Fighting climate change with X-rays

By James Dacey

In the final day of my synchrotron sojourn I headed deep into the heart of the facility to meet some of the scientists hard at work.

In this dimly-lit environment, intense X-ray beamlines shoot off at tangents from the 844m electron beam as it screeches around the main storage ring – the giant polo you see from the air above Grenoble.

Researchers flock here from across the ESRF 12 member states (and beyond) to use these X-rays for probing all sorts of matter – to (hopefully) reveal new information about its fundamental properties.

Within this unusual office space, bicycle is the preferred way of getting around – as at many of the big-name particle colliders.

Highlight of the day for me was whizzing round on my red bike to beamline 15 – the most intense in the facility – to hear about the project taking place there. It had some very interesting environmental implications…

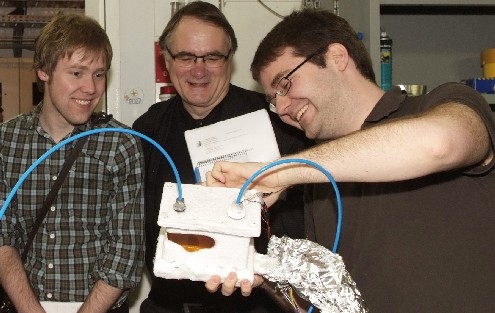

The researchers, from Germany and France, are using the X-rays to probe water-based crystal structures known as “hydrates”, which are capable of storing both hydrogen and carbon dioxide within their structures.

“If we can understand the chemistry and physics of how these hydrates form, this would be a great help for developing carbon sequestration technologies and feasible hydrogen-fuelled cars,” Felix Lehmkühler, one of the researchers, told me over lunch.

Since their latest publication , the researchers have been looking the effect of adding new compounds to their hydrates – the aim is to develop a structure that could store these important gases at everyday temperatures and pressures.

The good news for researchers like Lehmkühler is that the ESRF will be pouring 177 million Euros into upgrading all beamlines and research facilities over the next 6 years.

Meanwhile yesterday, over in California, the US Department of Energy were unveiling “the world’s brightest X-ray source” at the SLAC Accelerator laboratory.

“The science that will come from the LCLS will be as astounding and as unexpected as was the science that came from the lasers of a few decades ago,” said DOE Office of Science acting director, Patricia Dehmer.

With over 50 synchrotrons spread across five continents, and a road map in place to develop the first African facility, synchrotron research seems to be in a very healthy state right now!