Researchers in the US have invented a new type of electronic memory device. Stephen Forrest and colleagues at Princeton University and Hewlett-Packard made the device by combining a common plastic with silicon. The breakthrough could lead to an inexpensive way of storing data that is faster and simpler to use than a conventional compact disk writer (S Moller et al. 2003 Nature 426 166)

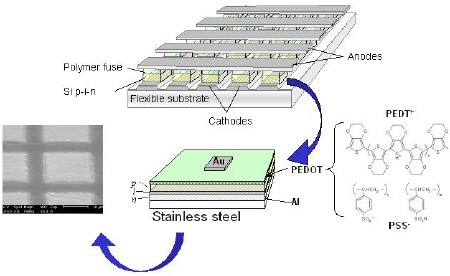

Researchers use polymers to make electronic devices such as diodes and transistors, but they have paid little attention to exploiting polymers as memory devices. Now, Forrest and colleagues have made a ‘write-once read-many-times’ (WORM) device by layering a conductive plastic called ‘PEDOT’ onto the surface of a thin-film silicon diode that has been deposited on a flexible metal foil. The data can only be written once because the write process causes permanent physical changes in the material. However, the data can be read and re-read indefinitely.

The Princeton-HP team discovered that PEDOT – which is used as a coating for photographic film and in video displays – conducts electricity at low voltages but becomes permanently non-conducting at higher voltages (of around 10 volts). It thus acts a fuse or circuit breaker.

In a memory device, data needs to be written as a string of ‘1s’ and ‘0’s. The new memory element would consist of a grid of circuits in which all the connections contained a PEDOT fuse. A large applied voltage would result in the fuse being blown and would close the circuit. This would be a ‘0’. At lower voltages, the fuse would remain intact, leaving the circuit open and would act as a ‘1’.

The researchers say that their technique could be used to make memory blocks as small as 1 square millimetre that were capable of storing 1 megabit of information. Although this is 100 times lower than the best magnetic memories, the device could find applications in ultra-low cost data archiving. Moreover, the memory would contain no moving parts – such as the laser and motor drives found in conventional magnetic and optical writers.

The team now hopes to turn their invention into a commercially viable product. “This could take as little as five years,” says Forrest.