The intensity of secondary cosmic rays reaching Earth is significantly correlated with mortality rates in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. That’s according to researchers in Brazil and the US.

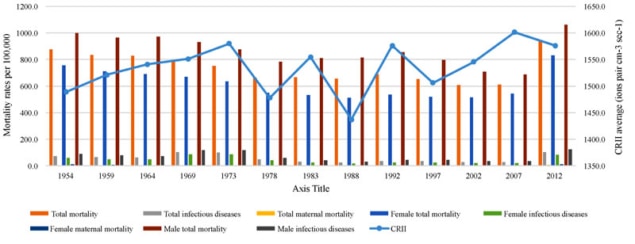

Looking at data over the past 60 years, the team found that the mortality rates for all diseases they identified were slightly – yet significantly – greater during periods of diminished solar activity, when cosmic rays are more intense, and slightly lower during heightened solar activity, when cosmic rays are less intense.

The link was stronger than the researchers expected. “I believed we could find significant results but we got surprised,” said Carolina Vieira of the University of São Paulo.

Cosmic rays consist of charged subatomic particles – mostly protons, but also helium nuclei and other particles – travelling near the speed of light, with energies upwards of 1 MeV. Originating mainly in the remnants of supernovae in our cosmic neighbourhood, they collide with gas molecules in our atmosphere, generating a cascade of secondary rays that can penetrate materials, including the human body.

Matter and electromagnetic fields emitted by the Sun partially protect us from cosmic rays. But the Sun’s activity rises and falls in an 11-year cycle, which means the intensity of secondary cosmic rays on Earth also follows 11-year cycles. Currently, the Sun is approaching a minimum in activity.

More locally, the intensity of secondary cosmic rays rises with latitude and altitude, so that in a city such as São Paulo, 23 ° south of the equator and 800 m above sea level, doses of secondary cosmic rays reach 0.2 nano-sieverts a year. For comparison, the International Commission for Radiological Protection allows uranium miners to receive 10,000 times more radiation a year.

“Although [the value for secondary cosmic rays in São Paolo] may seem to be relatively low, our results show that typical variation of cosmic-ray exposures to susceptible individuals, possibly radio-sensitive individuals, can lead to a highly significant increase of total mortality and specific mortality rates,” said Vieira.

Vieira was motivated to look into the possible health effects of secondary cosmic rays after she heard that in 2008 some children in her son’s school in São Paolo caught scarlet fever; a year later, the world suffered a swine-flu pandemic based on the same H1N1 influenza virus as the infamous 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. The events led her to wonder whether there could be an environmental agent changing the DNA of microorganisms to re-introduce certain diseases cyclically. “I decided to research what was going on,” she recalled.

Vieira and colleagues analyzed the correlation between the annual flux of secondary cosmic ray-induced ionization and various mortality rates in São Paolo using data from the period 1951–2012. Multivariate linear regression allowed them to show that the cosmic-ray ionization was correlated with total mortality, infectious disease mortality, maternal mortality, and perinatal mortality rates, with a p value of less than 0.001 – a p value less than 0.05 being the traditional threshold for significance.

“Annually, ~336 total deaths may be attributed to [secondary cosmic-ray] exposure in the city of São Paulo,” the researchers write.

They do not yet know the mechanism by which secondary cosmic rays could increase mortality rates, and are considering alternative explanations for the correlation. Since 2015, Vieira and colleagues have also been studying the possible interactions of cosmic rays, air pollutants and human health in US cities.

The study is published in Environmental Research Letters (ERL).