Ian Randall reviews The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World by Oliver Morton

Imagine a fleet of hundreds of stark, white, multi-hulled ships gliding majestically across the Pacific Ocean, untended by human hands. From each of these ships, three tall, ridged, spinning funnels reach skyward, sucking up seawater and spraying it high into the air. The spray seeds low-lying clouds with tiny salt particles, creating new condensation centres within the clouds that make them more reflective. By doing so, they increase the cooling effect that comes from reflecting incoming radiation back into space.

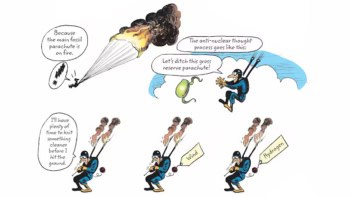

These so-called cloudships – the turn-of-the millennium brainchild of engineer Stephen Salter and physicist John Latham – are but one of a number of intriguing geoengineering concepts that aim to counter (or at least help mitigate) the effects of climate change. They, along with many other similarly outlandish ideas, are vividly brought to life in the pages of Oliver Morton’s new book, The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World. Morton is a journalist, and his book manages the rare knack of being both accessible and detailed. In it, he guides the reader through the history, politics and broad science of various geoengineering schemes, including the aforementioned cloudships, carbon capture from the air, the cultivation at sea of clouds of photosynthetic plankton and the formation of enormous stratospheric veils.

Most of the book is spent emphasizing the details and potential applications of this last concept, in which aerosols are injected into the stratosphere to help reduce the amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. The idea takes its inspiration from large-scale volcanic eruptions like that of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991, when this previously quiet peak dumped 20 million tonnes of sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere, temporarily forming a haze that cooled the globe by about 0.5 °C. Morton paints a vivid picture of veil-making, exploring not only the scientific principles behind such veils but also the kinds of aircraft and airships that would be needed to weave one across the skies. In the book’s conclusion, he also details a scenario for how the application and politics of veil-making might conceivably play out.

To suggest that The Planet Remade is just a discussion of various geoengineering concepts, however, would be to do it a considerable injustice. The book’s real strength lies in its superb richness, not only in its careful consideration of the impacts and politics of geoengineering but also in how it weaves its wide tapestry from so many varied, fascinating anecdotes. These include such gems as the seemingly outrageous proposal (by a British biologist, Julian Huxley) to improve the northern hemisphere by nuking the Arctic ice-cap out of existence; and physicist Freeman Dyson’s solution for lowering carbon-dioxide levels by growing sycamores on every uncultivated patch of land on which it was possible to plant them.

In an unexpected aside, the book also explores another striking human intervention in the Earth’s workings, but one that is less readily recognizable as a form of geoengineering: the large-scale manufacturing of fertilizer. Nitrogen availability is a limiting factor in the growth of many crops, and for it to be usable in biological synthesis, it needs to be “fixed” – that is, converted from its inert atmospheric form to ammonia. The development of the nitrogen-fixing Haber process in the early 20th century, Morton notes, “changed the conditions under which the human race lives” – accommodating a quadrupling of the human population and having an enormous impact on the nature of the Earth’s nitrogen cycle.

If the book’s greatest strength lies in its wonderful level of detail and history, its (infrequent) departures from this state of affairs reveals its only real weakness: Morton’s occasional tendency towards poetic philosophizing, which for this reader becomes, in places, a little too florid and relatively less compelling. My other small gripe with the work lies in its use of a new compound term, “earthsystem”. The expression is specifically introduced as a conceit to encourage readers to consider the Earth as a dynamic, interdependent network of parts – an essence, as Morton puts it, found “in all the Earth’s interplay of energy of matter”, in “the flows of energy which drive the cycles of carbon, water, nitrogen and life’s other essentials that roll ceaselessly round the planet and down through the eons”.

While the term certainly achieves this thought-provoking goal, it is not made clear why this “earthsystem” requires differentiating from the established geological term “Earth System”, the meaning of which appears to be identical. Overall, however, The Planet Remade was enriching and a pleasure to read – with much to appeal to both those unfamiliar and those more intimate with the concepts, history and politics of geoengineering.

- 2015 Granta Books £20.00/$29.95hb 448pp