Adam Berlie is a muon instrument scientist at the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source in the UK, having done postdocs in China and Australia. He talks about his career so far, what it’s like to be a neurodivergent researcher, and his role as chair of the UKRI Disability Matters network

It was during my PhD studying metal-organic magnets at Durham University that I first started to realize that my approach to research made me different from my peers. I liked to work on lots of different projects at once and I was able to quickly switch between tasks in a way that other people sometimes struggled to understand. Looking back, I recognize that this was a sign of neurodivergence – in my case dyslexia and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) – though I wasn’t aware of this at the time.

Fortunately, I had two fantastic supervisors who encouraged my ability to see the big picture and I completed my PhD in 2013. I enjoyed pulling together lots of different strands of research rather than focusing on the details of a single project. However, having this kind of support hasn’t always been my experience. Though I now work as a researcher, as a teenager I wasn’t allowed to do a maths A-level and I was discouraged from doing physics because I wasn’t seen as being “quick and able” enough to cope with these subjects.

I have seen that many disabled scientists still feel that they have to camouflage and try to fit in, even if this negatively impacts their work. But neurodiversity has shaped my career; it has not only determined my choice of research projects but has also led me to my current role as the chair of the Disability Matters network at UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) – the umbrella body for the UK’s main research councils.

A different perspective

In fact, some people had originally discouraged me from doing a PhD in the first place. My first degree was in chemistry and my chosen path meant switching to physics at postgraduate level, which sometimes made me feel alienated from my colleagues.

However, I drew a lot on my knowledge of chemistry during my PhD, and I think that coming in with a different perspective benefited my work. In addition, being neurodivergent made the transition easier because I was used to switching between subjects and adapting to unfamiliar ways of thinking. My experience underscores why it’s so important to include people from diverse backgrounds in scientific research. This is true not only for subject area and neurodivergence but also for other characteristics like race and gender.

After my PhD, I took a postdoc position in China, studying organic-based magnetic and superconducting materials under high-pressure conditions. I worked at the Institute of Solid State Physics in Hefei, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. I then did a second postdoc in Australia, in a role that was split between the Australian National University and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO). I was involved in a huge range of research projects – I investigated solid-state organic and inorganic materials using techniques ranging from neutron spectroscopy to electron-spin resonance. But while I was there, I started to realize the limitations of postdoc work – producing results and pursuing the interests of someone else – when I was so driven by my own passions.

How networking can bolster diversity in physics

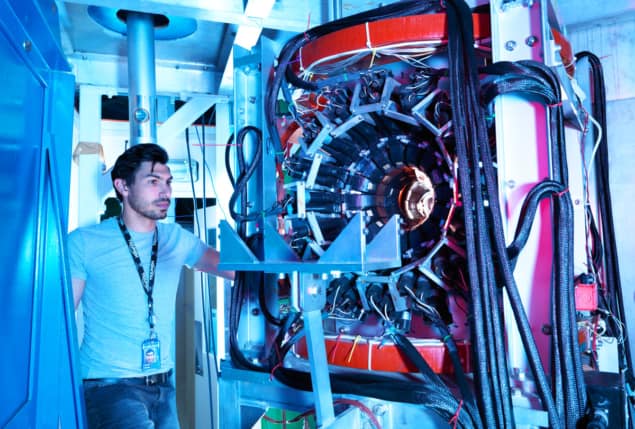

On returning to the UK in 2015, I joined the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source, and I’ve been here for eight years. Now I am building my own research programme, with the freedom to create a diverse and exciting portfolio, stretching from molecular and physical chemistry to quantum materials .

Tackling barriers for disabled scientists

However, there is still a lot to be done for neurodivergent researchers in the UK. For example, people with ADHD may struggle to manage organizational tasks, and I’m still pushing back against the idea that just because some things – such as writing and replying to e-mails – take longer for me than my neurotypical colleagues, I somehow haven’t earned my place as a researcher.

This frustration led me to become involved in disability advocacy in my workplace. The research sector is so important, and when you encounter barriers you have the opportunity to stand up and demand change. That’s where my work as chair of the UKRI Disability Matters network comes in. The network spans all of UKRI, encompassing research councils and facilities including the ISIS Neutron and Muon source. The network was set up in 2021 to make UKRI a more disability-inclusive workplace. I have found that many workplaces want to support disabled people, but they often don’t know what to do. One of our roles is to provide this expertise, as well as be a safe space for disabled colleagues to voice their concerns.

Diversity of thought benefits everyone, but when the focus is on the short-term costs of making changes, disabled people are often deterred from asking for what they need

As a researcher at the ISIS Neutron and Muon source, I also have the opportunity to put my beliefs into practice and foster a supportive environment for my colleagues. It’s important to take the initiative and ask people whether they have everything they need, and we should be willing to listen and make adjustments. Diversity of thought benefits everyone, but when the focus is on the short-term costs of making changes, disabled people are often deterred from asking for what they need.

Ask me anything: Lilly Liu – ‘We need team work: it’s impossible for one individual or team to solve a problem’

My experience shows that it is individual researchers themselves who understand what they need to succeed better than anyone else. That’s a message I want to share with others, and I am always happy to talk about my experience as a disabled researcher with individuals and organizations. Being the chair of the UKRI Disability Matters network is one of the proudest parts of my career.