On Yuri Gagarin, Marie and Pierre Curie, and the shooting of John F Kennedy

Charting the first man in space

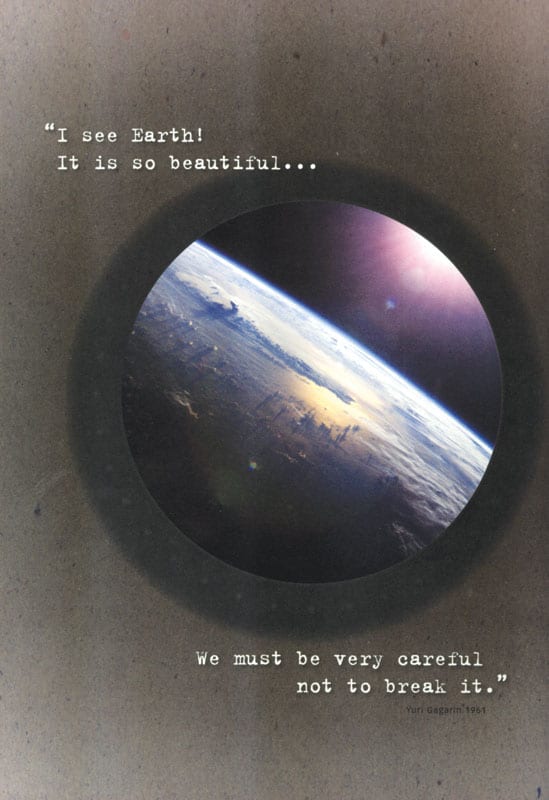

The too-short life of Yuri Gagarin was full of heroism and tragedy. Born in 1934 on a collective farm in western Russia, he became a child saboteur during the Second World War after the Nazis overran his village. After the war, he was selected for the Soviet Union’s first cosmonaut corps, and on 12 April 1961 he became the first man in space. Yuri’s Day: The Road to the Stars tells Gagarin’s story in an unusual format: as a “graphic novel”, or comic book. Together with the greyscale sketches of artist Andrew King, Piers Bizony’s text depicts events in Gagarin’s life in parallel with developments in the Soviet space programme. The contrasts with the better-publicized US effort are fascinating. For example, the Americans carried out experiments on weightlessness in cargo planes flown in parabolic curves – a trajectory that gave passengers a couple minutes of “zero g” at the top of each arc. The Soviets did the same in MiG training jets, but as the book explains, “their main solution [was] more drastic”: they dropped cosmonauts down the 28-storey Moscow State University lift-shaft in padded cages, cushioned with compressed air. Other episodes in the book are similarly infused with dark humour. After one early mission is aborted, a flight controller declares that although the craft has landed safely in Siberia, the canine cosmonaut inside is nevertheless doomed: “We already sent the ‘destruct’ signal. We can’t have foreign spies interrogating our dogs!” The ensuing farce ends happily for the dog, but other characters are less fortunate. Gagarin’s boss, Chief Designer Sergei Korolev, endured debilitating years as a political prisoner, and Gagarin himself was killed in a training flight less than seven years after his historic mission.

- 2010 Spaced Design Ltd £9.99pb 64pp; www.yuri-gagarin.com

Tales from the grassy knoll

In the 47 years that have passed since the assassination of US President John F Kennedy, numerous scholars have debated the “official” conclusion that Kennedy was killed by a single gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald. In this crowded field, G Paul Chambers stands out. For one thing, he is a physicist with a background in military research. For another, the cover of his book Head Shot: The Science Behind the JFK Assassination boasts that his is “the first book to identify the second murder weapon, prove the locations of the assassins [and] demonstrate multiple shooters with scientific certainty”. It is an intriguing premise, but for the most part, Chambers’ book does not live up to it. Though the author excels at pointing out inconsistencies in the official account – particularly in the penultimate chapter, which contains a physics analysis of the shot that killed Kennedy – his own argument is hardly free of them. For example, Chambers discounts medical evidence from Kennedy’s autopsy that calls his theory into question, and disparages ballistics experiments performed by the late Nobel-prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez, who used melons as a substitute for skulls, on the grounds that “melons are significantly different from human heads”. Elsewhere, however, he is quite happy to accept evidence based on shot-up bags of gelatine. Chambers also tries to smear Alvarez by noting that he failed to acknowledge government funding for his melon tests – implying (though he does not say so outright) that Alvarez had something to hide. While conspiracy theorists often claim that contradictory evidence is merely proof of a wider conspiracy, one expects better from an author such as Chambers, who repeatedly praises the scientific method.

- 2010 Prometheus Books £21.95/$25.00hb 240pp

A glowing tribute

When the graphic artist and biographer Lauren Redniss travelled to Paris to interview Marie and Pierre Curie’s granddaughter, Hélène Joliot-Langevin, she received a warning. “There are two traps when writing a biography of the Curies,” said Joliot-Langevin, herself a nuclear physicist. “One: to turn their story into a fairy tale. Two: to forget Pierre.” In Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout, Redniss has largely avoided both traps: Pierre plays a prominent role; and although the book is not a straightforward biography, it is not a fairy tale either. If anything, it is a work of art, packed with glowing collages and prints that owe a stylistic debt to both Picasso (off-kilter faces) and Matisse (bold-coloured cut-outs). Over the course of 200 richly illustrated pages, the reader learns about the Curies’ early years; their marriage and scientific collaboration; Pierre’s death and Marie’s subsequent affair; and the work of their daughter and son-in-law, Irene and Frederic Joliot-Curie. This biographical story is told well, with frequent quotations from the Curies’ own papers. However, some of the most interesting passages are actually detours, as the story floats freely from the lives of the Curies to the (half)-lives of the substances they discovered. The diverse voices represented in these interludes – a cancer patient, a survivor of the Hiroshima bombing, even an elderly couple receiving quack radon-gas treatments – help illuminate the Curies’ legacy, while also adding to the book’s somewhat dreamlike quality. Hard to describe, but easy to enjoy, this meditation on the life and legacy of Pierre and Marie Curie brings together art and science in a beautiful and thought-provoking way.

- 2011 HarperEntertainment/2010 It Books £19.99/$29.99hb 208pp