A rare type of cancer affecting the lining of the lung, malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) has always been very difficult to treat. That may be about to change, though. Kazuhide Sato and his colleagues at Nagoya University have found a potential new treatment that combines light and a targeted antibody, according to their latest research published in Cells.

MPM, most often caused by exposure to asbestos, is often diagnosed late and has a very poor prognosis, with almost no options for treatment. To overcome this, Sato adapted a strategy recently developed for treating other cancers: near-infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT).

Illuminating the target

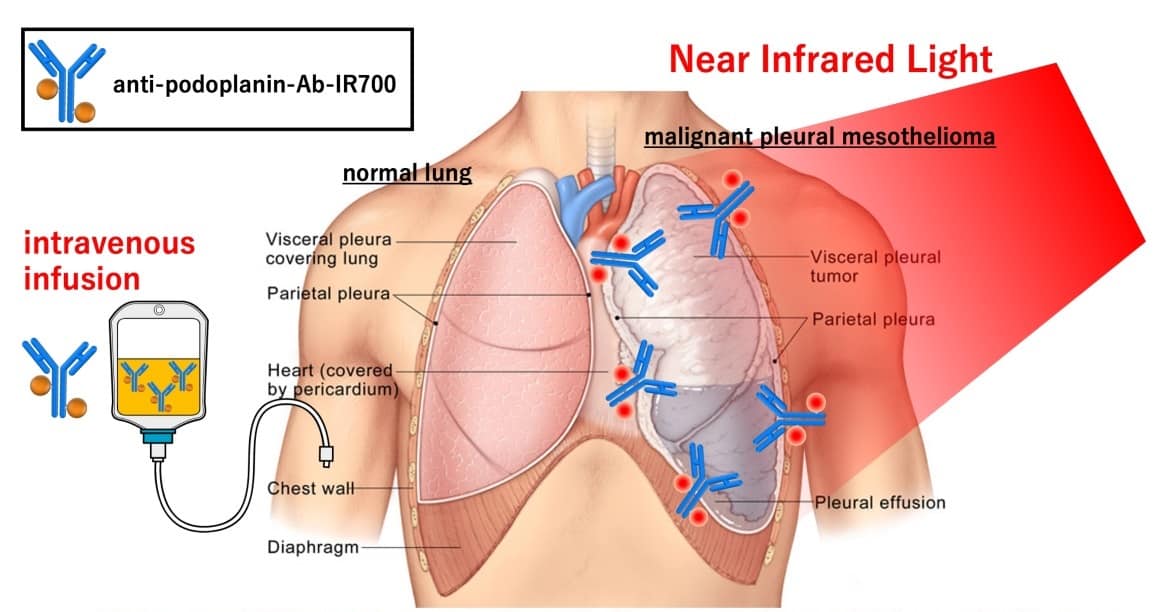

NIR-PIT combines two key methods together into one treatment. First, an antibody targets the tumour with precision. In this case, the antibody targets a protein called podoplanin, which is found in the membranes around the outside of cells. Whilst podoplanin is found on many cell types, certain cancers have a particularly large number of podoplanin proteins on their surface. MPM is one such cancer.

Next, the researchers attached to the antibody a drug molecule that is activated by exposure to NIR light. This light can be directed specifically at the site of the tumour.

Together, this antibody conjugate delivers and activates only the drug molecules in the targeted location – killing cancer cells with reduced damage to the rest of the body. This means fewer side-effects for the patient. The same method has already been given fast-track approval in the USA for treating a head-and-neck tumour. Thanks to this latest study, it may now also be adapted for MPM.

Seeing the light

The lung is a particularly good target for NIR-PIT, according to Sato. “The lungs and chest cavity contain a large amount of air and are thus very good at effectively transmitting near-infrared light,” he explains. That light is absorbed by the drug molecule – IR700 – attached to the antibody, which sticks to the outer membrane of the cancer cells. These cells then break apart and die.

In this study, the team showed that the antibody conjugate will bind to its target protein on the surface of cells. When exposed to NIR light, the team saw those cells swell, burst and die. This approach killed isolated cancer cells and, in mice with MPM tumours, caused a reduction in tumour volume compared with a control group of mice. Importantly, without the NIR light, the antibody conjugate caused no damage to the cells, showing how the treatment can be accurately targeted.

Whilst Sato and his team say that further work is required to ensure other, healthy cells with the same protein on their surface are not adversely affected, they envision that the method will be a promising anti-cancer strategy. It still needs extensive testing to prove its safety and performance in humans before use in the clinic. If successful, though, it may represent an important step forward towards treating an aggressive and often incurable cancer.