Steven Judge argues that it would be wrong for countries to revert to imperial measures

When I was at primary school in the 1960s, measurements were performed using traditional, or imperial, units. The ounce, pound, stone, inch, foot and so on were combined in multiples of 3, 4, 12, 14, 16 and…1760 (one mile being 1760 yards) and often had strange definitions. The furlong, for example, originated from the length that an ox-drawn plough could cover, being 220 yards.

From 1974 onwards, a welcome change occurred when it became compulsory for UK schools to teach metric units – a measurement system that made sense, based on multiples of 10. The bizarre vocabulary of different units was replaced by prefixes that were the same whether you were measuring length, time, mass or radioactivity. It is a system that is simple and works from the very small to the very large.

For this concept, we can thank the Northamptonshire-born clergyman and natural philosopher Reverend John Wilkins (1614–1672). One of the greatest thinkers of his generation, in 1668 he proposed a system of measurement based on a universal standard of length and a decimal scheme. It was one of the first concrete proposals for the metric system of measurement.

His ideas were not adopted straightaway, but Wilkins knew that, in the words of Ecclesiastes, there is a time for every matter under heaven. For the metric system, that time was the French Revolution. Measurements in France in the 18th century had been a mess, with hundreds of local systems leading to countless frauds. Fair weights and measures were one demand of the revolutionaries.

Indeed, in 1790 Talleyrand, the Bishop of Autun contacted the British Parliament to propose adopting a unified system of measurements. This putative Anglo-French co-operation was rejected by the British parliament but the French pressed ahead anyway. The advantages of the new metric system were clear and on 20 May 1875 an international treaty – the Metre Convention – was signed that established the metric system of measurements.

The convention also established the International Weights and Measures Bureau (BIPM) to co-ordinate the new scheme. One of its first jobs was to construct a standard kilogram – a metal artefact that would serve as the reference point for the world. Countries would hold a copy of the artefact, allowing industry to compare their weights to the copy. Constructing the standard kilogram proved difficult and, in fact, a British engineering firm, Johnson Matthey, was commissioned to help. The first standard kilogram, known as the International Prototype Kilogram, is at the BIPM to this day.

Yet the metric system – known as the Système International d’Unités or simply “SI” – had to expand to meet the needs of industry. It was found that only seven base units were needed (mass, length, time, electrical current, temperature, luminous intensity and amount of substance); everything else could be expressed in terms of these units. Methods were developed to realize standard units that relied only on the underlying physics.

The UK government should realize that the metric system has strong British roots and should applaud the contribution that British scientists have made, rather than perceiving it as something ‘foreign’

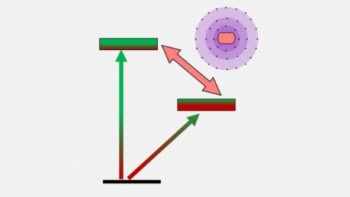

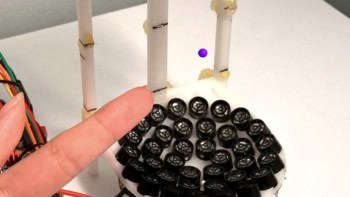

Although the kilogram remained stubbornly difficult to replace, it was a British scientist – Bryan Kibble – who helped find a solution. Based at the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, UK, he developed an ingenious balance that linked a measurement of mass to the force produced by an electrical current in a coil, and hence to the Planck constant. The standard kilogram could retire gracefully and, from 20 May 2019, all measurements were based on constants that describe the natural world. Wilkins’ vision had come to pass.

‘Foolishness beyond measure’

I mention all this because tomorrow, 20 May 2023, marks World Metrology Day. It celebrates the anniversary of the signing of the Metre Convention, which the UK signed in 1884, having legalized the use of the metric system several years earlier. The theme this year is metrology to support the global food system. This includes the rapid measurements of mass to ensure pre-packaged foods are labelled correctly, determining the isotopic composition of high-value foods (such as honey) to confirm their origin, and detecting chemical or biological contamination.

Despite the success of the metric system, there remain some politicians in the UK who – in this post-Brexit age – are actually considering whether it would be better for shops to revert to imperial units. The government even conducted a survey to gauge public opinion on a return to historical weights and measures, which received over 100,000 responses. However, existing legislation already allows shops to use traditional units, so long as metric units are also displayed.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with using the old units alongside the SI, and there is nothing in current UK regulations to forbid it. The pound is defined to be exactly 0.45359237 kg and an inch is exactly 2.54 cm, so the two systems are joined. My local pub sells beer in pints, I buy petrol in litres, give my height in feet and inches, and I use centimetres or inches when cutting up wood for DIY projects, whatever is most convenient. SI gets a makeover

Having the two systems is a compromise that has worked well for decades. Apart from the time and money wasted on the survey, the UK government is simply stirring discontent between those who want to hark back to the “good old days” and a younger generation who want to keep with the times.

The UK government should realize that the metric system has strong British roots and should applaud the contribution that British scientists have made, rather than perceiving it as something “foreign”. It should be celebrating the science of metrology and looking to the opportunities offered by developing innovative instruments based on quantum mechanics and improving productivity by introducing digitization. A harmonized measurement system is one of humanity’s greatest achievements and for any government to promote a return to the old ways is foolishness beyond measure.

In the words of the French mathematician and philosopher Marquis de Condorcet in 1791, the metric system is “for all people, for all time”.