The Chilling Stars: A New Theory of Climate Change

Henrik Svensmark and Nigel Calder

2007 Icon Books

256pp £9.99/$15.95 pb

For scientists, the archetypal romantic hero is the unappreciated pioneer working long hours while being scorned for his unorthodox, but ultimately correct, ideas. Galileo is the defining case, though picking just from the field of earth science, Svante Arrhenius, Milutin Milankovitch, Louis Agassiz, Guy Callendar and Alfred Wegener all endured their time in the wilderness before their ideas were finally vindicated. It is unsurprising then that many lone researchers who find their ideas criticized by the scientific establishment like to portray themselves in this light.

Unfortunately, while this “Galileo syndrome” is commonplace, most such ideas turn out to be wrong. The authors of The Chilling Stars would like you to believe that Danish physicist Henrik Svensmark’s controversial view of climate change is the genuine article. But since Svensmark himself is the lead author of this hagiography – irritatingly written in the third person with journalist Nigel Calder – one might be wise to take this declaration with a pinch of salt.

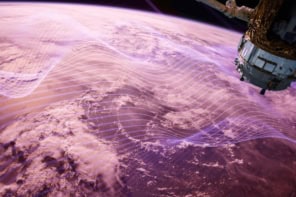

Svensmark’s idea, first mooted decades ago, is that the formation of clouds, and hence the climate, can be influenced by changes in the flux of galactic cosmic rays (GCRs). Claiming that GCRs have an impact on the climate by increasing the density of cloud-seeding aerosols is controversial in itself, as this mechanism has not been well established. But the authors go much further, stating that GCRs are actually the dominant driver of climate change on all timescales from days to billions of years, thus usurping humankind’s supposed contribution to 20th-century global warming through the release of greenhouse gases.

These are extraordinary claims, which will require extraordinary evidence to be accepted. It is therefore unfortunate that the book is more reminiscent of Immanuel Velikovsky’s 1950 bestseller Worlds in Collision – in which the author used ancient mythology to claim that the planet Venus was formed by a comet 3500 years ago – than it is of Galileo’s Dialogue. The link between GCRs and clouds is presented as fact, vague correlations are offered as proof, and everything in history – from the ice ages to the evolution of birds – is reinterpreted in the light of the “new” theory.

A clear example of the authors’ poor logic concerns trends in the Antarctic climate. They take two valid observations – that clouds have a net warming effect on Antarctica, but a cooling effect elsewhere; and that warming in the Antarctic has been less pronounced than across the rest of the globe – and declare that the two facts must be linked via a cosmic-ray effect on Antarctic clouds. Nowhere is there any evidence that Antarctic clouds are in fact correlated to GCRs; no other valid hypotheses (such as the known impact of the ozone hole on polar winds) are discussed, let alone disproved; and the “continental” temperature trend the authors use consists mainly of data from just one Antarctic island. But from this flimsy premise, they unquestioningly attribute all the anomalies of Antarctic climate (of which there are many in the climate record) to cosmic rays. This is scientific chutzpah of the highest order.

The dramatic centre of the book is the description of a recent experiment conducted by Svensmark and colleagues in which GCRs were shown to create small aerosol particles in “surprising” numbers in the lab. This is indeed interesting, and was rightly written up as a paper and published (Proc. R. Soc. A 463 385–396). However, it is far from the ultimate proof of their ideas that the authors claim. The researchers did not show that GCRs could actually produce much larger cloud condensation nuclei, even in the lab, nor how they would affect clouds in the real world even if they did.

In fact, in claiming that GCRs would only affect low-lying clouds and thus produce a cooling effect the authors display a breathtaking ignorance of the complexity of aerosol–cloud interactions. Yet these missing steps did not stop Svensmark from claiming that he had proved that GCRs have “an effect on everyday weather” in the press release accompanying the paper’s publication. For comparison, his theory is not even at the same historical point as the theory of greenhouse gases after John Tyndall’s experiments on the thermal properties of gases in the 1860s. Svensmark and colleagues do not seem to be aware of the huge amount of work that was necessary to get from there to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The last few chapters of the book are simply exercises in unconstrained speculation. Any event even vaguely correlated to a hypothetical change in GCRs must have been caused by it, regardless of the absence of evidence. A good example is the onset of the quaternary ice ages 2.6 million years ago. Preliminary work suggested that a large supernova occurred at this time, and the authors discuss at length how this would have led to cooling. Unfortunately for this hypothesis, the dating of the supernova was later revised; but rather than abandon the idea, the authors simply postulate that another as-yet-undetected event must have caused the change instead.

The common thread that is running throughout the book is that since GCRs must affect climate, it is just a question of finding the evidence. If one tack does not pan out, it is discarded and the next one picked up. This is a recipe for being led astray by spurious correlations and turns normal scientific practice on its head.

In reading the book, I was struck by some odd omissions. Nowhere is it mentioned that the first set of correlations between total cloud cover and GCRs published by Svensmark in 1997 disappeared in the light of new data. His second set of correlations, this time only with low cloud cover, are shown, but the fact that those correlations also broke down as the dataset was extended does not get a mention either. Nowhere is there a graph showing cosmic-ray fluctuations in recent decades. In fact, measurements show no significant trends and, since that undermines the authors’ claim that a reduction in GCRs is responsible for the current global warming, it is rather disingenuous to omit this information.

However, this just underlines the clear agenda evident throughout The Chilling Stars. It is not enough for the authors’ theory to succeed, they want the “opposing” greenhouse-gas theory to fail too. Computer modellers are apparently “silly” to be working on “fashionable” theories of anthropogenic global warming. But the reasons why are completely unclear. Are the calculations for the warming effects of carbon dioxide and methane incorrect? Do greenhouse gases have less effect on climate than GCRs? There is no mention of either here.

The authors would do well to consider that the criticism they have received is not due to the implications of their ideas, but to their track record of dubious and premature claims. The sad thing is that their underlying idea may have some merit, but a credible theory is unlikely to emerge from under the weight of this embarrassing bunk.