Margaret Harris and Matin Durrani review fiction books with a physics theme

Colliders, quants and mayhem

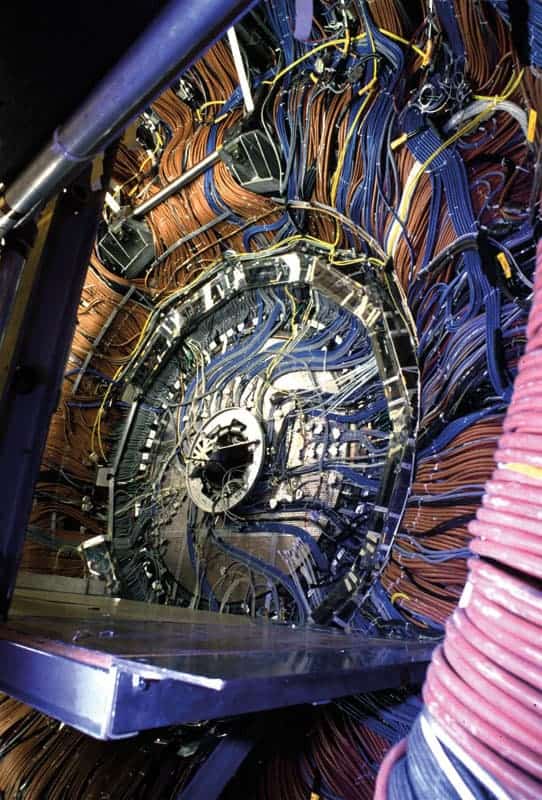

Robert Harris is perhaps best known for his trio of historical novels about ancient Rome that began with his 2003 bestseller Pompeii. Now, the former TV journalist has turned his hand to something very different with The Fear Index – a thriller about an ex-CERN particle physicist called Alexander Hoffmann who sets up an enormously profitable hedge-fund firm that trades on the global financial markets. The Geneva-based business employs a string of PhD quants, and the secret of its success is a powerful computer that exploits algorithms that Hoffmann developed while working on CERN’s Large Electron–Positron collider. The company is about to secure $2bn in extra cash from a range of rich investors when trouble strikes. In a series of bizarre and grisly plot twists, Hoffmann is violently attacked in his home, dumps his wife, murders someone in a downtown brothel and watches a fellow company director fall to his death down an open lift shaft. It would be churlish to spoil the denouement, but it will come as no surprise to say that it is pretty preposterous. As a character, Hoffmann does physicists few favours, coming across as odd, unfeasibly intelligent, unsociable and generally rather weird. However, there are enough references to real physics to make the story almost believable, including a quant who was “recruited from the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory”, various discussions of a financial function called “a delta hedge” and a building security code of 1729, which – the author reminds us – is the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways. Real CERN physicists will also enjoy the references to genuine Geneva locations. Interestingly, Harris thanks various members of the CERN press team, including media boss James Gillies, in the book’s acknowledgements. Overall, this is an entertaining if ultimately ridiculous story, not least for the supposedly geeky Hoffmann morphing into an action hero in the final few pages. File under “holiday reading”.

- 2011 Arrow/Hutchinson £18.99/ $25.95hb £7.99/$13.83pb 336pp

Dark labyrinths

Those who like their holiday reading a bit more cerebral may prefer an intriguing new trilogy by Stuart Clark, an astronomy journalist who has recently turned to writing fiction. The first book in the series, The Sky’s Dark Labyrinth, is set in the early 1600s, when Kepler and Galileo were breathing new life into Copernicus’s notion of a Sun-centred cosmos. With the second book, The Sensorium of God, the scene shifts to Restoration England, where Newton, Hooke and Halley are on the cusp of a scientific revolution. (The third book, The Day Without Yesterday, has not been published yet, but it will focus on Einstein.) Clearly, there is plenty of good material here, and Clark uses it remarkably well. Although many events depicted in the books will be familiar to Physics World readers, Clark has nevertheless managed to weave the likes of Kepler’s conflict with the Danish observer Tycho Brahe, Galileo’s struggles with the Inquisition and Newton’s feuds with, well, pretty much everyone into a vivid and even suspenseful narrative, full of secret plots as well as astronomical discoveries. At times, one can practically smell the aroma of London’s fashionable coffeehouses in Sensorium, or feel the tension in Labyrinth as mercenaries stalk the streets outside Kepler’s home in Prague. One thing that comes across particularly well in both books is the violence and uncertainty of the world in which these great astronomers lived. Over the course of the narrative, nearly all of them lose family members to disease, and many – not just the Catholic Galileo, but also heterodox Protestants like Kepler and Newton – also fall foul of their countries’ religious establishments. At times, Clark over-eggs the science versus religion conflict slightly; in particular, two non-historical characters (a malevolent cardinal in Labyrinth and a fanatical Anglican spy in Sensorium) seem to have been invented solely to amp up the “religious leaders behaving badly” theme. But then again, this is fiction, and a little exaggeration is no bad thing.

- 2011/2012 Polygon £8.99pb/£12.99hb 360pp/280pp

In the beginning

As opening lines go, the one in Alan Lightman’s novel Mr g takes some beating: “As I remember, I had just woken up from a nap when I decided to create the universe.” Simultaneously arresting and offhand, it perfectly encapsulates much of what follows in this curious little fable about a childlike god-figure (presumably the “Mr g” of the title) and the unexpected consequences of his decisions. Lightman is a theoretical physicist as well as a writer, and the early sections of this, his fifth novel, read like a fictional version of The First Three Minutes, Steven Weinberg’s classic account of the early universe Once Mr g has created time, he moves on to space, followed by dimensions, quantum physics and, eventually, matter. Not everything goes quite as planned. After Mr g formulates three “organizing principles” for his universe (which physicists will recognize as entropy, relative motion and the principle of cause and effect), he decides to arrange the comparative strengths of the universe’s fundamental forces into a pleasing ratio. What, he asks, could be more harmonious? But the result is a disaster: “almost immediately, the universe began writhing and straining…Evidently, the fourth law was not compatible with the first three.” And physics is not the only source of Mr g’s troubles. He must also deal with his squabbling Aunt Penelope and Uncle Deva, two other supernatural beings with whom he shares the formless Void, and the sinister Belhor – an entity that, like human suffering, is the unwished-for but possibly inevitable offshoot of Mr g’s creative efforts. The latter sections of the novel focus more on philosophy than physics, as Mr g experiments with creating conscious life directly, spars with Belhor over the consequences of free will, and keeps a close but largely non-interventionist watch over his creation. It is never clear what deep conclusions, if any, Lightman expects readers to draw from these antics, but to his credit the book retains much of its initial lightness until the very end – which, quite properly, comes not with a bang, but a whimper.

- 2012 Corsair/Pantheon $24.95/£9.99hb 256pp/224pp