Andrew Robinson reviews four books on Einstein and his theory of relativity

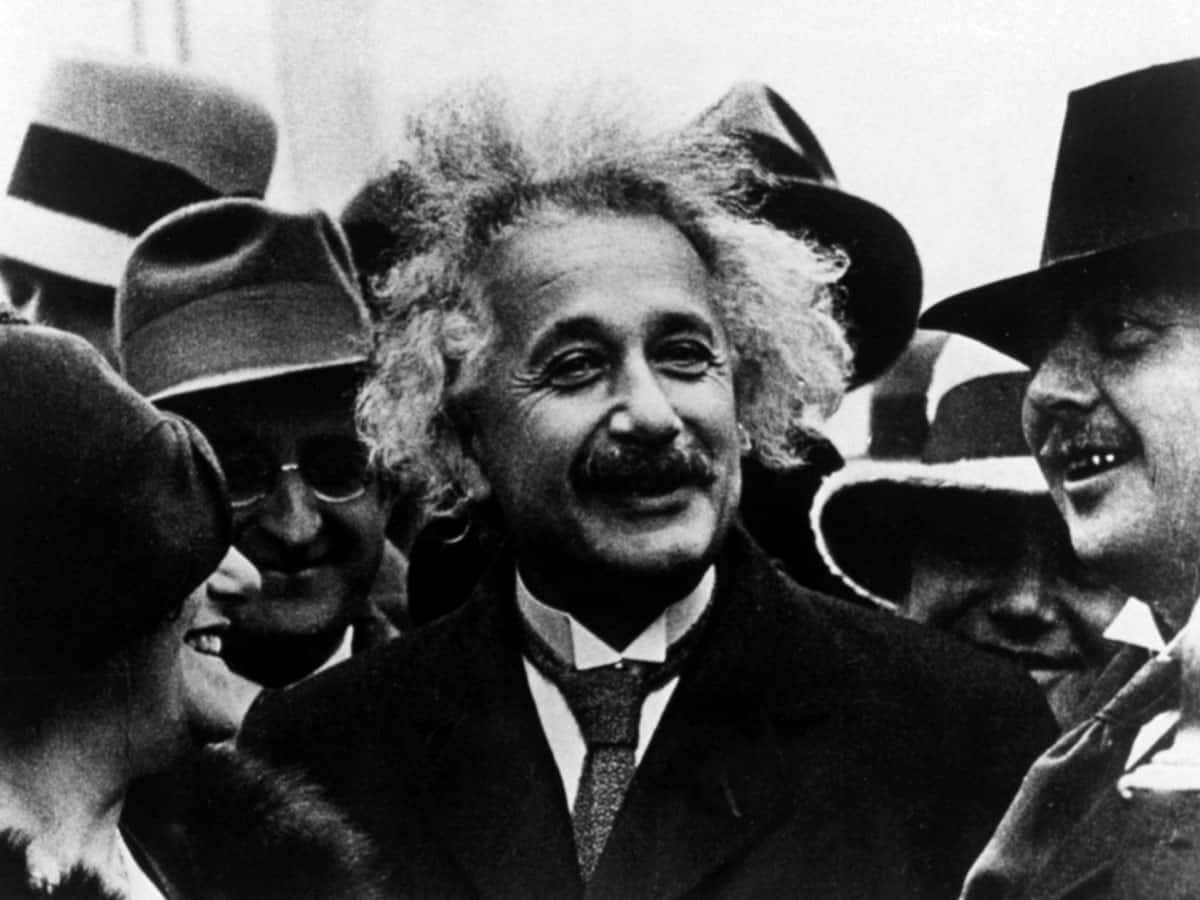

It is difficult to imagine the modern world without the life and work of Albert Einstein. Not only is he one of the most quoted figures of the 20th century, he is also one of the most quoted people who ever lived – on subjects ranging from physics and mathematics to genius, marriage, income tax and peace. “To punish me for my contempt of authority,” he joked in 1930, “fate has made me an authority myself.” By 2015 – the centenary of the publication of Einstein’s general theory of relativity – there existed some 1700 individual books about him, in many different languages, according to a careful count made by Diana Kormos Buchwald, the director of the Einstein Papers Project at the California Institute of Technology.

This figure – which is far ahead of that for any other scientist – is now probably closer to 1750 books, judging from the number of recent Einstein titles published. In this review I look at four of these – No Shadow of a Doubt by Daniel Kennefick; Einstein’s War by Matthew Stanley; Proving Einstein Right by S James Gates Jr and Cathie Pelletier; and Einstein’s Wife by Allen Esterson and David C Cassidy with contribution by Ruth Lewin Sime. This selection ranges from the highly abstract concepts of relativity to the deeply personal conflicts between Einstein and his first wife, Mileva Marić. And yet, a century ago, in 1919, no-one had even heard of Einstein except for his family, a handful of friends mainly in Germany, and a select group of physicists and mathematicians, many of whom distrusted both special and general relativity.

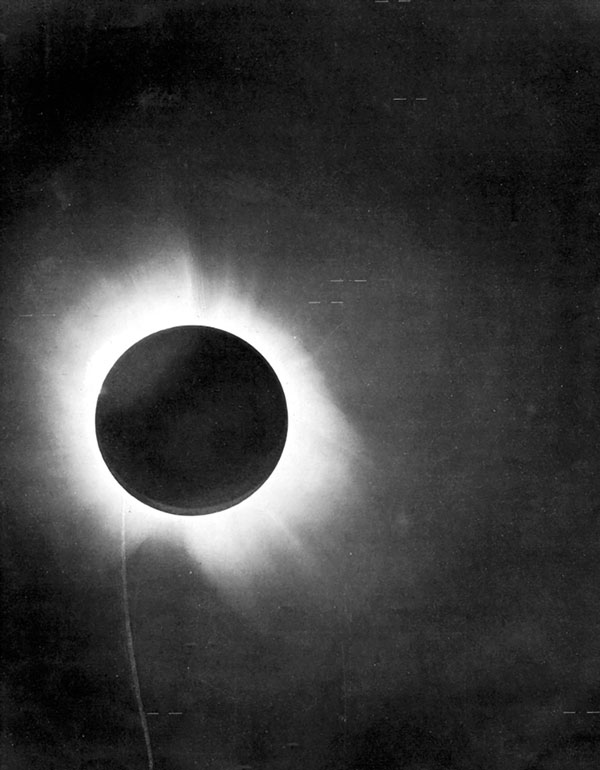

His fame began in November 1919, after a historic meeting of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society in London. Arthur Eddington, the Plumian Professor of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge, and Frank Dyson, the Astronomer Royal, announced that their observations of a solar eclipse on 29 May from west Africa (Príncipe) and north-eastern Brazil (Sobral) had confirmed – almost for sure, but still with a margin of uncertainty – a key prediction of Einstein’s controversial theory of 1915. Light from distant stars passing the Sun, on its way to the Earth, is deflected by solar gravity through a particular angle, 1.75 arcseconds – twice the angle predicted by Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity.

Warring views

Almost immediately, Einstein was celebrated on both sides of the Atlantic. When he first visited the US in 1921, New Yorkers lined the streets to cheer his appearance in a motorcade. When he travelled to Britain for the first time, just after his US visit, and gave a lecture in German on relativity at King’s College in London, there was also an overflowing audience. In London, however, they kept silent when Einstein mounted the platform, and refused to applaud him. Only later, after Einstein’s lecture had won them over with tact and charm, came a storm of encouraging applause. Why such an astonishing disparity in Einstein’s British and American receptions? The reason was the First World War. Well after the end of this terrible struggle in 1918, anti-German feeling still ran high in Britain, unlike in the US.

Einstein in Oxford

Einstein had published his general theory of relativity in wartime Germany in 1915–1916. As a Swiss citizen, and a self-proclaimed pacifist, he had managed to avoid any work for the military, unlike his German scientific colleagues, such as Fritz Haber. Eddington, almost alone in Britain, embraced Einstein’s theory and published a version of it in English in 1918. Eddington too was a pacifist; a Quaker conscientious objector who nearly went to jail. He remained free only with the support of Dyson, who was determined that Eddington should lead the 1919 eclipse observations. Eddington argued with fellow British scientists, and was against demonizing German scientific colleagues both during and after the war. Post-war Britain still formally excluded German scientists from conferences. In early 1920 the Royal Astronomical Society even withdrew its recommendation of a Gold Medal for Einstein – to the embarrassment of Eddington – because of nationalist feeling among the society’s fellows, who viewed Einstein as German, not as Swiss.

Relativity’s complex relationship with the world war is the subject of three significant new books

Relativity’s complex relationship with the First World War, plus the story of solar eclipse expeditions – before, during and after the war – are the subject of three significant books published during the centenary of the 1919 observations. No Shadow of a Doubt, by physicist and Einstein scholar Kennefick, is a thorough study intended more for academics than general readers, with far more technical detail on the eclipse observations than Einstein’s War by historian of science and Eddington scholar Stanley. His book is aimed more at a general readership than Kennefick’s, thanks to his skilful interweaving of the lives of Einstein and Eddington into a readable narrative.

Getting personal

By contrast, Proving Einstein Right, by physicist Gates and novelist Pelletier, is deliberately light on physics but vivid on human drama, including Einstein’s painful divorce of 1919 and Eddington’s challenging working conditions in Africa. Using both familiar and newly researched material, Gates and Pelletier tell the personal stories of not only Einstein and Eddington, but also a wide variety of less-familiar scientists, such as the German astronomer Erwin Finlay-Freundlich and the American astronomer William Wallace Campbell. They were involved with solar-eclipse expeditions in the decade between 1911, when Einstein first proposed the deflection of light by gravity (but agreed with Newton’s value), and 1922, when Campbell’s eclipse observations in Australia finally settled beyond any doubt that the deflection conformed with Einstein’s prediction of 1915–1916 (twice that of Newton).

Arguing about Einstein’s wife

The fourth book, Einstein’s Wife – by Cassidy, a historian of science, and mathematician Esterson, with a brief essay on “Women in science” by Sime, biographer of Lise Meitner – contains little physics and nothing about the eclipse of 1919. It focuses, instead, on the personalities of Einstein and his first wife. Its purpose is to establish, as far as possible from the limited documentary evidence available, whether Mileva Marić contributed substantially to Einstein’s physics. This is something that has been controversially claimed by certain writers since the first sensational publication, in the 1980s, of Einstein’s correspondence with his wife. After a well-argued, exhaustive (and frankly exhausting) dissection of the claims, the book’s answer is that she did not. It is hard to disagree, especially given the unquestioned facts that Marić herself never made this claim and her letters to Einstein do not discuss physics – not to mention that Einstein’s creation of general relativity in 1915–1916 (after his separation from Marić in 1914) was a famously solitary achievement.

Inevitably, both Kennefick and Stanley cover similar scientific material. Their interpretations of the eclipse observations are broadly comparable. However, they differ significantly about the influence of the First World War on the reception of the observations. In Stanley’s view, during the world war Einstein had to fight a private “war” on behalf of his theory – with sceptics who believed in Newton’s absolute space and time, and the long-established concept of the ether, in which light could not be deflected by gravity. “Einstein’s personal war was not unlike the Western front. It had been in a stalemate for some time,” observes Stanley. “Relativity’s sudden explosion, and Eddington’s zealous evangelism for it, would never have happened in quieter times,” he argues. “The theory had few applications for decades and, even if it had been confirmed, would likely have languished in dusty journals until cosmologists or GPS engineers realized they needed its delicate adjustments. Without the war, relativity would have been just one more theory, true but obscure; without the war, Einstein just one more name for bored schoolchildren to memorize.” He concludes: “If Eddington had not cared about pacifism, we would not have had the relativity revolution in 1919.”

Kennefick, by contrast, writes that: “I find it difficult to believe that Eddington’s experience of being a pacifist during the war led him to expect public approbation for his efforts.” The vital ingredient in Eddington’s success was instead his scientific background: both theoretical and practical. “He was a theorist with the right mathematical training who worked on the topic of celestial mechanics, which was suffering from the incompatibility of gravitational law with relativity theory. In addition, he had done extensive work in astrometry, the skill required for actually carrying out the observational test. It is true that Eddington and Einstein shared pacifist ideals and internationalist sentiment, but their common scientific interests are what brought them together.”

Einstein, the travelling physicist

Both books deal with the long-running allegations by contemporary and later scientists against the expedition astronomers (Eddington in particular) that their results were not as conclusive evidence for general relativity as they claimed. It is alleged that, essentially, Eddington claimed more precision for the observations than was technically possible with the telescopes available in 1919, fudging the data because he was theoretically biased in favour of Einstein’s relativity. For example, Stephen Hawking comments in A Brief History of Time: “This proof of a German theory by British scientists was hailed as a great act of reconciliation between the two countries after the war. It is ironic, therefore, that later examination of the photographs taken on that expedition showed the errors were as great as the effect they were trying to measure. Their measurement had been sheer luck, or a case of knowing the result they wanted to get, not an uncommon occurrence in science.”

Sceptical convert

While the evidence of the photographic plates is complicated, it seems to acquit Eddington of fudging, if not of bias. In addition, a relevant aspect of the expeditions has been underestimated, even though it is beyond dispute, as explained by Kennefick. In a nutshell, Dyson’s role was as important as Eddington’s. First, Dyson – who launched the expedition project in 1917 with money from the British government – was a long-time sceptic about relativity.

In December 1919, soon after the great announcement in London, he wrote to another astronomer, George Ellery Hale of the Mount Wilson Observatory in California: “I was myself a sceptic, and expected a different result. Now I am trying to understand the principle of relativity and am gradually getting to think I do.” Only in 1922, following the American eclipse observations in Australia, did Dyson declare: “I don’t think there is ‘any possible shadow of doubt’ about the correctness of Einstein’s prediction of the deflection of light, whatever difficulties may be found with the rest of his theory.”

Second, and even more important, Dyson, not Eddington, carried out the analysis of the data from Sobral, which actually confirmed Einstein’s prediction – the data from Príncipe, obtained by Eddington, were too meagre for definite conclusions as a result of cloudy weather obscuring the Sun. According to Kennefick, “We can conclude the Sobral data reduction was conducted independently of Eddington. The initials on the data sheets; the fact that the reduction was undoubtedly performed at Greenwich and not at Cambridge, where Eddington was; and the fact that Dyson was solely responsible for discussing the Sobral data in his written report all reinforce this impression.”

Space, time and spooky action

That said, the severely limited data raise a fascinating question. How did Einstein come up with his theory in 1915? He developed it from a very narrow empirical base, relying primarily on his scientific imagination, notes Kennefick. But it has passed every subsequent test for more than a century, most recently its prediction of gravitational waves and black holes.

When Einstein himself lectured on “The origin of the general theory of relativity” at the University of Glasgow in 1933, he disarmingly confessed: “In the light of the knowledge attained, the happy achievement seems almost a matter of course, and any intelligent student can grasp it without too much trouble. But the years of anxious searching in the dark, with their intense longing, their alternations of confidence and exhaustion and the final emergence into the light – only those who have experienced it can understand that.”

- No Shadow of a Doubt: the 1919 Eclipse That Confirmed Einstein’s Theory of Relativity by Daniel Kennefick, 2019 Princeton University Press 413pp

- Einstein’s War: How Relativity Triumphed Amid the Vicious Nationalism of World War I by Matthew Stanley, 2019 Dutton 400pp

- Proving Einstein Right: the Daring Expeditions That Changed How We Look at the Universe by S James Gates Jr and Cathie Pelletier, 2019 PublicAffairs 368pp

- Einstein’s Wife: the Real Story of Mileva Einstein-Marić by Allen Esterson and David C Cassidy, with contribution by Ruth Lewin Sime, 2019 MIT Press 336pp