Wombats are the only animals known to produce cubic droppings, and now a team of scientists claims to have worked out why. The team, based in the US and Australia, reckons that the unique elastic properties of tissues in the very last section of a wombat’s intestine cause the organ to become roughly square in cross section when expanded. As well as solving a long-standing biological mystery, the study could lead to new manufacturing techniques for cubic structures.

Wombats are Australian marsupials that live mainly in the south-east of the country and Tasmania. All three species of wombat are known to produce fairly uniform, cube-shaped droppings – but how they do it was not immediately obvious to biologists.

Moulding muscles or square anuses?

Past theories have suggested that wombats might have square anuses, that their pelvis compresses faecal matter as it passes through, and that blocks of intestinal muscles could mould faeces into cubes. According to the authors of the latest research, however, these hypotheses are all speculative and have not been investigated.

For their study, Patricia Yang at the Georgia Institute of Technology and her colleagues examined the intestines of two bare-nosed or common wombats (Vombatus ursinus) that had been euthanized after being hit by cars in Tasmania.

“The first thing that drove me to this is that I have never seen anything this weird in biology. That was a mystery,” said Yang. “I didn’t even believe it was true at the beginning. I Googled it and saw a lot about cube-shaped wombat poop, but I was sceptical.”

Luckily for the researchers, the dead wombats’ intestines were full of faecal matter. In the last 150 cm, or 25%, of the intestine the dimensions of the faeces were quite consistent, and much more solid than higher up in the bowel, they found. But when the team looked closely at the faeces in the final 50 cm, or 8%, of the intestine they discovered that it had sharp corners. This lead them to conclude that the cubic shape is formed in this final section of intestine, so they ran further tests on its properties.

Peak strain

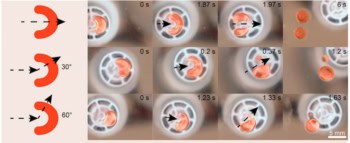

When they inflated a piece of this last section of intestine with a small balloon they discovered that its strain – or elasticity – varied around the intestines circumference. Three areas had an average peak strain of 75%, while two had an average peak strain of just 25%. For comparison, they checked an intestine from a pig and found that the average peak strain was fairly consistent around its circumference, at 53%.

The researchers say that this variation in strain helps mould the faeces into cubes, with the areas of high strain producing the corners, and the areas of low strain corresponding to the sides.

To produce a cube, however, four areas of high strain and four of low strain are needed, and they only found three and two, respectively. According to the researchers, the mostly likely explanation for this discrepancy is that the balloon did not stretch the tissue enough. The balloon was able to inflate the intestine to an 8 cm circumference, while some of the faeces they found would stretch the tissue to 9.6 cm. With further stretching you could reveal additional peak strains, they explain.

Soft tissue

Yang says that that the novel cube production method that wombats use could be applied to the manufacturing of cubic objects. “We currently have only two methods to manufacture cubes: We mould it, or we cut it. Now we have this third method,” she explains. “It would be a cool method to apply to the manufacturing process – how to make a cube with soft tissue.”

But, of course, the big question is why do wombats produce cube-shaped poo? There is some debate, but Scott Carver, an ecologist at the University of Tasmania, who was involved in the research, told Physics World, “The general belief is that it assists with stacking and not rolling away when they deposit it on or next to prominent landmarks within their home ranges – logs, rocks, small mounds – as a form of chemical communication.”

Yang presented her findings at the American Physical Society’s Division of Fluid Dynamics 71st Annual Meeting, in Atlanta earlier this month.