Books about sand, paradoxes in physics and an ill-fated polar expedition, reviewed by Margaret Harris

Playing in the sandbox

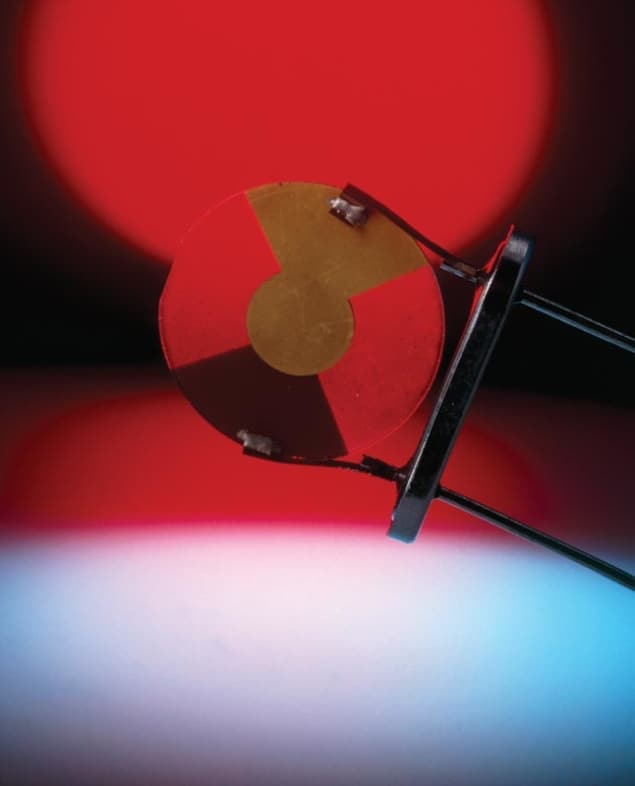

Silicon is the oxygen of human technology. Without it, much of modern civilization as we know it could not exist, since silicon and its compounds – particularly sand and quartz – are found in all manner of electric components and household goods. In Sand and Silicon, the physical chemist Denis McWhan makes an impressive case for the scientific interest of these two related substances, as well as their importance. The book begins with a chapter on piezoelectricity, or the ability of certain types of crystals (including quartz) to become electrically polarized in response to applied pressure. Discovered by Pierre Curie and his older brother Jacques in 1880, piezoelectricity went on to play a major role in the younger Curie’s famous studies of radioactivity. As McWhan describes, piezoelectric crystals lay at the heart of Pierre and Marie Curie’s radiation-detecting apparatus. In the same chapter, the author also delves into the crystal structure of quartz, and shows how piezoelectricity arises from particular types of crystal symmetry. This mixture of theory, applications and history is repeated in later chapters on the crystal architecture of sand, the role of impurities in materials such as semiconductors and the design of photovoltaic solar cells. Written without much mathematics, but with a high level of technical detail, the book would make an excellent introduction for advanced secondary-school students, undergraduates or physicists seeking to fill a gap in their knowledge of materials science.

- 2012 Oxford University Press £29.95/$55.00hb 160pp

Think carefully

Physics is full of apparent paradoxes that, when examined with due care and attention, turn out to make sense after all. This, in a nutshell, is the premise of Paradox: the Nine Greatest Enigmas in Science, the latest book by the British physicist, broadcaster and science communicator Jim Al-Khalili. The book begins with some of the earliest known paradoxes: those of the Greek philosopher Zeno, who in the 5th century BC articulated puzzles concerning arrows in flight and a race between a tortoise and the mythical hero Achilles. After showing how each of Zeno’s paradoxes can be resolved with a little knowledge of kinematics and infinite series – and offering a tantalizing glimpse of a quantum version of Zeno’s Arrow Paradox – Al-Khalili moves on to more recent enigmas. One of these is Olbers’ Paradox, which asks why the night sky appears dark even though there are stars in every direction you look. Fascinatingly, the first person to resolve this paradox seems to have been the American writer Edgar Allen Poe, who intuited in 1848 that the sky is dark because most stars are too far away for their light to have reached us yet. Poe, however, had no proof – a proper resolution to the paradox would not come until 1901, when Lord Kelvin published full calculations – and, as the book’s subsequent chapters illustrate, intuition is seldom a reliable guide in modern physics. (What would Poe have thought about Schrödinger’s cat?) Professional physicists will find few surprises in Al-Khalili’s book, which is aimed more at readers who have never encountered such bread-and-butter physics topics as the Big Bang, special relativity and the second law of thermodynamics. However, Al-Khalili’s explanations of these topics are clear and well written, and the “paradox” concept is an attractive means of grouping them together.

- 2012 Bantam Press £16.99hb 256pp

Into the white abyss

A little over a century ago, a patent clerk with a penchant for physics was preparing to embark on the project that would define his life. His name was Salomon August Andrée (who did you think we were talking about?) and in July 1897, he and two companions set off from the Svalbard archipelago in an attempt to reach the North Pole in a giant silk balloon. They expected the journey to take less than a week and, in retrospect, their optimism seems inexplicable. As Alec Wilkinson notes in his book The Ice Balloon, Andrée’s knowledge of polar wind currents was practically non-existent; his balloon leaked hydrogen from some eight million tiny needle-holes in the fabric; and although the group carried extra provisions in case they had to return by foot or boat, none of them had prepared, mentally or physically, for the sheer effort involved in hauling 300-pound sledges across pack ice. But as Wilkinson explains, the Arctic in the late 19th century was a magnet for scientific dreamers. Moreover, some of these dreamers – including the American Adolphus Greely and the Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen, whose expeditions are described briefly in the book – managed not only to survive, but even to achieve a degree of success. Andrée must have believed himself capable of a similar triumph over adversity. One certainly gets a sense from the book that he was not lacking in confidence. In Wilkinson’s words, Andrée acted as if “moving among disciplines [was] not a matter of broadening oneself…so much as applying one’s customary judgement to new circumstances”. There would be no happy ending for Andrée and his fellow adventurers, but this book about their failure is a moving epitaph for what Wilkinson calls “the heroic age of Arctic exploration”.

- 2012 Knopf $25.95hb 256pp