Some business models might seem crazy. But they’re not mad if they work, as James McKenzie explains

My friends and I were talking the other day about the craziest thing we’d seen over the last few years, discounting politics that is.

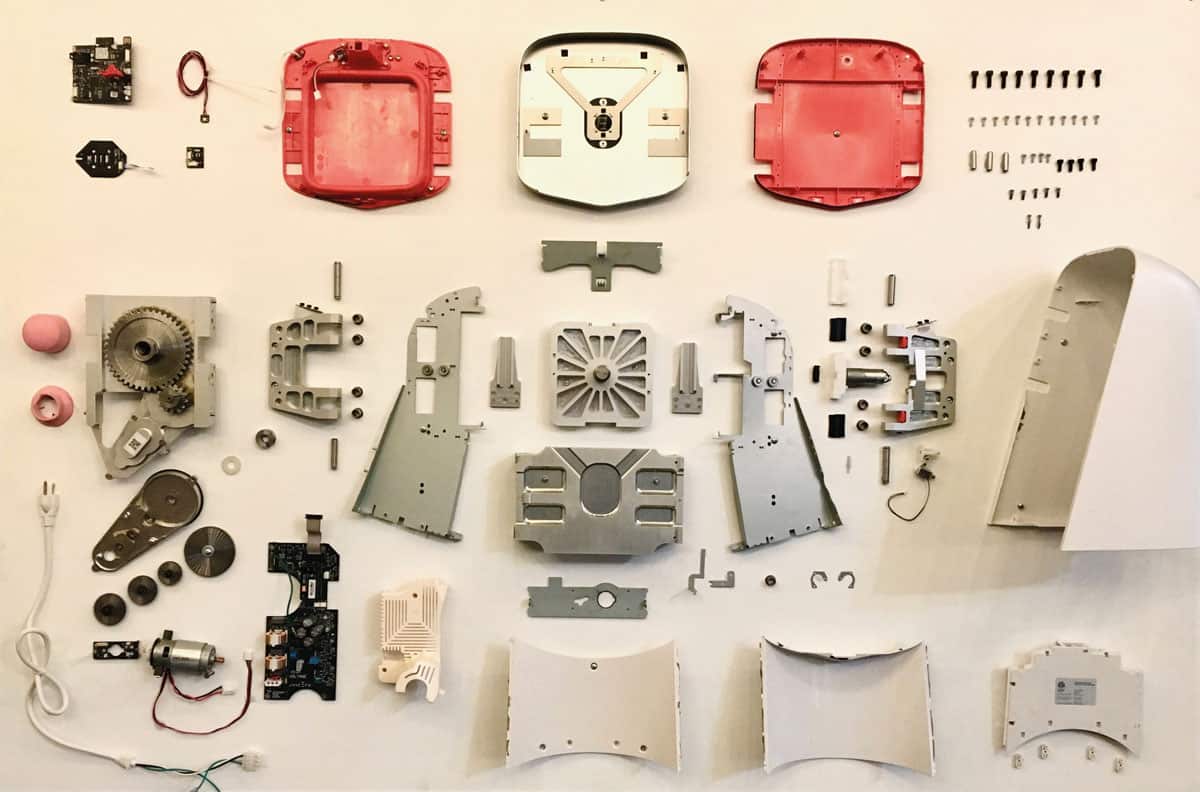

We began with Juicero – a $399 WiFi-connected juicer, billed by the company’s founder Doug Evans as “the first at-home cold-pressed juicing system”. Launched in 2016, the Juicero promised a glass of fresh juice every morning without you having to squeeze fruit with your bare hands. The firm, based in California, had received $120m in venture-capital funding from serious investors including Google’s parent firm Alphabet Inc. The Juicero was such a beautiful product that Apple, if they’d been in the juice market, would have been proud of it.

As a business model, a WiFi-connected juicer appealed to investors, offering health and lifestyle benefits for cash-rich, time-poor Silicon Valley hipsters, while guaranteeing a recurring revenue to the company through sales of its bags. All customers had to do was buy a machine, register the device, download an app to their phone, order a $5–7 “produce pack”, wait for it to arrive, scan a QR code and ensure their Internet-connected device had checked “the quality of the product”.

Then someone at Bloomberg squeezed a Juicero bag by hand and made a drink just as well as the fancy WiFi-connected device – all for a fraction of the price. Almost overnight the product was scorned as a symbol of Silicon Valley hubris and the answer to a question everyone realized that maybe, sort of, they hadn’t actually been asking. Undeterred, other firms tried to copy their device, with Juicero filing a complaint in federal court in April 2017 against a competing cold-press juicing device, the Froothie Juisir, for allegedly infringing its patent.

Sadly, the Juicero turned out to be one of the most amazing business flops of recent times

Sadly, the Juicero turned out to be one of the most amazing business flops of recent times. On 1 September 2017 the company announced it was suspending sales of the juicer and the packets. The business model (equipment + consumables + subscription) was not inherently crazy. After all, parts of this approach have been used to sell everything from coffee machines to razor blades. But applied to juice, which you can just as easily buy in the supermarket, it was way too complex and expensive.

Fruity flop

The key questions for any business are simple. What problem are you trying to solve for the customer? And is your solution the simplest and most cost-effective way of delivering that value proposition with the least effort for the customer? Subscription models can work extremely well of course – just look at the success of Netflix, Amazon Prime and Sky. But they have better thought-out value propositions and pricing than Juicero. Spending $5–7 on a single juice is silly when you could spend that amount of money on fruit and veg from your local store and make oodles of drinks using a plastic squeezer – or just buy it ready made.

The Juicero is part of the “delivery-on-demand” trend made possible thanks to our online connected world. Scan the website of any Silicon Valley venture capital firm and you’ll find all sorts of startups innovating and occasionally reinventing the stuff you used to take for granted. One I do like is Feather – a service that lets you “subscribe” to your furniture. On the face of it, subscribing to a settee or lamp sounds crazy. But it works as a business and is ideal for people renting houses and flats in cities. Customers get to pick the latest fashions and have their furniture delivered. Plus, you can change your furniture if you get bored and it gets taken away when you move – all for just $19 per month. Sounds a “no-brainer” doesn’t it?

Health check

While talking with my friends, Theranos also came up in conversation. It’s a private health-technology firm founded in 2003 by Elizabeth Holmes, a 19-year-old Californian who modelled herself on Steve Jobs (including wearing black polo necks). Her company, which claimed it had revolutionized blood tests using only a fingerprick of the stuff, raised more than $700m from venture capitalists and private backers. Investors and the media hyped Theranos as a breakthrough product in the US diagnostic-lab market, which is worth more than $70bn a year. At its peak, the firm was valued at $10bn.

The turning point came in October 2015, when John Carreyrou, an investigative reporter from the Wall Street Journal, questioned the validity of Theranos’ technology.

The turning point came in October 2015, when John Carreyrou, an investigative reporter from the Wall Street Journal, questioned the validity of Theranos’ technology, leading to a string of legal and commercial challenges. Then, on 14 March 2018 Theranos, Holmes and former company president Ramesh Balwani were charged with fraud by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC said Holmes had made many false claims including one in 2014 that her company had annual revenues of $100m, when the actual figure was barely $100,000.

Despite those problems, I believe that Theranos had a great business model. If the technology actually existed to deliver its claims, the firm would be on to a winner. Imagine being able to diagnose hundreds of health issues on the spot in your local supermarket or pharmacy with a simple prick-of-the-finger blood test. Mind you, the firm won’t be going out of the spotlight: apparently it’s going to be turned into a Hollywood movie called Bad Blood with Jennifer Lawrence in the starring role.

So Theranos didn’t work out. Fraud is a bad business model. But plenty of firms with mad business plans do succeed. And that’s the point: no matter how crazy a business plan sounds, if it works out commercially, it’s not crazy at all.