Tasneem Zehra Husain’s imaginative physics-history novel Only the Longest Threads and Peter Adey’s ramble through Air: Nature and Culture, reviewed by Margaret Harris

Tangled threads

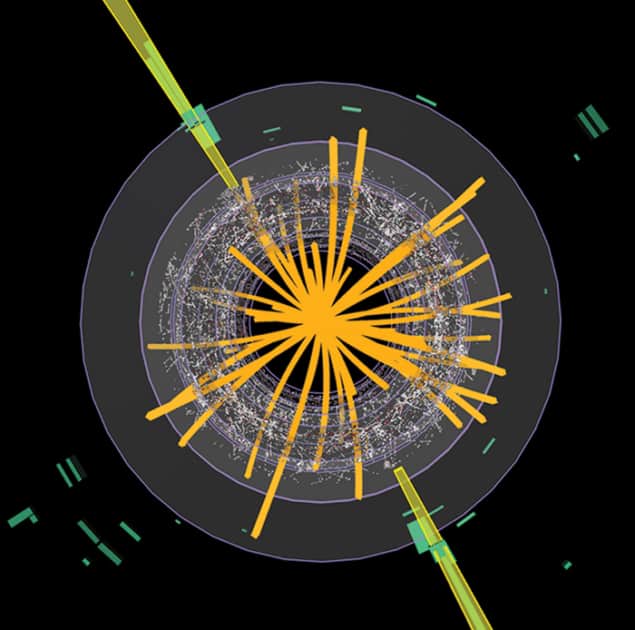

In the opening scenes of Tasneem Zehra Husain’s novel-cum-physics history Only the Longest Threads, a string theorist called Sara and a struggling science writer called Leo meet at CERN on the day the discovery of the Higgs boson is announced. Drawn together by their passion for physics (plus a dash of love-at-almost-first sight), Sara becomes Leo’s muse, urging him to break his journalistic detachment and write about physics through the medium of fiction. The rest of Husain’s novel consists of chapters from Leo’s book (each of which is written from the viewpoint of a fictional witness to an important moment in physics history), interspersed with e-mails between Leo and Sara in which they gush about how amazing it all is. In summary, then, Only the Longest Threads is a book written by a real string theorist and author (Husain), in which a fictional string theorist (Sara) and a fictional author (Leo) write a fictional book about fictional people’s perspectives on real physics. It is all rather laboured, and terribly meta, which is a shame because underneath this clunking exoskeleton is a fine piece of science writing. Husain explains physics concepts well, in strong, imaginative prose, and by describing historical breakthroughs through the eyes of (fictional) contemporaries, she captures the sense of wonder that these discoveries evoked at the time. The first chapter of “Leo’s” book, for example, is written from the perspective of an 18th-century English schoolboy who is reading Newton’s Principia Mathematica for the first time, and one gets an almost palpable sense of how Newton’s science must have seemed like a shaft of light through the darkness. It’s thrilling stuff, and while later chapters do not pack quite the same emotional punch, they do include some excellent, novice-friendly explanations of advanced concepts such as symmetry breaking and what the “gauge” in “gauge theory” is all about. Overall, Only the Longest Threads is a rewarding and thought-provoking read – it’s just a pity that its central premise is too clever by half.

- 2014 Paul Dry Books $16.95pb 219pp

A breath of fresh air

What is air? A chemist might describe it as a mixture of nitrogen, oxygen and a few other chemicals. A physicist might focus instead on its gaseous nature, with particles whizzing around according to the laws of statistical mechanics. A biologist, an artist and a writer might have different perspectives altogether. None of these descriptions is wrong, but all are incomplete. In his book Air: Nature and Culture, Peter Adey attempts to bring all of these viewpoints together. A geographer at Royal Holloway, University of London, Adey has a magpie’s eye for glittering facts. A baby girl born aboard an aeroplane in 1929 was christened “Airlene”. A 17th-century observer described London’s air as “accompanied with a fuliginous and filthy vapour”. Canaries in “Haldane boxes” were used as air-quality detectors in British mines until 1986. And on and on it goes for 200 pages, most of them lavishly illustrated with all manner of paintings, etchings and scientific diagrams. The result is a book that fizzes with ideas, but also, at times, verges on incoherence. One particularly exhausting paragraph refers to the Futurism founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti; the writers T E Lawrence, Thomas Pynchon and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry; the Impressionist painters Claude Monet and Carlo de Fornaro; and “the work of Tullio Crali’s Dogfight” (no other context given), all within a space of barely 200 words. Air also shows signs of inadequate editing: Willard Libby’s work on radiocarbon dating won him the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, not peace, while the pioneers of motion science were called Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, not John and Lillian. That said, for the sake of a phrase like “fuliginous and filthy”, your reviewer is willing to forgive rather a lot. If Air is perhaps a bit less, rather than more, than the sum of its many bright and shining parts, it is still a fascinating book that spins a weird and wonderful story out of the air we breathe.

- 2014 Reaktion Press £14.95hb 232pp