In June of this year, results from the first trial in humans of low-dose radiation therapy (LD-RT) for COVID-19 pneumonia were made publicly available by researchers at Emory University. The study, now formally published in Cancer, was followed soon after by a paper in the Red Journal, which also reported on the use of LD-RT to treat patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. This study, from Iran, examined five COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized and receiving supplementary oxygen for pneumonia. All were treated with a single fraction of 0.5 Gy whole-lung irradiation. Both trials had encouraging results, with 80% response rates. Since then, other similar trials of low-dose radiotherapy have started in the USA and elsewhere.

“This research has sparked a lively debate in the field,” said ASTRO president Laura Dawson, a professor of radiation oncology at the University of Toronto. “Results from published trials show the potential of LD-RT, but not a definite benefit, as these small studies have not been randomized. Also the potential for adverse long-term effects of this approach cannot be forgotten.”

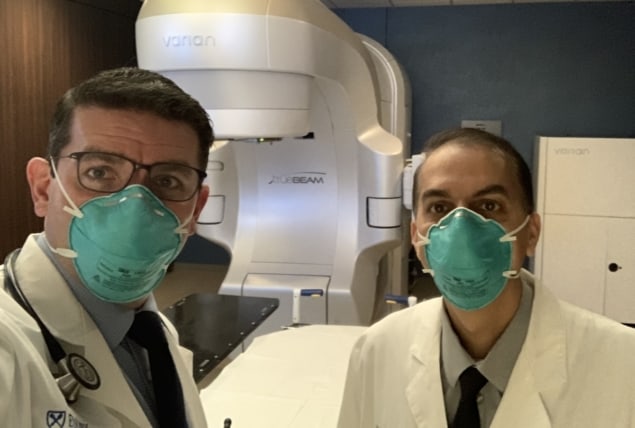

At the ASTRO 2020 Annual Meeting, Dawson introduced a panel discussion on “Low-dose radiation therapy and COVID-19-related pneumonia”. The first speaker, Mohammad Khan from Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, shared the results of the RESCUE 1-19 trial.

“RESCUE 1-19 was based on the hypothesis that LD-RT may help eliminate storming cytokines and unchecked oedema in hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” Khan explained. “This was the first LD-RT trial in the world.”

The trial, which examined COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized and required supplemental oxygen, comprised two phases. In phase one, the team treated five patients with 1.5 Gy whole-lung LD-RT, with a pre-planned day-seven interim safety analysis. By day seven, four of these patients exhibited significant clinical improvements and overall survival was 100%. The time to clinical recovery (no longer needing oxygen or being discharged from hospital) was 1.5 days, suggesting a possible benefit of LD-RT, without significant toxicity.

Following this finding, the team obtained approval to treat five more patients, as part of a phase two trial to assess the efficacy of LD-RT. These 10 patients’ outcomes were compared against 10 other patients that were age and comorbidity matched.

At day 28, the median time to clinical recovery was three days in the LD-RT group versus 12 days in the control group. Patients treated with LD-RT also left hospital earlier (median of 12 versus 20 days) and had lower intubation rates (10% versus 40%) compared with the controls. “LD-RT seems to suggest a statistically significant improvement in time to clinical recovery, at least in this cohort,” noted Khan.

The full study, reported in medRxiv and currently under peer review, also revealed differences in several inflammatory, cardiac and hepatic biomarkers between the two patient groups. The team also observed an improvement in serial X-rays in the LD-RT group within a few days.

“LD-RT for COVID-19 appears to be safe; there may be improvements in oxygen status, delirium, radiographic and other biomarkers when compared against matched cohorts treated with best COVID-directed therapies,” Khan concluded. “However this was only a small trial, confirmatory larger trials are needed.”

Randomized study

The next speaker, Arnab Chakravarti of The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, is leading two ongoing trials examining ultralow-dose thoracic radiation for COVID-19 patients.

The first, VENTED, is a phase II study of ultralow-dose whole-lung radiotherapy in critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. All patients in the study had been mechanically ventilated, and were treated with at least one dose of 80 cGy to whole thorax bilaterally, with the option for a second dose.

“Our hypothesis here is that low-dose thoracic radiation will decrease inflammation and improve outcomes for these intubated COVID-19 patients,” said Chakravarti. The trial’s primary objective is to evaluate the 30-day mortality rate after whole-lung LD-RT. The secondary objectives are primarily to assess the feasibility, safety and tolerability of this approach.

The second study is a multisite trial called PREVENT, which includes hospitalized COVID-19 patients who have severe respiratory compromise but are not yet intubated. The trial is currently running at several US institutions, with more sites scheduled to join shortly, including sites in other countries.

Step one of this trial compares patients randomized to receive either 35 cGy LD-RT, 100 cGy LD-RT or standard-of-care treatment. After interim dose selection, step two will compare patients treated with the preferred dose against the control group. The primary objectives are to determine which dose level is most efficacious and whether LD-RT at this dose is of clinical benefit. Secondary objectives include assessing the cost of care and patients’ quality-of-life.

“The ultimate question, to which we remain agnostic as a study team, is whether the potential benefits of LD-RT outweigh the risks,” emphasized Chakravarti. He noted that prior to launching these trials, the team had heard of institutions globally who were looking to treat patients using this LD-RT regimen off-protocol. “That drew a lot of concern from our study community and that was the rationale behind launching these two studies,” he explained.

Pros and cons

Also speaking in the panel session, Ramesh Rengan from University of Washington School of Medicine and Deborah Citrin of the National Cancer Institute examined the potential benefits and concerns of using LD-RT for COVID-19 patients.

“The question that we are wrestling with, with these studies, is whether or not LD-RT may have some value in short-term clinical management of the severe pulmonary inflammation rendered in patients due to COVID-19,” said Rengan.

This is a reasonable question to ask, he explained. In COVID-19, the viral infection triggers an inflammatory cascade – the cytokine storm – that overwhelms the lungs and can lead to respiratory failure. Currently, the only way to stop this is via corticosteroids, a systemic immunosuppressant. But as inflammatory cells are highly sensitive to radiation, and LD-RT has historically been used to effectively treat inflammatory diseases, could LD-RT could be used instead to suppress inflammation specifically within the lung?

Citrin explained how cells of different types have varying radiosensitivity, with most lung cells relatively resistant compared with immune cells. “Low-dose radiation can have not just killing effects on these immune cells but also change the way that some of the cells function,” she explained. For example, LD-RT can reduce the oxidative burst produced by macrophages that can damage lung tissue, and it can stop the growth of fibrocytes, the cells that make scar tissue and leads to lung fibrosis.

There are, however, important caveats to consider when irradiating the lungs. For starters, while LD-RT may confer an immediate benefit in terms of sterilizing inflammatory cells, if the radiation injures normal lung tissue, will this lead to inflammation weeks or months later?

“One of biggest concerns is the risk of long-term toxicity,” said Citrin. “In patients who are extremely ill, we have to balance the risk of injury or death from the virus, but we also need to consider the risk of long-term damage to heart or lung. We know that even at 1 Gy, there is a risk of cancer or cardiac damage.”

Such risks could be mitigated by treating patients at lower risk of second cancers or cardiac damage (those with shorter overall life expectancy), Citrin says. Long-term toxicity could also be reduced by finding the lowest dose that achieves a successful outcome, and determining whether to give the radiation in one low single dose or several even smaller doses.

COVID Research and Resources Group brings physicists together

There are also practical concerns when actively bringing COVID-19 patients into radiotherapy clinics: would this put particularly vulnerable cancer patients at increased infection risk? While early data are promising, there’s now a need for randomized trials, larger patient numbers and longer follow-up times to determine whether the immediate benefit is maintained.

“There are 15 ongoing multi-institutional prospective trials of LD-RT, some of which are randomized,” said Rengan. “These trials are important not only for providing information on the therapeutic benefit of LD-RT, but also to inform radiotherapy clinics about risk mitigation in terms of infection transmission and to help us understand how radiotherapy can best play a role as an immunosuppressive agent.”