Atoms in a one-dimensional quantum gas behave like a Newton’s cradle toy, transferring energy from atom to atom without dissipation. Developed by researchers at the TU Wien, Austria, this quantum fluid of ultracold, confined rubidium atoms can be used to simulate more complex solid-state systems. By measuring transport quantities within this “perfect” atomic system, the team hope to obtain a deeper understanding of how transport phenomena and thermodynamics behave at the quantum level.

Physical systems transport energy, charge and mass in various ways. Electrical currents streaming along a wire, heat flowing through a solid and light travelling down an optical fibre are just three examples. How easily these quantities move inside a material depends on the resistance they experience, with collisions and friction slowing them down and making them fade away. This level of resistance largely determines whether the material is classed as an insulator, a conductor or a superconductor.

The mechanisms behind such transport fall into two main categories. The first is ballistic transport, which features linear movement without loss, like a bullet travelling in a straight line. The second is diffusive transport, where the quantity is subject to many random collisions. A good example is heat conduction, where the heat moves through a material gradually, travelling in many directions at once.

Breaking the rules

Most systems are strongly affected by diffusion, which makes it surprising that the TU Wien researchers could build an atomic system where mass and energy flowed freely without it. According to study leader Frederik Møller, the key to this unusual behaviour is the magnetic and optical fields that keep the rubidium atoms confined to one dimension, “freezing out” interactions in the atoms’ two transverse directions.

Because the atoms can only move along a single direction, Møller explains, they transfer momentum perfectly, without scattering their energy as would be the case in normal matter. Consequently, the 1D atomic system does not thermalize despite being subject to thousands of collisions.

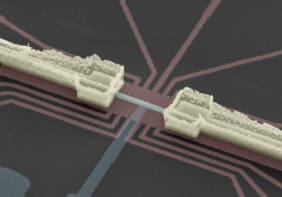

To quantify the transport of mass (charge) and energy within this system, the researchers measured quantities known as Drude weights, which are fundamental parameters that describe ballistic, dissipationless transport in solid-state environments. According to these measurements, the single-dimensional interacting bosonic atoms do indeed demonstrate perfect dissipationless transport. The results also agree with the generalized hydrodynamics (GHD) theoretical framework, which describes the large-scale, inhomogeneous dynamics of one-dimensional integrable quantum many-body systems such as ultracold atomic gases or specific spin chains.

A Newton’s cradle for atoms

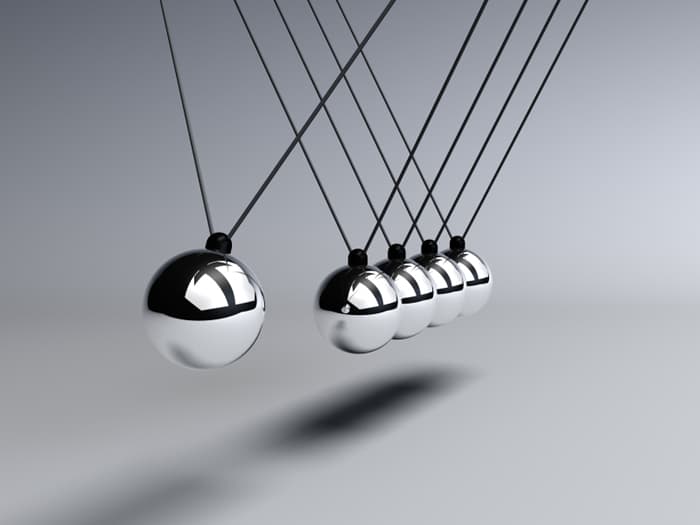

According to team leader Jörg Schmiedmayer, the experiment is analogous to a Newton’s cradle toy, which consists of a row of metal balls suspended on wires (see below). When the ball on one end of the row is made to collide with the one next to it, its momentum transfers straight through the other balls to the ball on the opposite end, which swings out. Schmiedmayer adds that the system makes it possible to study transport under perfectly controlled conditions and could open new ways of understanding how resistance emerges, or disappears, at the quantum level. “Our next steps are applying the method to strongly correlated transport and to transport in a topological fluid,” he tells Physics World.

Karèn Kheruntsyan, a theoretical physicist at the University of Queensland, Australia, who was not involved in this research, calls it “a significant step for studying quantum transport”. He says the team’s work clearly demonstrates ballistic (dissipationless) transport at a finite temperature, providing an experimental benchmark for theories of integrability and disorder. The work also validates the thermodynamic meaning of Drude weights, while confirming that linear-response theory and GHD accurately describe transport in quantum systems.

How to build a quantum Newton’s cradle

In Kheruntsyan’s view, though, the team’s biggest achievement is the quantitative extraction of Drude weights that characterize atomic and energy currents, with “excellent agreement” between experiment and theory. This, he says, shows truly ballistic transport in an interacting many-body system. One caveat, though, is that the system’s limited spatial resolution and near-ideal integrability prevent it from being used to explore diffusive regimes or stronger interaction effects, leaving microscopic dynamics such as dispersive shock waves unresolved.

The study is published in Science.