How to cool polar molecules

By Hamish Johnston

Talks at the APS are very hit and miss — especially for someone like me who wants a gentle introduction to a field rather than a full-on blitz of data and equations.

However, some talks are pure gold…it was definitely worth getting up early to hear Silke Ospelkaus’s 8 am lecture on how to create a gas of ultracold polar molecules.

Physicists have already perfected cooling atomic gases to very low temperatures using lasers — leading to a renaissance in the study of quantum systems.

Polar molecules are attractive because unlike ultracold atoms, they interact via long-range forces and thefore could be used to investigate a broader range of quantum phenomenon.

But molecules pose an additional challenge because they have rotational and vibrational energy, which must also be removed.

Although one could try to cool the atoms directly — or cool individual atoms and then combine them to make molecules — but both of these approaches have their problems.

According to Ospelkaus — who is at JILA in Boulder, Colorado — there is a better way. Her team began with “Feshbach molecules” which are made by taking ultracold potassium rubidium atoms and binding pairs together very weakly by applying an external magnetic field.

Although the molecules are ultracold, the separation between atoms is great, which means that they have a tiny dipole moment.

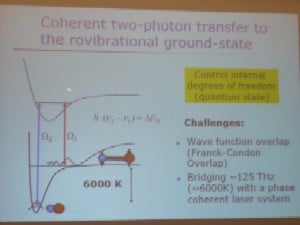

The next step is to gently coax the Feshbach molecules into the ground state of potassium-rubidium, which has a much higher dipole moment. This is tricky because there is very little overlap between the states. To get around this problem, Ospelkaus and crew shunted the Feshbach molecules into a third state that overlaps the two.

Easy right? Except that transition requires a 125 THz laser — and such things don’t exist!

Undaunted, Ospelkaus used the “beating” of two lasers to obtain light at the right frequency.

So after all that, did they manage to create a “quantum degenerate” gas?

Not quite, the team managed to get the molecules as cold as 400nK, whereas the onset of degeneracy is at about 100nK.

But now that they have a nearly degenerate gas of polar molecules Ospelkaus believes that it could be cooled further by applying electric fields.

…who said this sort of work was complicated?