Physicists in Germany have created a new type of X-ray laser that uses a resonator cavity to improve the output of a conventional X-ray free electron laser (XFEL). Their proof-of-concept design delivers X-ray pulses that are more monochromatic and coherent than those from existing XFELs.

In recent decades, XFELs have delivered pulses of monochromatic and coherent X-rays for a wide range of science including physics, chemistry, biology and materials science.

Despite their name, XFELs do not work like conventional lasers. In particular, there is no gain medium or resonator cavity. Instead, XFELs rely on the fact that when a free electron is accelerated, it will emit electromagnetic radiation. In an XFEL, pulses of high-energy electrons are sent through an undulator, which deflects the electrons back and forth. These wiggling electrons radiate X-rays at a specific energy. As the X-rays and electrons travel along the undulator, they interact in such a way that the emitted X-ray pulse has a high degree of coherence.

While these XFELs have proven very useful, they do not deliver radiation that is as monochromatic or as coherent as radiation from conventional lasers. One reason why conventional lasers perform better is that the radiation is reflected back and forth many times in a mirrored cavity that is tuned to resonate at a specific frequency – whereas XFEL radiation only makes one pass through an undulator.

Practical X-ray cavities, however, are difficult to create. This is because X-rays penetrate deep into materials, where they are usually absorbed – making reflection with conventional mirrors impossible.

Crucial overlap

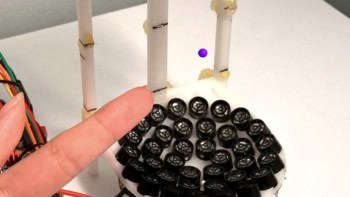

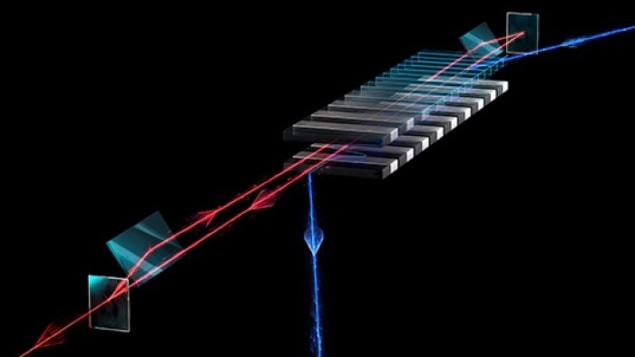

Now, researchers working at the European XFEL at DESY in Germany have created a proof-of-concept hybrid system that places an undulator within a mirrored resonator cavity. X-ray pulses that are created in the undulator are directed at a downstream mirror and reflected back to a mirror upstream of the undulator. The X-ray pulses are then reflected back downstream through the undulator. Crucially, a returning X-ray pulse overlaps with a subsequent electron pulse in the undulator, amplifying the X-ray pulse. As a result, the X-ray pulses circulating within the cavity quickly become more monochromatic and more coherent than pulses created by an undulator alone.

The team solved the mirror challenge by using diamond crystals that achieve the Bragg reflection of X-rays with a specific frequency. These are used at either end of the cavity in conjunction with Kirkpatrick–Baez mirrors, which help focus the reflected X-rays back into the cavity.

Some of the X-ray radiation circulating in the cavity is allowed to escape downstream, providing a beam of monochromatic and coherent X-ray pulses. They have called their system X-ray Free-Electron Laser Oscillator (XFELO). The cavity is about 66 m long.

Narrow frequency range

DESY accelerator scientist Patrick Rauer explains, “With every round trip, the noise in the X-ray pulse gets less and the concentrated light more defined”. Rauer pioneered the design of the cavity in his PhD work and is now the DESY lead on its implementation. “It gets more stable and you start to see this single, clear frequency – this spike.” Indeed, the frequency width of XFELO X-ray pulses is about 1% that of pulses that are created by the undulators alone

Ensuring the overlap of electron and X-pulses within the cavity was also a significant challenge. This required a high degree of stability within the accelerator that provides electron pulses to XFELO. “It took years to bring the accelerator to that state, which is now unique in the world of high-repetition-rate accelerators”, explains Rauer.

Team member Harald Sinn says, “The successful demonstration shows that the resonator principle is practical to implement”. Sinn is head of European XFEL’s instrumentation department and he adds, “In comparison with methods used up to now, it delivers X-ray pulses with a very narrow wavelength as well as a much higher stability and coherence.”

The team will now work towards improving the stability of XFELO so that in the future it can be used to do experiments by European XFEL’s research community.

XFELO is described in Nature.