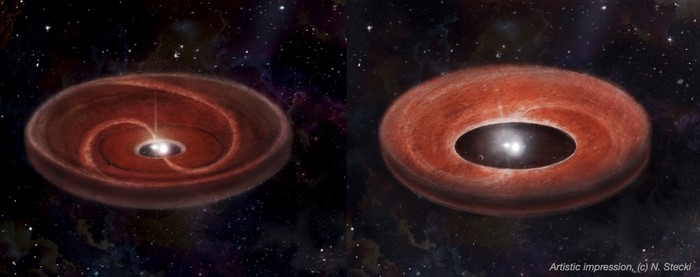

Even as they are dying, ancient stars in some binary systems may be forming planets, an international team of astronomers has found. Through infrared observations of old binary pairs, researchers led by Jacques Kluska at KU Leuven in Belgium discovered 10 cases in which giant planets have likely carved out empty cavities in protoplanetary discs. If more evidence is found for such systems, it could result in a rethink of current ideas about how planets form.

By observing the huge protoplanetary discs of gas and dust surrounding nascent stars, astronomers have developed a good understanding of how planets form. The process begins with matter in the disc clumping together to eventually form dense regions, which carve out distinctive, ring-shaped cavities in the disc. This process gives rise to fully formed planets just a few million years after the formation of the host stars.

However, protoplanetary discs have also been discovered in some ancient binary systems that contain a white dwarf. These stars have blasted away much of their atmospheres, which then surrounds the binary system. The gravitational interplay between the two stars can then cause the ejected matter to form a “second generation” protoplanetary disc in which planets could form.

Infrared emissions

To look for signs of planet formation in these second-generation systems, Kluska’s team focused on infrared emissions from discs. Previous studies of young protoplanetary discs suggest that infrared emissions decline as planets carve out cavities.

The astronomers analysed the emissions of 85 ancient binary systems in the Milky Way. They discovered that 10 of these binaries have a disc emitting lower levels of infrared light. This provides promising evidence that giant planets have begun to form around these dying stars.

Compositions of exoplanets and their stars have a surprising relationship, study reveals

In addition, they discovered that the surfaces of the dying white dwarfs in these systems had low levels of stable refractory metals – which have very high melting and boiling points. This suggests that dust particles rich in heavy refractory elements have been captured by newly forming planets, rather than falling back onto the star.

In their future research, Kluska and colleagues aim to directly observe planet formation in these 10 systems using the powerful telescopes available at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile. If successful, these protoplanetary discs will provide a unique opportunity for studying second-generation planet formation.

The research is described in Astronomy and Astrophysics.