Books about transits of Venus, scientific tattoos and world-changing equations, reviewed by Margaret Harris

Venus’s moment in the Sun

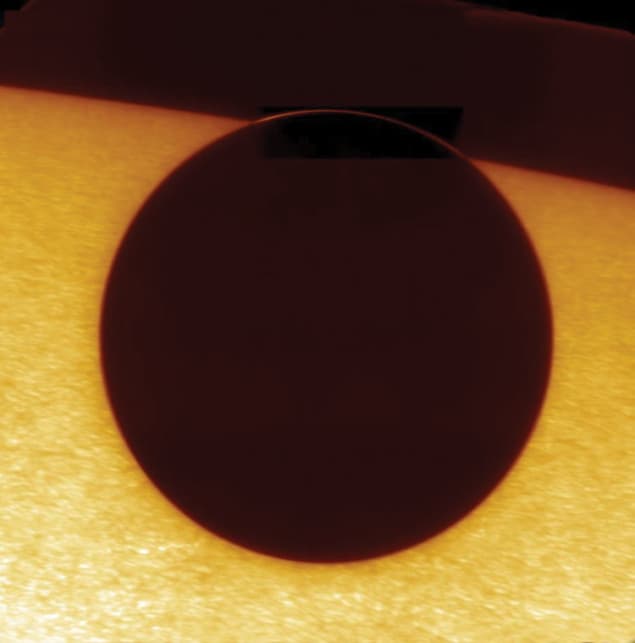

Transits of Venus are like buses: you wait ages for one, then two come along one after the other. Curiously, the same pattern seems to apply to books about the topic, two of which have just been published in the run-up to this year’s transit on 5–6 June (see “Venus: it’s now or never”). Both Mark Anderson’s The Day the World Discovered the Sun and Andrea Wulf’s Chasing Venus focus on the transits that occurred in 1761 and 1769, which were important for two reasons. First, in 1716 Edmond Halley had noted that astronomers could use a transit of Venus to calculate the then-unknown distance between the Earth and the Sun, via the relatively simple expedient of measuring how long the transit lasted when viewed from different places on Earth. Second, by the 1760s, transport networks and telescopes were advanced enough for European scientists to travel to far-flung locations and make decent observations once they got there. As Anderson and Wulf make clear, however, these expeditions were often very near-run things. Many observations were ruined by poor weather or instrumentation, and some of the more intrepid travellers faced astonishing risks during their journeys. Thanks to some excellent source material, both books are packed with suspense and tales of astronomical derring-do. In Wulf’s account, the unlucky French astronomer Le Gentil (who managed to miss both transits, then got stranded on an island on his way home) takes centre stage; Anderson, for his part, is particularly keen on Le Gentil’s fellow-countryman Chappe, whose expedition to a fever-ridden corner of Spanish Mexico proved both successful and fatal. On balance, though, Chasing Venus is the better of the pair, as Wulf leads the reader smoothly through a complex, multi-expedition narrative with a minimum of confusion and a maximum of style.

- 2012 Da Capo Press £17.99/$26.00hb 288pp

- 2012 William Heinemann/Knopf £18.99/$26.95hb 336pp

Getting inked for science

For biophysicist Tristan Ursell, it had to be Euler’s identity, eiπ+ 1 = 0. Climate scientist Andrea Grant preferred Fourier transforms. Nuclear engineer Steven Bigelow went with a radiation trefoil, while Anastasia Gonchar, a chemical physicist, opted for pi orbitals. Welcome to the world of Science Ink, a fascinating and often beautiful collection of science-oriented body art compiled by the US science writer Carl Zimmer. Here, in glorious technicolour, is abundant proof that some people are willing to put up with a lot of pain – not to mention curious stares at the beach or gym – to advertise their devotion to science. Some of the tattoos shown in the book are simple and discreet, like the seismogram of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that adorns the ankle of Julian Lozos, a PhD student in fault dynamics. Others are anything but: one anonymous molecular biologist, for example, chose to have a multicoloured montage of the golden ratio, carbon, glucose, Planck’s constant and the tree of life etched across his chest. At first glance, the book seems like just a bit of fun, but Zimmer’s thoughtfully written text does offer a few interesting messages. One is that the link between a scientific tattoo and a person’s own research is not always straightforward. It is relatively easy to see why an aerospace engineer would want satellites on his arms, but harder to understand why the nitrogen cycle meant so much to a political organizer that he had it drawn across his back. Another intriguing point is that while some people in Zimmer’s book regard their tattoos as a conversation-starter and a tool for scientific communication, others seem motivated by something altogether more primal. In many cultures, Zimmer observes, tattooing is an initiation ritual that symbolizes membership in a tribe. Can it really be a coincidence that so many of the scientists in his book got tattooed to celebrate the end of their PhDs? Zimmer clearly thinks not, but for the sake of the squeamish among us, let’s hope it never becomes a standard part of the viva.

- 2011 Sterling £16.99/$24.95hb 288pp

World-changing maths

For the people who feature in Science Ink, Pythagoras’s theorem, the Schrodinger equation and the square root of minus one are probably all prime candidates for a new scientific tattoo. For University of Warwick mathematician and science writer Ian Stewart, however, they have something else in common: all three of them feature in his latest book, 17 Equations That Changed the World. Strictly speaking, of course, the square root of minus one is not an equation, and if you are the sort of person who objects to that, you should probably avoid this book (several other “equations” are similarly dubious – logarithms, for example, are represented by the expression log xy = log x + log y). Fortunately, the world-changing part of the title is true enough. It would be hard to overestimate the impact of, say, Maxwell’s equations on modern civilization, and although some others among the 17 are less well known (Euler’s formula for polyhedra is a prime example), Stewart’s lively essays on their origins, development and applications make a good case for their inclusion.

- 2012 Profile Books £15.99pb 352pp