University spin-out firms offer physicists the chance to apply their knowledge in a commercial setting, but the path to success for founders and their employees has its ups and downs, as Margaret Harris reports

When Will Reeves embarked on a PhD in fibre optics at the University of Bath in 1999, his career path seemed assured. The communications industry was booming, companies around the world were eagerly hoovering up graduates with relevant skills, and with a telecoms-friendly PhD to add to his undergraduate degree in physics, Reeves figured it would be easy to find a job in industrial research at a large firm such as Nortel Networks. The economy, however, had other ideas. By the time he completed his PhD in 2003, the telecoms industry had gone into free fall, shedding thousands of jobs in the UK alone. “Companies were making loads of redundancies and there weren’t any jobs at all in what I’d trained for,” he recalls.

Fortunately, Reeves had a plan B. As an undergraduate at Bath, he had done a year’s industrial placement at Sharp Laboratories of Europe, where he worked on liquid-crystal displays and learned some basic clean-room techniques. On the strength of that experience, he says, he got an interview in 2003 at a small but fast-growing firm called Plastic Logic, which had been founded a little over two years earlier by researchers from the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory. At the time, Plastic Logic was still trying to transform its founders’ novel work on plastic electronics into a marketable device, and Reeves was initially hired to develop techniques for measuring the performance of different components. A decade on, however, both the company and Reeves’ role within it have transformed almost beyond recognition. “It’s been quite a rollercoaster, and there have been times when we have been close to closing,” he says. “But I think actually [the telecoms crash] was a blessing in disguise because I’ve enjoyed this more than I would have enjoyed working in fibre optics.”

The physics of spin

Companies like Plastic Logic, which are founded in order to commercialize university-based research, are known as “spin-outs”, and they offer many different kinds of benefits. For physicists like Reeves, whose interests include both pure and commercial research, they are an attractive career option. For their academic founders, they are a way of getting good ideas out of the lab by drawing on resources and expertise from the commercial sphere. And of course, for universities and the sceptical politicians who fund them, spin-outs are a welcome sign that money spent on research can produce tangible benefits in the form of new products and jobs.

Spin-out firms are an attractive career option and a way of getting good ideas out of the lab

But as Reeves and others involved in spin-outs emphasize, such companies are not suited to everyone. Joining a young, untested company is risky, especially in the early years, when spin-outs are always in danger of running out of cash unless they can raise more money. As Kevin Arthur, chief executive of the solar-technology spin-out Oxford PV (see case study below) observes, “That’s something that really focuses your mind, and you’ve got to like that level of risk.” On the academic side, too, the spin-out route does not always make sense. “We all think from time to time that we have good ideas, but there are some pretty harsh things that go on commercially that have nothing to do with the goodness of the idea,” says Graham Cross, a physicist at Durham University whose spin-out firm, Farfield, initially struggled to turn a promising technology into a marketable product.

Physicists interested in working at spin-outs (or founding them) may also be at a disadvantage due to the simple fact that physics departments do not spawn as many spin-outs as their counterparts in the life sciences or engineering. And with some notable exceptions – including Oxford Instruments, which was spun out in 1959 and is now part of the FTSE 250 index of large UK companies – not many physics spin-outs grow big enough to employ large numbers of people. In 2009 Junfu Zhang, an economist at Clark University in Massachusetts, US, studied 903 academic entrepreneurs who had received funding from venture-capital companies, which invest in spin-outs with a strong potential for growth (see box). Of these high-growth spin-outs, Zhang found that fewer than 5% had founders who identified themselves as members of a physics department. In contrast, 45% came from engineering departments, while another 40% worked in the medical or biological sciences.

Start me up: three ways of funding a spin-out

Sales

Companies that make high-value, low-sales-volume goods, such as scientific instruments, can sometimes grow “organically” by using the profits from each sale to develop new products and refine existing ones. This allows founders to maintain control over their company and its future direction, but it is unlikely to provide enough money for the company to do everything it wants to do or hire everyone it wants to hire. “I made some small profit out of it [the first microscope I sold], but I was working like a dog,” says Ahmet Oral, a physicist at Turkey’s Sabancı University and founder of the Anglo-Turkish firm NanoMagnetics Instruments. After finishing his “day job”, he says, “I was going back home and working until two, three, even four in the morning, nonstop, for about six months or so. It was hard.”

Seed money

A variety of organizations, including governments, private philanthropic groups and international bodies such as the EU provide small-to-medium-sized grants for spin-outs and other early-stage companies. Although the application process for such grants is competitive, and the funds available are generally not on the same scale as business-angel or venture-capital funding (see below), they can be vital in a spin-out’s earliest stages and come with fewer strings attached. Examples in the UK include the Technology Strategy Board, the Royal Society Enterprise Fund, university-based groups such as the University Challenge Seed Fund and so-called “translational” research grants from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, although each of these organizations has different goals and rules for how monies are used. A spin-out’s parent university can also be an important source of early support by offering cheap lab space within the department or at a separate “business incubator” and by funding patent applications via the technology-transfer office.

Business angels and venture capital

At the deep-pocketed end of the funding spectrum, business angels and venture capital (VC) firms provide money in exchange for a share of the business and – especially in the case of venture capital – a say in how it is run. The principal difference between them is that angels are investing their own money, while VC firms are managing funds from a large pool of investors. However, business angels also tend to invest in businesses earlier and to provide smaller amounts of money, typically around £100,000, to help a spin-out get through the difficult early period. In contrast, “most venture capitalists, even early-stage ones, won’t come in at less than a £1–1.5m equity investment”, says Brian Tanner, dean of knowledge transfer at Durham University. “The cost of due diligence [for their investors] is sufficiently high that they want to put in cash of that sort of quantum to make it worth their while.” In order to attract that kind of money, Tanner adds, companies need a proper management team as well as an idea or product with a strong potential for growth.

Russell Cowburn, a physicist who has founded spin-outs at both Durham and Cambridge universities, says that the low number of physics spin-outs is partly due to the nature of the field. “Quite often what physicists come up with is a new type of device, and then you’re immediately hitting this problem of scale where it can only be brought to market if you sell a billion of them,” he explains. Many biotech spin-outs, he adds, avoid this problem by developing a new treatment or process and then licensing it to a larger firm.

Another possible reason for physics’ low profile in the spin-out world is that there used to be a stigma associated with getting involved in commercial ventures. Brian Tanner, a Durham physicist who founded a company called Bede Scientific Instruments in 1978, remembers his university’s then-vice-chancellor telling him, “Well, if you really want to do this, young man, that’s okay – but we thought you had a good career ahead of you.” Such official discouragement is rare to non-existent these days, but Henry Snaith, the academic founder of Oxford PV, believes that in some quarters, old attitudes die hard. “There’s a certain branch of academic scientists – physicists, mathematicians, chemists – who consider that interacting with industry is inferior to doing pure science,” he says. “They think we should just be concentrating on finding out new phenomena and understanding things, and not be so worried about real-world problems.”

Lingering traces of anti-industry sentiment aside, however, the raw statistics probably give a misleading impression of physicists’ entrepreneurial opportunities. Because physics can be applied to many different areas, physicists are often involved in firms that do not, on the face of it, appear to have a strong connection to the subject. A good example is Sphere Fluidics, which was spun out of Cambridge’s chemistry department in 2010. The company was founded to commercialize a technique for rapidly analysing single cells encased within tiny droplets and, in June 2013, it won the life-sciences category of a pan-European spin-out competition. However, the firm’s chairman Andrew Mackintosh – a physicist by training, and a former chief executive of Oxford Instruments – argues that Sphere Fluidics actually has a strong link to physics. Although the firm employs chemists to create the microdroplets and biochemists to understand the processes taking place within them, the technique for manipulating and measuring the droplets relies on optical instrumentation – and that, Mackintosh says, requires physicists. “You have to put really sophisticated teams together very early on in the life of these companies,” he says. “In many, many spin-outs, there’ll be a lot of physics underneath, because it’s about measurement and instrumentation.”

Case study: Oxford PV

While there is no such thing as a “typical” spin-out, the story (so far) of Oxford PV nevertheless includes some characteristic features. Based on research performed by University of Oxford physicist Henry Snaith, the firm’s core product is a type of solar photovoltaic (PV) cell that can be printed onto glass. It was spun out of Oxford in 2010 with the help of the university’s technology-transfer company, Isis Innovation, which funded its initial round of patents and brought in an experienced chief executive, Kevin Arthur, from the semiconductor industry.

Since then, the firm has raised more than £4m, including a total of £350,000 from the Technology Strategy Board (an organization funded by the UK government) and £3.45m from investment syndicates, including venture capital. Currently, scientists and technicians at its premises in a university-linked “business incubator” north of Oxford are working to improve the efficiency of the underlying solar-cell technology and to demonstrate that durable solar-PV glass can be produced on a commercial scale. One of Snaith’s former postdocs, Ed Crossland, joined the firm earlier this year as a senior research scientist, and the company plans to hire five new technologists before the end of 2013. In the future, Oxford PV hopes to license its product to manufacturers that can incorporate its energy-generating glass into the windows of skyscrapers, making it a ubiquitous feature of modern “green” architecture.

“I do solar-cell research because I believe that it’s the source of energy we need for the future. In some sense, it doesn’t matter which PV technology is successful as long as one of them is, but if no-one tries to push it, it’s not going to happen. My motivation is to try to get the technology out there.”

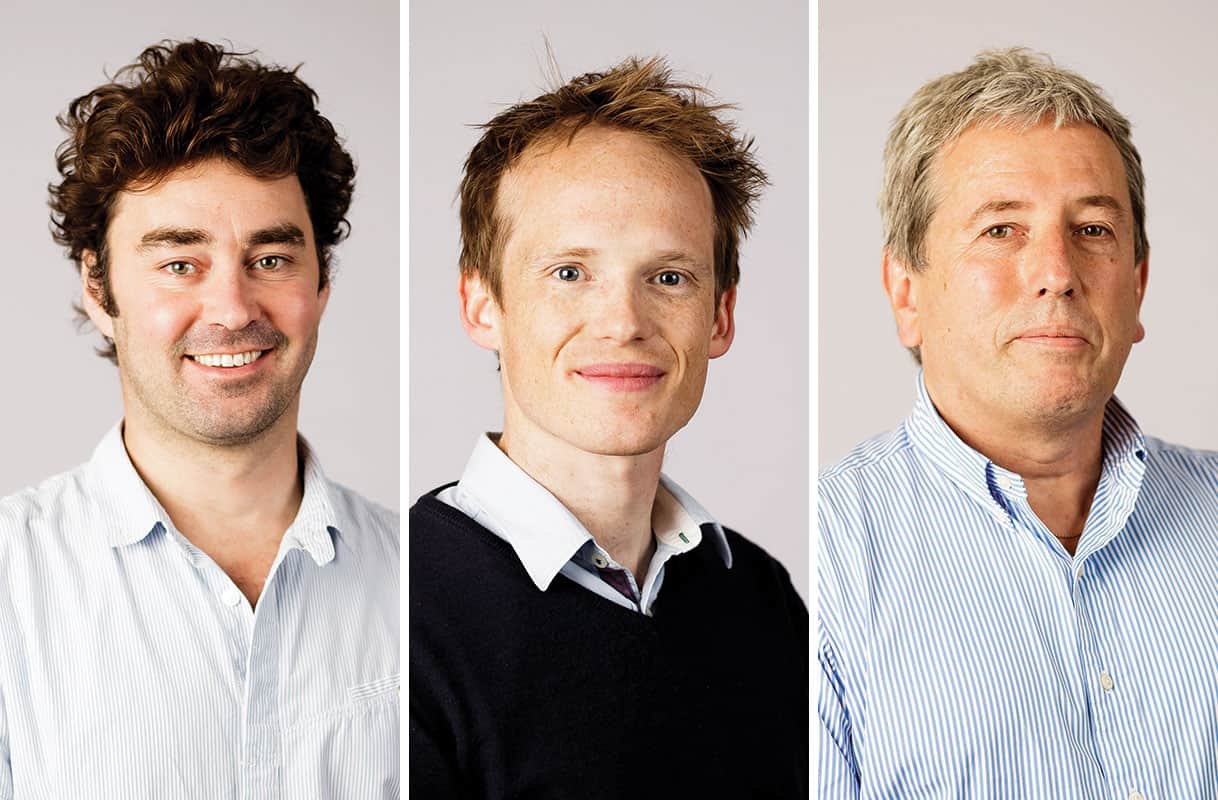

Henry Snaith, physicist and chief scientific officer

“With a technical staff of 10–15 there’s not enough hands to do everything we want to do, so I’m still in the lab pretty much every day, whether it’s with my hands wet in the fume hoods or just overseeing what’s going on.”

Ed Crossland, senior research scientist

“I really feel with this company we’re in the right place at the right time with the right technology. We’re constantly announcing updates to Henry’s technology and we’re just pushing at an open door with the construction industry, because they really want to have an energy-generating coating that they can apply to their existing materials.”

Kevin Arthur, chief executive

Risks and rewards

This need for a physicist’s skills is a positive sign for students and recent graduates interested in joining a spin-out firm. There are, however, some caveats. At their inception, spin-outs are usually little more than one- or two-person operations, and slower-growing, revenue-funded firms often remain so for years. During this earliest phase, therefore, companies will only hire new employees to do work that the founders cannot. Moreover, employment contracts are likely to be short-term, stretching only as far as the spin-out’s current round of funding permits. Marcus Swann, a former postdoctoral researcher in Cross’s group at Durham, notes ruefully that when he joined Farfield as its fourth employee, he imagined that working there might offer more long-term stability than the “serial postdoc” phase of early-career academia. In the event, he says, “I’ve been employed for 13 years now but there hasn’t been any certainty over it. At a spin-out you’ve got no idea what’s going to happen – there’s absolutely no guarantee it’s going to last more than a year.”

Yet there are rewards in getting involved early. While life at a spin-out is not, in Tanner’s words, “just a matter of swanning off with a million quid and becoming very rich”, early employees of successful spin-outs can nevertheless make a fair amount of money. To attract talent, many spin-outs offer early employees a stake in the company, and someone who helps transform a company from a start-up to a major player usually ends up with what Cowburn delicately terms “very interesting share options”.

But even spin-outs with more modest outcomes have their attractions. Farfield was sold to a Swedish instrumentation company in 2010, and the future of its core technology is now uncertain. Nevertheless, Swann says that working there has given him a huge range of experiences that he would not have had if he had stayed in academia or gone to work for a bigger firm. In addition to scientific tasks such as computer modelling and developing measurement techniques, he says, he has also been involved in product development, customer support, sales and marketing, and participated in scientific collaborations with researchers in the petroleum and pharmaceutical industries. “There’s no area of the company’s existence where I haven’t had some good visibility,” he says. “From that point of view, it’s been a tremendous learning experience. I don’t feel constrained by my scientific background any more.” Tanner, whose first spin-out fell victim to the credit crunch of 2008 and was subsequently sold to a larger company, agrees. “I don’t know of anyone who’s been in that early-stage business environment being out of work for long,” he says.

What it takes

All of the people interviewed for this article agreed that working at a spin-out requires a love of variety. For example, on the day that Reeves spoke to Physics World about his work at Plastic Logic, he had spent the morning repairing a laser cutting machine, but said that other typical tasks include computer programming, meeting clients and even creative work such as designing sample content for the company’s electronic displays.

Another thing that came up frequently was an appetite – or at least a tolerance – for responsibility as well as risk. “If you join a spin-out, you are by definition going to be a key player in that company,” says Swann. “It’s difficult to say ‘no’ because you know that if you don’t do it, it doesn’t get done.” Scientists at a spin-out also have a responsibility to stay focused on the company’s product rather than pursuing interesting tangents, says Ed Crossland, who did a postdoc in Snaith’s group at the University of Oxford and is now a senior research scientist at Oxford PV.

Scientific skills are important, too, and for that reason, opportunities at spin-outs are more extensive for those with physics PhDs than they are for BSc graduates. “To any graduate thinking of doing research in a start-up company, I’d say they should do it with the mind of working for one or two years to gain experience,” says Snaith. “But if they really want to progress in research in industry, they should then come back [to university] and do a PhD.” Cowburn suggests that undergraduates who want to get some spin-out experience should approach companies about doing a specific piece of work, such as software programming or designing a circuit, rather than seeking a traditional, training-based internship.

Regardless of their level of experience, however, prospective employees should emphasize that they have certain skills because they are a quick learner, not because it is the only thing they can do. “Being attractive to an employer means you’re smart – you’re not just an expert in doing one particular thing,” says Crossland. “You need to be a problem solver who can apply your skills and talents to whatever problem the company might have.”

Ultimately, Mackintosh believes that spin-outs are exciting places for physicists to work. “If you’re prepared for a lively ride, you have no idea where that company can go,” says Mackintosh. “Even if that company folds, the experience you gain allows you to go do the same thing in another company – probably a lot better than you did it the first time.”