we were all settled down and ready to discuss the physics of magnetic materials, but I maintain that it was 10 minutes well spent.

Study after study has demonstrated the value of a “flipped” classroom, in which students engage with each other and the instructor in meaningful and deep learning activities. This little April Fool’s prank was certainly not such an activity, but it is a good example of the value of being a little silly with your students: it can incentivize lecture attendance. After all, as a lecturer you go to great lengths to fine-tune your pedagogy based on current physics-education research, but unless your students actually get out of bed and into the classroom your hard work will never pay off.

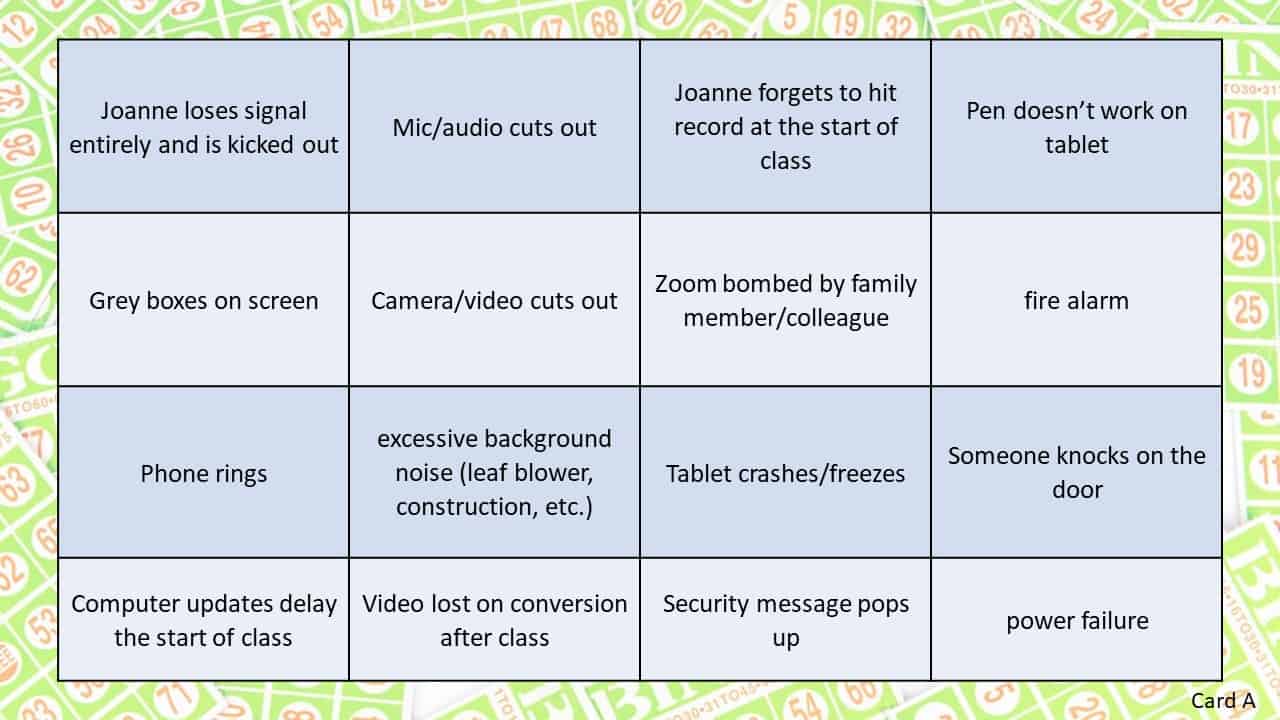

This is something I have struggled with while teaching remotely during the pandemic. Being jokey and improvisational with my students has been difficult when only a tiny fraction of the class turns their camera and/or microphone on – it is almost impossible to “read the room” in Zoom. So, after grumbling about the countless ways in which technology foils my best-laid plans for an engaging virtual class, I decided to take advantage of the humour in the situation: my students and I created a bingo game based on the myriad ways in which our online sessions go wrong, from excessive background noise to screens freezing.

Injecting humour also helps to break down barriers between my students and me. I want my classroom to be a haven, where students can ask questions (to each other and to me) without worrying about being judged. No-one, including me, has all the answers or is right all of the time; mistakes are the best opportunities for learning.

Rather than projecting an air of unassailable authority, I celebrate these moments with my students. I want them to try to follow along with each step during class, rather than passively writing it all down to figure out later. As we work, everyone is on high alert because the first person to catch a mistake, such as that inevitable loss of a negative sign, is rewarded with a box of chocolate Smarties.

With remote teaching I obviously can’t hand out sweets on the spot, so instead I keep a running tally of students who have noticed mistakes and then I post the prizes to the students at the end of term. I even add a personalized Smarties certificate to this special delivery. Students seem to really appreciate this touch – one even stuck it to their fridge – so I plan to keep this new tradition going even after we are back in the classroom.

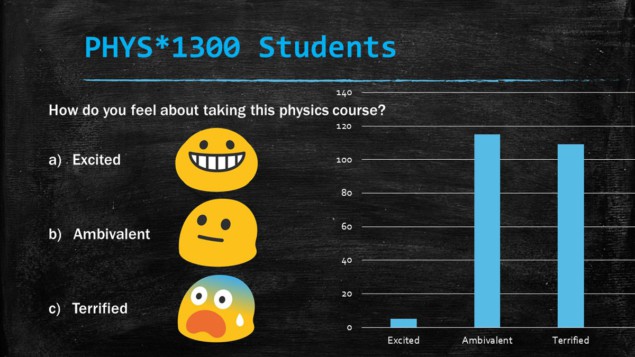

I am not a stand-up comic in academic regalia. But you don’t have to be hysterical to make good use of humour in the classroom, and humour is a great way to improve students’ attitudes to the course, which can in turn improve performance. One recent study, which looked at the effect of a positive attitude towards maths on the brain’s ability to learn and remember, concluded that children with poor attitudes towards maths rarely performed well in the subject. While that finding might not be as relevant for the physics students in my second-year electricity and magnetism class, it’s crucial for students who aren’t taking physics out of choice. I frequently find myself, for example, in front of hundreds of first-year biology students, which is like being an emissary to a hostile nation. In my first lecture, I ask them to tell me how they are feeling about this course – the choices being “excited”, “ambivalent” or “terrified”.

Humour is a great way to improve students’ attitudes, which can in turn improve performance

How we can widen career aspirations for the next generation

Unfortunately, there are times in a room full of 400 students when there are precisely zero responses in the “excited” category. Making a concerted effort to help shift our students’ attitudes towards the subject is important to opening the door for them to do well, as that positive attitude results in enhanced memory and more efficient engagement of the brain’s problem-solving capacities.

Every teacher develops their own style with practice and guidance, and I had the good fortune to be mentored by exceptional educators as I began to shape mine. I learned from some of the best in the business that humour is a powerful tool in the lecture hall for incentivizing class attendance, creating a welcoming environment and improving student attitudes. To my mind, when it comes to teaching physics, a little tomfoolery goes a long way.

- This is an edited version of an essay that was originally published in the collection Teaching Physics with a Sense of Humor.