Books on mathematics and Albert Einstein’s practical side, reviewed by Margaret Harris

On beyond zero

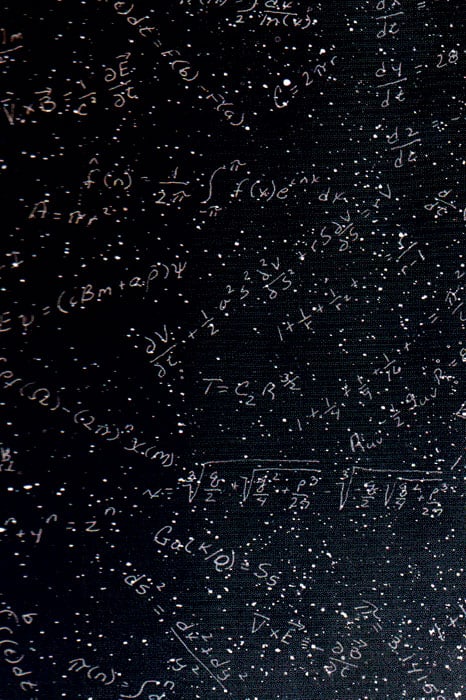

The Universe in Zero Words sounds like the title of a coffee-table book of astronomy photos. The image on its cover – a photograph of the Milky Way – does little to suggest otherwise. But the book Dana Mackenzie has actually written is a very different beast indeed. A closer look at that star-spangled cover reveals a host of equations scattered through the night sky, and inside it is an elegantly illustrated history of mathematical thought, rather than a series of nebula photos. Mackenzie’s chronicle is impressive in its scope, running all the way from 1 + 1 = 2 (an expression with some surprisingly interesting properties) through to 20th-century revelations such as Lorenz’s equations of chaos theory and the realization that some infinities are bigger than others. Understandably, Mackenzie, a mathematician-turned-writer, uses rather more than zero words to describe these discoveries: the book is divided into 24 semi-independent essays, each nominally based on a single equation or group of equations. Most of these expressions will be familiar to physicists, but there are also a few oddities, such as the Chern–Gauss–Bonnet equation, and even “old favourites” such as Maxwell’s equations are often presented with a fresh twist. This tendency is apparent from the first few essays, which frequently give credit to ancient mathematicians who lived outside the Greco-Roman world of Euclid and Archimedes. In particular, an account of Liu Hui, a Chinese mathematician and commentator from the third century AD, enlivens the essay on the “Pythagorean” theorem – which, as Mackenzie makes clear, was not Pythagoras’ invention, having been known to the Babylonians for more than a millennium before Pythagoras started teaching in the 6th century BC. This cross-cultural focus is particularly appropriate given the book’s title, which refers to the Platonist idea that numbers and equations express truths about the universe that are independent of words, language or culture. What was that old proverb about books and covers, again?

- 2012 Princeton University Press £19.95/$27.95hb 224pp

Proof positive

Prove that a parallelogram with equal diagonals must be a rectangle. Show that the surface area of a sphere is exactly two-thirds that of its (closed) cylinder. Derive the equation for a hyperbola. If these instructions induce puzzlement, a vague sense of “I used to know how to do that” or even a barely suppressed twinge of panic, then Measurement deserves a place on your shelf. Written by Paul Lockhart, a New York-based mathematics teacher and education advocate, the book aims not only to teach mathematics, but also to instil in readers a genuine appreciation for the subject and an understanding of why it is beautiful and worth learning. In his introduction, Lockhart admits that this will not be an easy process; mathematics, he writes, is like a jungle, and “the jungle does not give up its secrets easily…I don’t know of any human activity as demanding of one’s imagination, intuition and ingenuity”. On the other hand, mathematics is also “full of enchanting mysteries”, many of which are accessible even to novices – provided they are willing to play around with ideas and also develop a high tolerance for getting stuck. To help readers build their mathematical muscles, Lockhart has peppered his book with questions and puzzles like the ones that opened this review. The solutions to some of them are worked out (or at least worked around) in the text, but most are left as an exercise for the reader, without further comment or explanation from Lockhart. In a formal textbook, such an approach would be frustrating – especially for students with problem sets due every week, who seldom have the luxury of letting it “take hours or even days for a new idea to sink in”, as Lockhart advises. In the more relaxed and playful context of Measurement, however, it seems to work, and readers who try some of the easier puzzles will soon find themselves ready for more challenging fare. And if you do get stuck, Lockhart advises you to start working on another problem, as “it’s much better to have five or six walls to bang your head against” than only one.

- 2012 Harvard University Press £20.00/$29.95hb 416pp

Einstein the inventor

Albert Einstein’s early career as a clerk in the Swiss Patent Office is sometimes perceived as an aberration. Having failed to get a job as a teacher, or to have his true talents properly appreciated by the physics establishment, the story goes that he took this rather boring job only because he needed to eat, or because it allowed him time to construct a gedankenexperiment or two in periods of idleness. There is some truth to this: although Einstein later looked back on the patent office with fondness (calling it “that worldly cloister where I concocted my finest ideas”) he left his job there as soon as he reasonably could, after obtaining an academic post at the University of Zurich. Yet Einstein’s experiences of the patent office never really left him. Even after his theoretical work made him the world’s most famous scientist, he maintained an avid interest in technology and practical inventions. These inventions – along with his musings and expert opinions on other people’s gadgets – are the subject of The Practical Einstein: Experiments, Patents, Inventions by József Illy, a visiting historian at the California Institute of Technology. In this slender book readers will find some fascinating anecdotes about Einstein’s lesser-known scientific results, including a refrigerator he invented with Leó Szilárd and a paper he wrote on the meanderings of rivers. Not all of these efforts were successful. For example, an experiment he conducted on molecular currents in 1915 produced a result that, in Illy’s understated words, “did not stand the test of time”. Similarly, Einstein’s career as an impartial witness for patent disputes – which began after he had moved into academia – was marked by a number of lost cases and bungled court appearances. Even the successful and innovative Einstein–Szilárd refrigerators were preceded by Einstein’s abortive efforts to develop an “ice machine” with his chemist colleague Walther Nernst. The Practical Einstein reads more like a series of stories than a narrative, but Illy does deserve credit for gathering the often incomplete records of Einstein’s practical side into one book.

- 2012 Johns Hopkins University Press £31.50/$60.00hb 216pp