A call to arms for geeks, a panoply of scientific curiosities, an improbably fun book of odd experiments, a comedian’s view of rocket science, and puzzles from daily life – a bumper crop of books reviewed by Margaret Harris and Tushna Commissariat

Geeks of the Earth, unite

Are you bothered by misleading science stories in the media? Annoyed when political leaders confuse particle physicists and physicians (ahem, David Cameron)? Irate at ministers who select policies, then cast about for “evidence” to support them? Then according to Mark Henderson, it is time you stopped shouting at the television and started doing something. With The Geek Manifesto, Henderson – a former science editor at The Times newspaper – has produced a rare beast: a polemical book that offers solutions as well as rhetoric. One of the book’s main arguments is that scientists should take it upon themselves to become more engaged in the political process. As one of Henderson’s interviewees puts it in the book, “Scientists tend to feel that politics is something that happens to them, not something they can influence.” In fact, if scientists are prepared to make the first move, they may find politicians more receptive than they had assumed. Henderson does not, however, advocate asking politicians point-blank questions about science and using their replies as a “litmus test” for geek support. In a statement sure to provoke spluttering fury among a few Physics World readers, he suggests that a politician who can answer the question “What have you been wrong about?” may have a better understanding of science than one who can remember Newton’s laws of motion. A minister who reconsiders policies in light of new evidence, and abandons ones that fail, Henderson argues, is following the scientific method. For that, they deserve a bit of geek support, even if they lack formal scientific training. The book has a heavily British slant, and it certainly seems to have struck a chord among the nation’s geeks. Last summer, a campaign to send The Geek Manifesto to MPs raised enough money to buy copies for all 650 members of the House of Commons – though it helped that Henderson’s publisher, recognizing a golden publicity opportunity, stumped up some matching funds. Still, “geek power” remains a limited force, as demonstrated by the fate of Eureka magazine, which Henderson helped to launch as a monthly science supplement to The Times back in 2009. In the book, Henderson often touts Eureka as evidence of growing geek power, noting that the magazine is “chock-full of high-value advertisers who want to reach its readers”. Unfortunately, Eureka was canned in October – apparently due to, erm, poor advertising revenues. The geek movement, it appears, still has a long way to go.

- 2012 Bantam Press £18.99hb 336pp

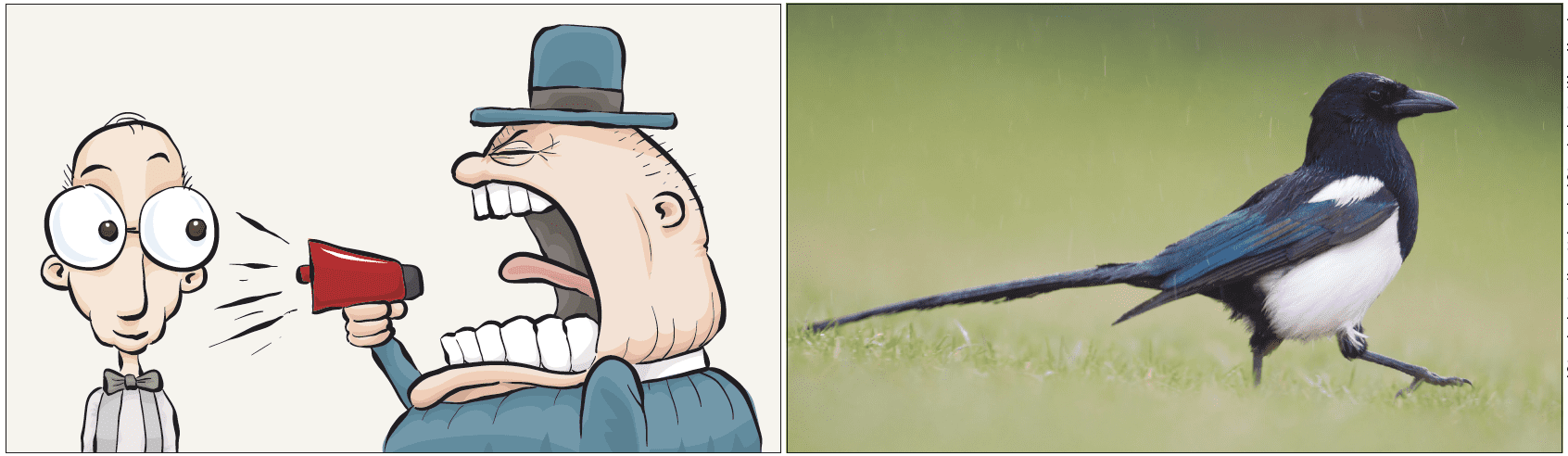

Into the magpie’s nest

As its name suggests, The Science Magpie is a panoply of scientific curiosities, plucked from the length and breadth of contemporary science as if by a curious and acquisitive bird. The “bird”, in this case, is a publisher-turned-trainee-teacher called Simon Flynn, who has gathered anecdotes, poems, jokes, facts and the odd diary entry or letter-to-the-editor, and put them together in no particular order to form a delightful little compendium of science oddities. The book includes some fairly well-known science trivia, including tales about Euler’s identity, Occam’s razor, Faraday’s Christmas lectures, Tom Lehrer’s song about “The Elements” and the Large Hadron Collider rap. But Flynn has also found some more obscure gems. A good example is Darwin’s diary entry, written when he was 29 years old, on the pros and cons of marriage. “Less money for books” was one particularly amusing “con”, while “charms of music and female chit-chat” was a “pro”. Another fascinating but gruesome story features the young Isaac Newton suffering for his science. As Flynn writes, during Newton’s studies of colour, “he talks of inserting a bodkin (like a cross between an arrow and a needle) between his eye and his socket as near to the back of the eye as possible. He would then press so as to change the retina’s curvature resulting in his seeing ‘white and darke and coloured circles’ as he continued to vary the pressure and movement”. Also in the book are questions from an 1858 Cambridge science exam for 15 year olds, mnemonics for remembering the geological timescale and the planets of our solar system, a little refresher on determining prime numbers and a handy list of the “10 greatest ever equations”. There is even a list containing the Scrabble scores of some common scientific words. On the whole, The Science Magpie is an easy and enjoyable read, and it will surely give you a host of new jokes and tales for the pub.

- 2012 Icon Books £12.99hb 278pp

Improbable fun

Most readers will have heard of the Ig Nobel Prizes, which are given annually to honour research that, in the words of Ig impresario Marc Abrahams, “first makes people laugh, and then makes them think”. This year’s physics Ig Nobel, for example, honoured an Anglo-American trio of researchers who calculated the balance of forces in human ponytails (March p3). Ceremonies for Ig Nobel winners have been held every year since 1991, and Abrahams has been publishing other examples of semi-silly science in his magazine, the Annals of Improbable Research, since 1995. But oddly enough, he has never grouped these tales together in book form – until now. This is Improbable: Cheese String Theory, Magnetic Chickens, and other WTF Research rehashes a number of past Ig Nobel citations, but delightfully, it also shows that such prize-winning research is the tip of an enormous iceberg. The economics of piracy, the lavatory habits of Antarctic researchers and the anti-skid benefits of wearing socks over shoes – all are described in glorious detail, with copious references to the original papers. As one might expect, many of these papers were published in obscure journals, but there are some surprising exceptions: the aforementioned ponytail research appeared in Physical Review Letters, while the case of a biologist who accidentally incubated more than 70 insects in his left sinus was published in Science. Maybe that one should have been billed as research that “first makes you laugh, and then makes you wince”.

- 2012 Oneworld £10.99/$15.95pb 320pp

Stand-up science

Actor and comedian Ben Miller is best known for being half of the comic duo “Armstrong and Miller” and for his other roles in film and television. What many do not realize, though, is that Miller was working on a physics PhD at Cambridge when, in his words, he “accidentally became a comedian”. In his new book It’s Not Rocket Science, Miller makes a partial return to his roots by focusing on the exciting bits of science, while avoiding complex maths and calculations. “If you want to build a Large Hadron Collider, you’d better hunker down and get a physics postdoc,” he writes. “If you want to gawp at one and imagine how cool it would be if one blew up…Well, you’ve come to the right place.” In the book, Miller covers a wide, if rather random-seeming, range of contemporary science ideas and subjects. After visiting CERN and whizzing through the Standard Model, he trips along the Milky Way while telling the reader that we are “slowly falling into an enormous black hole” that resides at the centre of our galaxy. He then dips into Darwin and evolution, and follows that thread to the intriguing science of genetics and DNA. A surprising chapter looks into cookery and the chemistry behind it – including the history of food and taste – and also contains a deeper examination of enzymes and molecular interactions that give distinct flavours. The book touches as well on the changing environment of Earth, weather prediction and the complex beast that is climate change, before ending with a look at the dynamics of heavenly bodies, space travel and – of course – aliens. If you are looking for a complete, in-depth view of contemporary science, this is not the book for you, since It’s Not Rocket Science was written mainly to entertain, not to inform. As Miller puts it, “This is not a science lesson. It’s a science orgy.” Still, you might learn something new along the way, without even trying.

- 2012 Sphere £12.99pb 280pp

The puzzles of daily life

We all know that everyday physical intuition is essentially useless for predicting the workings of the quantum-mechanical world. But as it turns out, intuition is not necessarily reliable even when it is applied to objects on a more familiar, macroscopic scale. Between 2003 and 2011 physicist Jo Hermans explored the complex and often counterintuitive nature of ordinary things via a series of columns in Europhysics News, the magazine of the European Physical Society. Now, these “Physics in Daily Life” columns have been published together in a book of the same name, complete with charming cartoon illustrations by Wiebke Drenckhan. Many of the collected columns begin with an incorrect “layman’s view” of a question. A good example is number 22, in which Hermans asks how many lights could be switched on with the energy required for a nice relaxing hot bath. The answer turns out to be around 1000 – far more than a physics-ignorant guesser might assume, although it doesn’t help that Hermans never specifies how long those lights could stay on. In other chapters, though, the much-abused “layman” turns out to be right. For instance, dark-coloured doors really do get hotter in sunlight than light-painted ones (number 15), even though a more sophisticated (but ultimately incorrect) reasoner might suggest that colour ought not to matter because “a surface that absorbs well must also emit well”. Hermans does a fair job of untangling all these conflicting assumptions and fragments of intuition, and the resulting clear, concise explanations are well worth reading.

- 2012 EDP Sciences €18pb 112pp