When faced with potential prey, how do predators know to avoid those that taste disgusting and potentially contain toxic chemicals? According to a study published earlier this week, for some birds at least, watching TV can help. The researchers, from Finland and the UK, showed that by watching videos of other birds eating, blue tits and great tits learn to recognise bad-tasting prey by their markings, without having to taste them first.

Many insects have conspicuous markings and bitter-tasting chemical defences to deter predators. But these warning markings are only effective once the birds learn to associate them with a disgusting taste – a skill that could potentially increase both the birds’ and their prey’s survival rate.

In the study, the researchers showed each bird a video of another bird’s disgust response – including vigorous beak wiping and head shaking – as it ate a bad-tasting “prey” item (almond flakes soaked in a bitter solution) from a paper packet marked with a square. Afterwards, TV-watching birds given a mixture of the bitter almond flakes and plain flakes in packets marked with a cross ate fewer of the disgusting packets.

“Blue tits and great tits forage together and have a similar diet, but they may differ in their hesitation to try novel food. By watching others, they can learn quickly and safely which prey are best to eat. This can reduce the time and energy they invest in trying different prey, and also help them avoid the ill effects of eating toxic prey,” explains first author Liisa Hämäläinen.

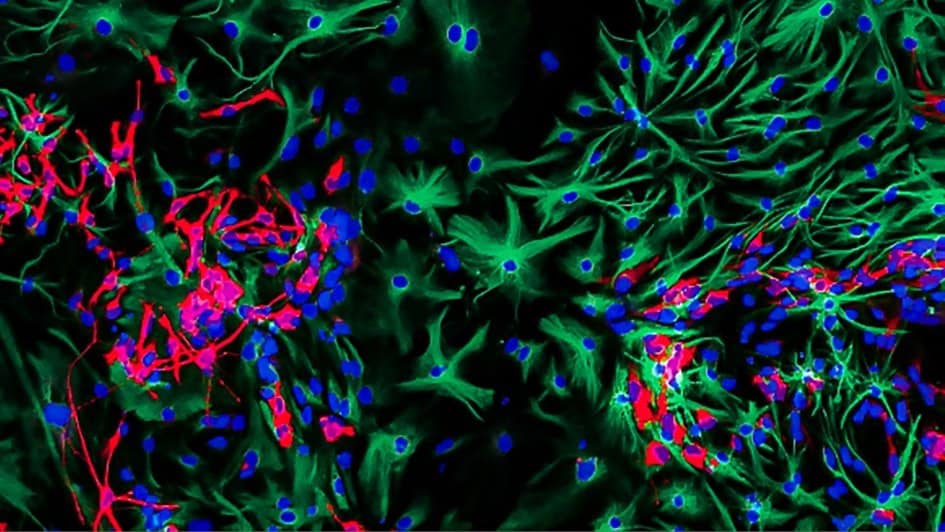

Is this a stunning new piece of modern art, or an information-rich scientific image? The Science and Medical imaging competition run by the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) highlights some of the most engaging and eye-catching images created by ICR and Royal Marsden researchers as part of their cancer research.

This year’s winner was “Differentiating brain cancer cells” by PhD student Sumana Shrestha. Taken using confocal microscopy, the colourful image shows neural stem cells from mice that are being used to study the aggressive brain cancer glioblastoma. Impressively, Shrestha also won the public vote, chosen via social media from eight of the competition’s most highly rated images, with a scanning electron microscopy image of dimpled “golf ball-like” microparticles that could be used to deliver drugs into the body.

Other images on the public shortlist included the first ever super-resolution microscopy image of focal adhesions – molecules that help cancer cells move and spread around the body – and a 3D image of an invading melanoma cell. The full selection of winning and shortlisted images can be seen on the ICR website.

Elsewhere, a US/Canadian research team is levitating human blood to detect opioid addiction. The researchers are using magnetic levitation to separate proteins from blood plasma. When separated, plasma proteins with different densities levitate at different heights and become identifiable. Optical images of the levitated proteins can help identify whether a patient has the possibility of getting a disease or becoming addicted to drugs such as opioids.

“We compared the differences between healthy proteins and diseased proteins to set benchmarks,” explains researcher Sepideh Pakpour. “With this information and the plasma levitation, we were able to accurately detect rare proteins that are only found in individuals with opioid addictions.” She notes that the team is particularly excited about the possibility of developing a new portable and accurate disease detection tool.

And finally, it’s time to pay tribute to Larry Tesler, the Apple employee who invented cut, copy and paste, who has died aged 74. Now we’re not saying Tesler had anything to do with the recent rise in plagiarism in academic publishing, but who’d have thought those two little keys CTRL-C and CTRL-V could cause such a stir? Now we’re not saying Tesler had anything to do with the recent rise in plagiarism in academic publishing, but who’d have thought those two little keys CTRL-C and CTRL-V could cause such a stir?