A collection of physics-themed books on topics ranging from aliens to zombies, reviewed by Margaret Harris

Murky business

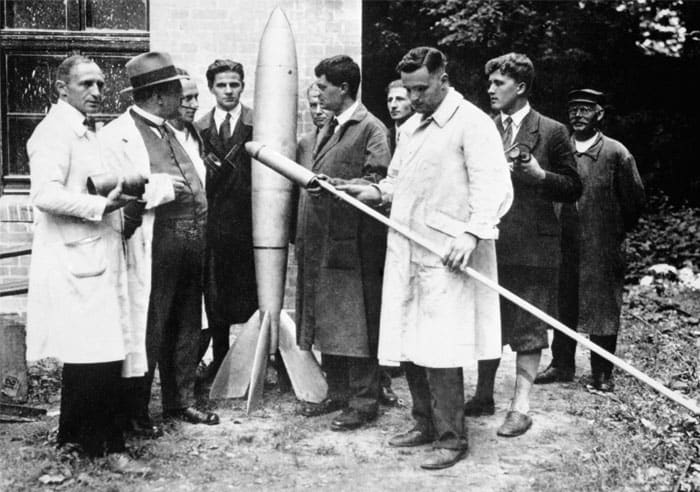

In the autumn of 1944, with the Second World War rumbling towards its nightmarish conclusion, a small group of Western scientists embarked on one of the Allied campaign’s more dubious missions. Their task was to locate and capture scientists who had served the crumbling Nazi regime, ferret out their secrets and put them to work in the war against Japan (and, later, in the Cold War against the Soviet Union). But as the US journalist Annie Jacobsen documents in her book Operation Paperclip, this theoretically justifiable goal soon collided with some ugly realities. At best, the scientists targeted by the operation were “apolitical” types who had turned a blind eye to atrocities as long as the research funds kept flowing. Many others, like the Nazi rocketeer turned father of the US space programme Wernher von Braun, had much dirtier hands than either they or their new American chums cared to admit. And a few were out-and-out war criminals. As Jacobsen shows, the distinction between who got hired and who got hanged was disturbingly fine. In one of the book’s most unsettling passages, she describes how representatives of an American group charged with arresting a suspected war criminal found their efforts stymied by an officer from a different US agency, which was trying to give that same war criminal a government contract. This would be farcical if it were not so horrible: the scientist in question, Otto Ambros, was a chemical weapons expert who had tested poison gas on concentration camp inmates, and had also managed the synthetic rubber factory at Auschwitz. Thoroughly researched and compellingly written, Operation Paperclip is a masterful critique of the ethics of science in wartime, and would make a good companion to Philip Ball’s book Serving the Reich, which focuses on the role of civilian physicists in Nazi Germany (February p42).

- 2014 Little, Brown $30.00hb/£12.99pb 592/576pp

The mathematical undead

Craig Williams teaches mathematics at a small liberal-arts college in western Massachusetts. Or at least he did, until the day a zombie shambled into his calculus class and started snacking on his students. Soon afterwards, the hero of Colin Adams’ delightfully silly novel/teaching aid Zombies and Calculus is holed up in an office with an assortment of sidekicks, including his biggest rival, his worst student, his onetime lover and the departmental secretary. Oh yes, and the rapidly zombifying local police chief, who got bitten in an earlier attack. At this point, Williams decides that what everyone really needs is a lesson on the mathematics of exponential growth (the better to model how the zombie epidemic is spreading), followed by a quick analysis of how much force is required to crack a zombie’s skull. This sets the pattern for the rest of the book, in which characters periodically take breaks from decapitating zombies in order to consider the finer points of exponential functions, differential equations and whether a fleeing university administrator can outrun the hordes of undead chasing him (spoiler alert: nope). It’s implausible, of course, but pleasingly surreal, and the mathematics is nicely done. If you are a current calculus student looking to spice up your revision, or a former one wanting to refresh your rusty u substitution skills, reading Zombies and Calculus is one of the most entertaining ways to do it.

- 2014 Princeton University Press $24.95/£16.95hb 240pp

We come in peace

Do-it-yourself motor enthusiasts have long relied on Haynes manuals to guide them through the ins and ours of automotive repair. A few years ago, fans of space exploration got a Haynes manual of their own, when the company honoured the 40th anniversary of the Moon landings by publishing an “owner’s manual” for the Apollo 11 mission (July 2009 p3). Now Haynes has taken the space theme to its logical conclusion (and perhaps beyond) by producing a manual for resisting alien invasion. Written by Sean Page and illustrated by Ian Moores, the Haynes Alien Invasion Owners’ Resistance Manual includes a step-by-step guide for making your own tin-foil hat and plenty of handy tips like “If they vaporize you with phasers, you know they’re hostile” and “Don’t get drawn into any discussion on time dilation, string theory or why they cancelled the TV series Firefly”. It’s all clearly tongue-in-cheek, and good for a few chuckles, but in some areas of the manual, the humour does have a bit of an edge to it. In particular, a page containing genuine, pro-UFO-sighting quotes from a British Royal Air Force chief, a Chinese general and two former US presidents (among others) brings to mind Poe’s Law of the Internet, which states (roughly) that there is no parody so absurd that someone won’t mistake it for the real thing.

- 2014 Haynes £16.99hb 128pp

No quick fix

According to Hinchliffe’s Rule, whenever the title of an academic paper is phrased as a question with a yes/no answer, the answer always turns out to be “no”. At first glance, Mike Hulme’s book Can Science Fix Climate Change? seems like a good example. In the book, Hulme, a climate scientist at King’s College London, strongly criticizes the idea that the Earth’s warming climate can (or should) be modified by injecting sunlight-blocking aerosols into the upper atmosphere. Such a technological “fix” would, he argues, be “undesirable” (because reducing temperature isn’t the same thing as controlling climate) “ungovernable” (because there is no mechanism for agreeing who would control the thermostat) and “unreliable” (because of the risks of unintended consequences). Of these three arguments, the second one is the most convincing. Because the benefits of such an intervention would be unevenly spread, Hulme notes that powerful states (and perhaps also non-state actors, such as corporations or eccentric billionaires) would have tremendous incentives to act in ways that favoured them. Injecting aerosols into the atmosphere is not, however, the only possible strategy for adjusting the Earth’s climate, and Hulme does not object to milder, more localized forms of “geoengineering” such as carbon capture and storage or painting roofs white to reflect sunlight. This suggests that the real answer to the question “Can science fix climate change?” is not a simple “no”, but rather something that depends on your definition of “science” or “fix”. A better, longer book might have weighed up the pros and cons of other scientific solutions, rather than focusing exclusively on the downsides of a single (rather barmy) one.

- 2014 Polity Press £9.99pb 144pp

Your inner scientist awaits

If you’ve already taught your dog quantum physics and relativity, what do you do for an encore? For Chad Orzel, whose first two popular-science books (How to Teach Quantum Physics to Your Dog and How to Teach Relativity to Your Dog) were based on imagined conversations with his German shepherd mix, the answer was simple: move on to humans. Specifically, humans who think they don’t like science very much. In his latest book, Eureka! Discovering Your Inner Scientist, Orzel sets out to convince people who regard science as “difficult” (or “nerdy”, or “esoteric”, or whatever) that they, too, are capable of thinking like scientists, and of applying the scientific method to whatever pursuits they find pleasant and meaningful. Pursuits like cooking, for example. As Orzel points out, successful chefs must master a repertoire of basic techniques, and then learn how to apply them in new situations. When they do this, he explains, they are following a path similar to that of the American physicist Luis Alvarez, who used techniques from particle physics to solve some notable problems in archaeology and geoscience. Readers who are already sold on the idea that science is useful and interesting are not, of course, Orzel’s primary audience here, but scientists will nevertheless find the stories in the book agreeably diverting – even if, ultimately, they are not completely convinced that what they do is comparable to baking a cake, playing basketball or bidding in a card game.

- 2015/2014 Basic Books £11.49/$17.99pb 368pp

Mixing maths and art

“Alice believes that Bob assumes that Alice believes that Bob’s assumption is incorrect.” If you didn’t follow the logic in that statement, it’s not your fault: it is, in fact, impossible for Alice to hold such a belief, because it is inherently self-contradictory. This conundrum is one of many fascinating little puzzlers found in John Barrow’s latest book, 100 Essential Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know About Maths and the Arts. Like its predecessor, in which Barrow, a mathematician at the University of Cambridge, expounded on 100 essential unknowns related to maths and sport, the book is well written and varied, with chapters on such diverse subjects as systems of finger counting, computability and betting. There’s just one problem: many of the chapters (including the Alice and Bob example above) have, at best, a very tangential connection to art. So why does “the arts” appear in the book’s title? According to Barrow, the answer is that mathematics and art are natural bedfellows, since they both involve the exploration and study of patterns. However, in reading the book, one gets the impression that Barrow’s real reason is simply that he finds them both interesting. Either way, it is probably best to ignore the words on the book’s cover and just enjoy the titbits inside.

- 2014 The Bodley Head £10.00hb 320pp