Physics World reviews A Short, Bright Flash by Theresa Levitt and Rocket Girl by George Morgan

A lens that made history

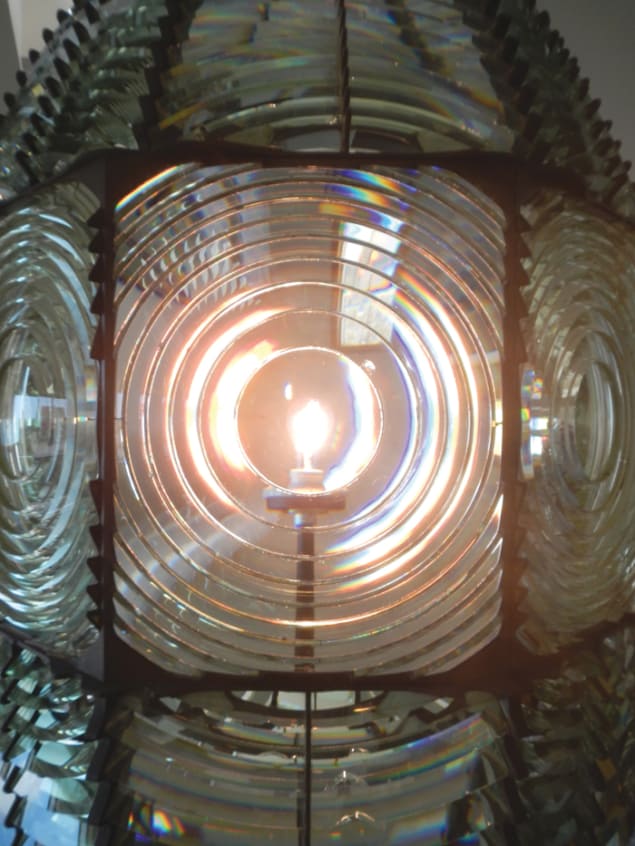

“I have often been annoyed when someone said they’re going to use some sort of thing or another as ‘a lens’ to view history,” writes the science historian Theresa Levitt in the preface to her book A Short, Bright Flash. “Lenses, after all, can do a lot of different things. They can magnify, telescope, invert, diverge, converge and correct, all while inevitably distorting the light that you see.” Her credentials as an optics geek thus established, Levitt goes on to argue that in this case, the phrase is appropriate, since her book really is about a lens, and its development really does reveal something important about history. The subject of A Short, Bright Flash is the Fresnel lens, which was designed by the French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel in the early 19th century and subsequently installed in lighthouses all over the world. Fresnel’s original lens was actually a complex arrangement of prisms that behaved like a single thin, convex lens with a very short focal length. Capable of capturing far more light than its predecessors and collimating it into a single, dazzling beam, the Fresnel lens was a revelation to sailors – but also to scientists, since the equations used to develop it relied on light having a wave-like character, rather than behaving like a particle as Newton had believed. Physicists will enjoy the first part of the book, which is effectively a mini-biography of Fresnel and is packed with interesting titbits about his life and career. Alas, Fresnel died so young that he barely makes it to page 100, and Levitt’s subsequent lengthy digression on the use of Fresnel lenses in US lighthouses will lose many readers from outside that country. The book does pick up again towards the end, when Levitt describes later modifications to Fresnel’s lights, but it never quite matches the short, bright flash of its beginning.

- 2013 W W Norton £14.99/$25.95hb 288pp

A rocketry pioneer’s story

The story of Mary Sherman is a fascinating one. Born to a poor farming family in a remote corner of North Dakota, US, she escaped an abusive childhood by running away to college, where she excelled in science. After her studies were interrupted by poverty, the Second World War and an unplanned pregnancy, she managed to secure a post-war job at a major US defence contractor, where she became the only woman in its 900-strong engineering department. During her relatively brief career, she was instrumental in developing a new type of rocket fuel called hydyne, which made history in January 1958 when it was used to launch the US’s first successful satellite. By then, however, Sherman had already retired to raise her children, and long before her death in 2004, her contributions had been all but forgotten. This is tempting stuff for a biographer, but unfortunately, poor record-keeping, the top-secret nature of Sherman’s work and her own obsessively private disposition made many details of her life difficult or impossible to verify. As a result, George Morgan decided to make his book Rocket Girl a work of “creative nonfiction” rather than a straight biography. It’s a brave decision and probably an essential one if Sherman is to get the credit she deserves. Unfortunately, it also hangs a giant question mark over the book’s accuracy, and for all Morgan’s admirable candour and his doggedness as a researcher, he is ill-placed to dispel it. The reason is that Morgan is Mary Sherman’s son (by her husband and fellow rocket scientist Richard Morgan), and at several points in the book, he reveals himself – perhaps intentionally – as someone with a huge axe to grind concerning his mother’s memory. Less forgivably, Morgan, a playwright at the California Institute of Technology, is also prone to the kind of florid language that made the novelist William Faulkner urge aspiring writers to “kill [their] darlings”. In one especially purple passage, young Mary has not merely fallen pregnant – no, she is “deceived by insincerity, duped by counterfeit promises and impregnated by the sperm cells of deception”. When we meet Morgan’s father for the first time a few chapters later, we are not told that he has red hair; instead, its colour is “a hirsute replication of youthful autumns spent in Vermont”. By comparison, inventing a few non-essential details seems positively virtuous.

- 2013 Prometheus Books $18.00pb 325pp