By Margaret Harris in Daejeon, Republic of Korea

For almost three years, the HANARO research reactor has been idle. Built in 1995 as a hub for neutron-scattering experiments, radioisotope production and other scientific work, HANARO (High Flux Advanced Neutron Application Reactor) is the only facility of its kind in the Republic of Korea, and it underwent a major upgrade in 2009. Then, in 2014, the facility became a delayed casualty of the meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power station, as enhanced regulatory scrutiny led to the discovery that the reactor hall’s outer wall was not up to the latest standards. An enforced shutdown followed while the wall was reinforced, and although the works were supposed to take just 18 months, opposition from local citizens’ groups has led to further delays.

So when will HANARO reopen? Chang-Hee Lee, director of neutron science research at the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI), offered an ambiguous answer earlier today in his talk at the 11th International Conference on Neutron Scattering (ICNS) in Daejeon. “Soon,” he declared, to murmurs of sympathy from the audience. “How soon? We hope two months. But it could be the end of the year.”

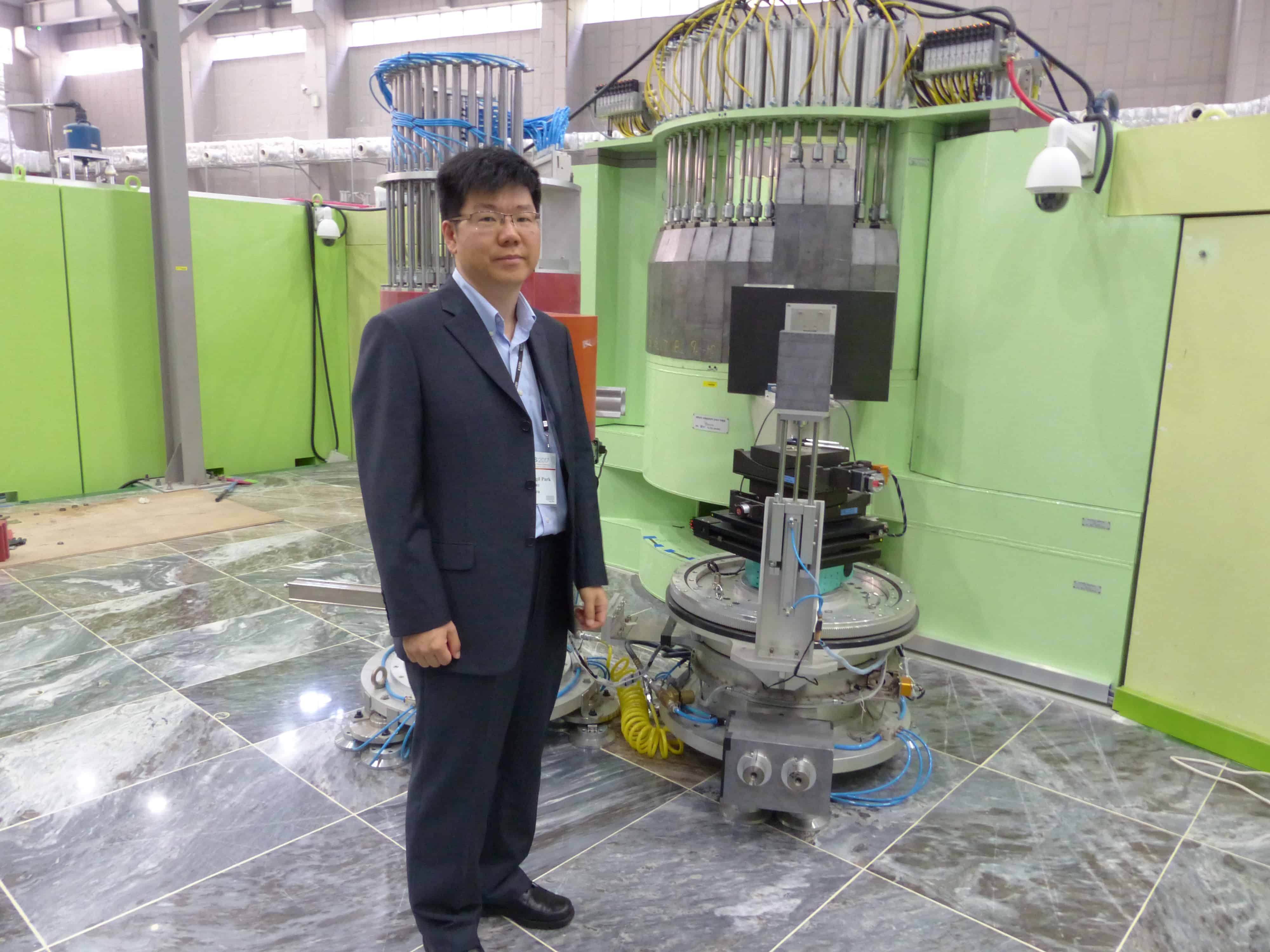

The physicists at KAERI clearly would have preferred to show off a working facility to the scientists gathered for the ICNS, which takes place every four years. And as KAERI instrument scientist Sungil Park drove me to the reactor for a tour, it struck me that the reason for the extended delay must be frustrating, too: HANARO’s location halfway up a hill and some 50 km inland surely puts it at low risk of a Fukushima-style tsunami.

When I asked Park about the citizens’ concerns, he was diplomatic in his reply, noting that Korea was hit by a magnitude 5.8 earthquake last year and that Daejeon’s expansion means that the area around HANARO is more heavily populated than it once was. And in any case, scientists have not been idle. As Park explained as we walked around the facility’s guide hall, he and his colleagues have used the closure to update their suite of instruments. These include Park’s own project – a cold neutron triple-axis spectrometer that will be used to study phonons and other collective excitations in condensed-matter systems – a neutron radiography facility and two small-angle neutron-scattering instruments.

In the conference’s opening ceremony, KAERI principal researcher Jaejoo Ha devoted part of his speech to HANARO’s status. “For a long time, scientists in Korea had to put up with a low-power source and mediocre instruments,” he said, referring to the days before HANARO replaced an older 2 MW reactor. A lot of work would be required to get everything back up and running, he added. But after thanking attendees for giving Korean scientists beamtime at their own national facilities, he ended on a positive note: “I promise to return the favour when our reactor is working again.”