Two new science-fiction TV series – Constellation and Dark Matter – reveal the problem of using the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics as a fictional device, say Robert P Crease and Jennifer Carter

“My understanding of identity has been shattered,” mulls the protagonist in Blake Crouch’s book Dark Matter (2016). “I am one facet of an infinitely faceted being called Jason Dessen who has made every possible choice and lived every life imaginable.”

Authors, poets, writers and film-makers have long exploited the notion of paths-not-taken as a narrative ploy. Early examples include Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” (1920), H G Wells’s novel Men Like Gods (1922) and Jorge Borges’s short story “The Garden of Forking Paths” (1941).

But the “many-worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics has turbocharged the genre, unleashing new possibilities for fiction about different choices, alternative lives and multiple worlds. Recent movies inspired by it include Another Earth (2011), Multiverse (2019), Loki (2021) and the award-winning Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022).

A fundamental principle of the many-worlds interpretation is that any contact between the different worlds is impossible. But a fundamental principle of popular culture is that it’s not, physics be damned. The beauty of using parallel worlds in fiction is that it can neatly exploit our human anxiety over the consequences of taking and having taken actions. In a sense, it reveals the God-like, world-shaping power of the human ability to choose and the depth of our innate desire to live our lives again.

As Brit Marling, co-author and star of Another Earth, told an interviewer: “Sometimes in science fiction you can get closer to the truth than if you had followed all the rules.”

Physics be damned

Quantum-inspired fictional worlds are back in the spotlight after featuring in two Apple TV+ dramas this year – Constellation and Dark Matter. Both use superposition as a device for allowing characters to take forking paths. The former was cancelled after one season, while the latter finished its season in June. The two shows illustrate what’s problematic about the genre.

In Constellation, characters feel and communicate with each other in different possible universes. The show highlights the uniqueness of the emotional ties we form and the joy or devastation we face when these links are severed or reconnected. It’s literally a haunting story where ghosts from other worlds alternately comfort and terrorize.

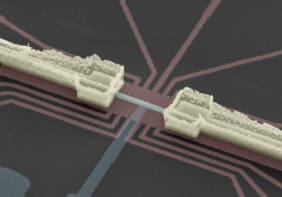

Dark Matter extracts somewhat more from superposition. Jason Dessen, a former physicist, has abandoned his brilliant career to spend more time with his wife, Daniela – who has also given up her career as an artist – and their child. In the alternate universe, where he did not give up his career, another Jason – let’s call him Alt-Jason – has used quantum superposition to create a “gateway to the multiverse” that “connects all possible worlds”.

Tired of fame and success, and his “intellectually stimulating but ultimately one-dimensional life”, Alt-Jason wants to take the “road not taken”. Using the gateway, he goes to Jason’s world, brutally beats Jason, sends him to Alt-Jason’s world, and assumes Jason’s role as husband and father. The book and series open with that switch; Jason has to figure out what’s happened and get back to “his” world and his family.

The characters in Dark Matter – the novel and the series – make predictable observations. Dessen, for instance remarks that “we’re a part of a much larger and stranger reality than we can possibly imagine”, and that “my identity isn’t binary…it’s multifaceted”. But the structure also makes possible imaginatively gripping scenes, such as Jason’s horrifying loneliness when he experiences seemingly insignificant things both familiar and unfamiliar, and a home that’s only “almost home”.

In one creepily intense scene, Daniela puzzles over the new quality of her love-making to the person she thinks is Jason but is actually Alt-Jason. We’re no longer like an “old married couple” but like “their first time every time”, she thinks. They smoulder with an intensity “that reminds her of the way new lovers stare into each other’s eyes when there’s still so much mystery and uncharted territory to discover”. It worries her, sort of.

Dark Matter – again, both the book and the TV series – give semi-explanations for the gateway. Thanks to quantum mechanics, scientists can put things in superposition to create worlds with an infinite number of possibilities. As the cliché goes: “Everything that can happen will happen.” People can enter superposition if they take a drug that prevents consciousness from destroying the superposition.

To enter superposition, they enter a box that uses the equivalent of what the show calls “noise-cancelling headphones” to block the intrusion of what would collapse the superposition. Once in superposition, they walk down a long corridor with an infinite number of doors leading to all possible outcomes. One’s frame of mind determines which world you enter.

The critical point

Previous Critical Point columns have provided a taxonomy of science-distorting art – “science bloopers” if you like (see columns from April 2007 and June 2007). Some distortions are well-meaning and create works that would be impossible otherwise, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Others, however, are due to inattention or stupidity. Even the title of the 1968 movie Krakatoa, East of Java is wrong (Krakatoa is west).

So are fictional works based on quantum-travel-between-worlds just examples of “harmlessly enabling distortion” (HED, done for a good purpose)? Or should we think of them as examples of “fake artistic distortion” (FAD, done for special effects without caring how science works)? It’s an interesting question especially for philosophers, who have long worried about art having to appeal to its audience’s “sense” of reality, and its tendency to reinforce that sense despite its distortions.

Ursula Le Guin: the pioneering author we should thank for popularizing Schrödinger’s cat

In a similar way, the appeal of TV series based on many-worlds interpretations depends on how agreeably and acceptably they manipulate popular preconceptions about quantum mechanics, such as about time travel, alternate worlds, the reality of superposition, and – most of all – the illusion that the fundamental structure of the world is up to us.

But wouldn’t it be more artistic to portray a universe where quantum systems are what they are – in some cases coherent systems that can decohere, but not via thought control (as in Dark Matter)? If we did that, then artists could speculate about what it’d be like to meet and even trade places with other selves without introducing fake scientific justifications. We could then try to understand if and why we would want or benefit from such identity-swapping, on both a physical and emotional level.

That might really shatter and reconfigure what it means to be human.

Robert P Crease (click link below for full bio) is a professor in the Department of Philosophy, Stony Brook University, US, where Jennifer Carter is a lecturer in philosophy