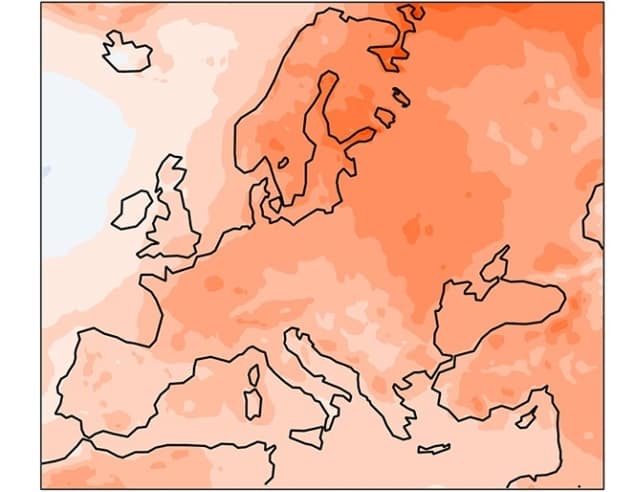

Last year was the warmest on record for Europe, in part due to an exceptionally warm winter over the northeast of the continent. It was a year that saw wildfires rage in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, while Storm Alex brought record rainfall and led to above-average river discharge across much of western Europe. These are among the key points in the European State of the Climate Report released today.

Published each April, the report brings together data from national meteorological bodies and the European Union’s Copernicus climate change service. The previous year’s weather conditions in Europe and the Arctic are analysed in the context of global climate trends, based on data from satellites, ground stations and computer modelling. “The report confirms, among other things, 2020 as the warmest year, winter and autumn on record for Europe with temperatures in winter 3.4 °C above the average,” says the report’s lead author Freja Vamborg, a climate scientist at Copernicus.

The Arctic really saw quite a spectacular year

Freja Vamborg

Despite localized temporary reductions in air pollution, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have had minimal impact on climate trends. Preliminary estimates from satellite data indicate that global atmospheric carbon dioxide level increased by 0.6%, a slightly lower rate of increase than in recent years. While methane concentrations increased by 0.8% – a higher rate than recent years – which could be linked with melting permafrost in Siberia.

Perhaps the most alarming weather occurred in Arctic Siberia, where average temperatures were 4.3 °C above the 1981–2010 reference period, almost two degrees higher than the previous record. As a result, ice cover in the adjacent Arctic seas was at record lows for most of the summer and autumn. Regional snow cover was also reduced, which is likely to have further increased local warming with less solar energy being reflected off the white surfaces.

“The Arctic really saw quite a spectacular year,” says Vamborg. “We know that the Arctic is warming at a faster rate than the global average. But on top of this long-term trend, the Arctic is also a very variable environment.” Vamborg says the short-term fluctuations means it is not inevitable that next year will be equally extreme.

‘Frightening’ findings

Europe’s climate report arrived in a busy week for climate developments. On Monday the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) released its State of the Global Climate 2020 report, stating that the average global temperature was 1.2 °C above pre-industrial levels. It was one of the three warmest years on record despite 2020 being a La Niña year when sea surface temperatures were cooler than average in the central and eastern tropical Pacific.

The WMO report estimates that 50 million people were doubly hit in 2020 by extreme weather and the COVID-19 pandemic. Evacuations, recovery and relief operations were affected by the pandemic, highlighting the need for a more integrated approach to managing climate hazards. The pandemic has also revealed cracks in global food security, as movement of goods was restricted and weather forecast services that support agriculture in the developing world were compromised.

Has the COVID-19 lockdown changed Earth’s climate?

The UN secretary general, António Guterres, described the WMO report as “frightening”. He called on governments to offer more ambitious emissions targets – referred to as nationally determined contributions – ahead of the UN climate summit in Glasgow in November (COP 26). Guterres stressed that co-operation between the US and China is vital to limiting global warming to well below 2 °C, the goal of the 2015 Paris climate accord.

China’s president Xi Jinping is among 40 world leaders invited by US president Joe Biden to attend a virtual summit on the climate crisis on 22–23 April. “We look forward to working with governments around the world to raise the level of global ambition to meet the climate challenge,” read a White House statement. Shortly ahead of the summit, the UK government announced that it would set in law a target to cut carbon emissions by 78% by 2035 compared to 1990 levels.