Astrophysicists in Germany and North America have published plans to build the world’s largest neutrino telescope on the sea floor off the coast of Canada. The Pacific Ocean Neutrino Experiment (P-ONE) is designed to snare very-high-energy neutrinos generated by extreme events from beyond our galaxy.

Neutrino telescopes observe the Cerenkov radiation that is emitted when neutrinos passing through the Earth interact very occasionally with atomic nuclei resulting in the production of fast-moving secondary particles. Being uncharged and exceptionally inert, neutrinos can penetrate gas and dust as they travel through the universe, allowing astronomers in principle to identify the exceptionally energetic phenomena that generate them. Photons from such events, in contrast, are absorbed on their journey.

We are now on the verge of opening up neutrino astronomy

Elisa Resconi

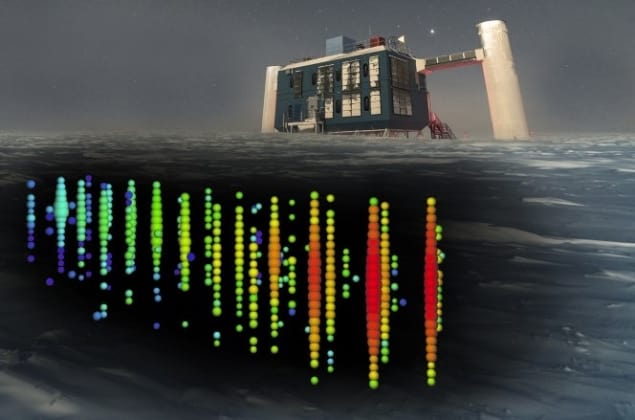

The world’s largest neutrino telescope, known as IceCube, consists of dozens of strings of photomultiplier tubes suspended in holes drilled deep into the ice at the South Pole. Covering a volume of 1 km3, IceCube made history in 2013 when it reported intercepting the first extragalactic neutrinos. Four years later it then recorded an event that could be tied to a very distant, bright galactic nucleus known as a blazar, thanks to concurrent gamma-ray observations.

According to P-ONE head, Elisa Resconi at the University of Munich, IceCube’s 2017 result strictly speaking only constitutes “evidence” for the blazar source. To really claim a discovery and pinpoint the origin of other cosmic neutrinos, she argues, requires the construction of additional neutrino observatories as well as the extension of IceCube. “We are now on the verge of opening up neutrino astronomy,” she says, “but if we base this process on just one telescope it could take a really long time, perhaps decades.”

Heading underwater

P-ONE will consist of seven groups of 10 detector strings creating an instrument volume of about 3 km3. Being larger than IceCube, it will detect rarer, higher-energy neutrinos, and will be most sensitive at a few tens rather than a handful of teraelectronvolts. It will also observe a different part of the sky, mainly capturing neutrinos from the southern hemisphere rather than the north. But there will be some overlap between the two, says Resconi, potentially allowing independent observations of the same event.

The new facility will be located at a depth of about 2.6 km in the Cascadia Basin, some 200 km from the coast of British Columbia. As such, it will take advantage of pre-existing infrastructure – an 800 km-long loop of fibre-optic cable operated by the University of Victoria’s Ocean Networks Canada that supplies power and ferries data to and from existing sea-floor instruments.

Having already confirmed that this site has the necessary optical properties by sending down two initial strings of light emitters and sensors in 2018, the P-ONE collaboration are now planning to deploy a steel cable with additional detectors to investigate the site – including spectrometers, lidars and a muon detector. The plan then, says Resconi, is to install the first part of the observatory – a ring containing seven 1 km-long strings – around the end of 2023. And if that succeeds, the researchers will then apply for the bulk of the $50–100m needed to complete the project, with personnel costs adding roughly $100m more.

Resconi hopes that the full observatory will be installed and taking data by the end of the decade. But she describes this timeline as “very ambitious”. In addition to delays caused by the ongoing COVID- 19 pandemic, she says it will be a challenge to ensure that the detectors work as planned – given the huge pressures and the presence of salt and sea creatures, which together make the seabed such a harsh environment. Looking at the sky from under water

Indeed, scientists had already planned on operating a cubic-kilometre scale neutrino telescope known as KM3NeT on the floor of the Mediterranean Sea back in 2014, which was delayed to 2020. According to collaboration member Feifei Huang, just two of the 230 strings due to be installed off the coast of southern Italy are so far in place, while another site in French waters currently has six out of a planned 115 strings running – with completion not foreseen until 2026 and 2024 respectively.

Resconi says that part of the problem with that project is a lack of specialist personnel, with the physicists essentially doing everything themselves – for example, their self-built junction boxes, which connect cables on the sea floor, having failed. She hopes that the experience acquired by Ocean Networks Canada will mean a similar fate can be avoided for P-ONE. With 30 or 40 people dedicated to laying cables in the ocean, she says that her team “can focus on the physics”.