On uranium, the Big Bang, perfect planets and how to dunk your biscuits

History of an uneasy element

Among the Bemba people of central Africa, the word “shinkolobwe” is slang for “a man who is easy-going on the surface but who becomes angry when provoked”. It is also the name of the Congolese uranium mine that yielded raw material for the atomic bomb that flattened Hiroshima. As historical coincidences go, this one seems almost too good to be true. Still, one can hardly blame author Tom Zoellner for seizing upon it in Uranium: War, Energy and the Rock that Shaped the World, a very readable (if somewhat chaotic) history of how this normally easy-going element has provoked anger on five continents. After a scene-setting visit to the Shinkolobwe mine, Zoellner’s description of the Manhattan Project will contain few surprises for anyone who has read more comprehensive histories. One notable exception is his explanation of how the scientists got the uranium for the bomb. This tale of costly enrichment programmes, dubious middlemen and colonial skulduggery has important ramifications for the entire subsequent history of uranium. In chasing this history, Zoellner goes to an impressive amount of trouble to tell some of the less-heralded stories of the uranium age, talking to prospectors from Darwin, Australia, to Moab, Utah, and to one of the last survivors of an East German uranium gulag, where political prisoners dug the ore that built the Soviet nuclear arsenal. The price they paid was high – thousands died from radiation, non-existent safety precautions and maltreatment – but it was scarcely lower for miners in the West, where labour was unforced but just as hazardous. The universally cavalier attitudes to radiation during this period are sobering to contemplate. The book’s final chapters cover a grab-bag of topics from endemic fraud in Canadian uranium stocks to the question of whether terrorists could get enough uranium to build a bomb. It is not a question Zoellner cares to answer directly, but some may feel that the facts speak for themselves: on his visit to Shinkolobwe, he found the still-productive mine almost completely unguarded.

- 2010 Penguin £11.99/$16.00 pb 368pp

Questioning the cosmos

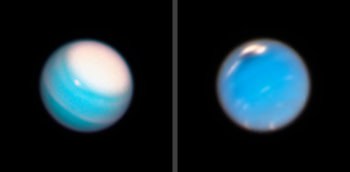

As a means of conveying scientific information, the “question and answer” format has a lot to recommend it: it is simple, straightforward and easy to follow. The downside is that books in this style tend to misjudge their audiences – after all, how do the authors know which questions readers want answered? For this reason, A Question and Answer Guide to Astronomy is a pleasant surprise. Written by engineer Pierre-Yves Bely and astrophysicists Carol Christian and Jean-René Roy (and recently translated from the original French into English), the book claims to give “simple but rigorous explanations” in “non-technical language”, and it does exactly what it says on the tin. Split into 10 sections, it answers hundreds of questions in fields ranging from planetary science (“What is the greenhouse effect?”) to astronomy and cosmology (“How do stars die?”). It also tackles trickier concepts such as “Can anything go faster than the speed of light?” and various big mysteries, including “What was there before the Big Bang?”. All the explanations are well expressed and usually aided by a full-colour illustration or photograph. Within explanations, the authors helpfully have embedded cross-references to other pages that may help to explain common concepts, allowing readers to skim through the questions focusing on the areas that interest them most. Towards the end, the book becomes more specialized, with 30 or so questions on telescopes followed by a propaganda-like section on how to get involved in astronomy. Despite this, the majority of the guide is informative, and by successfully tackling ideas that are often misunderstood, it makes for a worthwhile and enjoyable read.

- 2010 Cambridge University Press £18.99/$28.99 pb 294pp

First you have to look for them

The ever-expanding catalogue of worlds discovered outside our own solar system contains all sorts of planets: hot, cold, icy, rocky – you name it. But what about watery planets? Or those lovely, not-too-cold, not-too-hot “Goldilocks” ones with an active geology and perhaps a biggish moon nearby, just to keep things interesting? In How to Find a Habitable Planet, James Kasting begins by describing various factors that geophysicists, astrobiologists and others have deemed necessary (or at least desirable) for producing planets capable of supporting life. He then examines the evolutionary histories of the planets we know best – the Earth, Venus and Mars – in an attempt to determine why they developed the way they did. The book’s second half looks at ways of finding new planets using indirect methods (like measuring the tiny gravitational wobble imparted to a star when a planet passes nearby) before moving on to the challenges associated with detecting them directly. Being able to separate the faint reflected light of individual planets from the much brighter light of their parent stars “turns out to be a tall order”, writes Kasting. As a planetary scientist at Pennsylvania State University in the US, Kasting was involved in a design study for a space-based telescope that would have examined light reflected from the surfaces of extrasolar planets for clues about their composition. Unfortunately, the mission was cancelled while it was still in the design phase, and NASA has not yet revived it. How to Find a Habitable Planet offers an eloquent explanation of why such a mission would still be desirable.

- 2010 Princeton University Press £20.95/$29.95 hb 360pp

Weird science

Tired of biscuits that crumble into a soggy mess at the bottom of your teacup? Uncertain of the best technique for skimming stones across water? If you need answers to these pressing problems – plus advice on how to win at Trivial Pursuit and a rather invasive way to cure hiccups – then Dunk Your Biscuit Horizontally is the place to look. This light-hearted book of bite-sized strange science was compiled by the Dutch journalists Rik Kuiper and Tonie Mudde, and would make a great gift for anyone whose sense of humour encompasses both the scientific and the scatological. It is probably not one for younger children, though: the best cure for intractable hiccups turns out to be either good sex or “digital rectal massage”.

- 2010 Summersdale Books £7.99 pb 128pp