Leopard geckos were used as a control in this study Source <a href="http://www.freedigitalphotos.net/

“>freedigitalphotos

By James Dacey

A few years ago, physicsworld.com reported the first experimental evidence to explain how a gecko can scurry without fear across even the smoothest of ceilings.

The answer lies in the lizards’ hairy feet. Each toe one is covered with tiny micrometer “satae”, which branch off into even smaller “spatulae” thinner than the wavelength of visible light. Spatulae stick to walls by van der Waals forces – the weak electrostatic attractions between adjacent atoms or molecules that arise from fluctuations in the positions of their electrons. If these forces act over a relatively large area, they can build up a significant attractive force.

Now, inspired by the gecko’s sticky trick, a couple of researchers in Canada and the US have set out to investigate where and when this stickiness is switched on and off by the lizards.

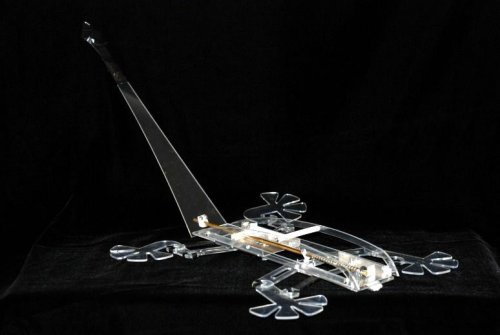

Anthony Russell of the University of Calgary and his colleague Timothy Highan of Clemson University, South Carolina, began by assembling a team of 11 geckos. Six of these were Moorish geckos, T. Mauritanica, which are known to use the van der Waals gripping mechanism. The remaining five were juvenile leopard geckos, E. Macularius, used as controls because they do not have adhesive pads.

Russell and Higham set up an experiment in which all 11 geckos were made to run across a set of different surfaces over a range of different inclines. On the flat surfaces, the researchers found that all six Moorish geckos refrained from using their adhesive system. However, when the geckos were running on a 10 degree incline, three of them began to use their pads for grip, and on a 30 degree incline, all six deployed their pads.

Interestingly, the friction of a running surface seems to make no difference to whether geckos deploy their gripping mechanism or not. None of the Moorish geckos used their sticky pads on the flat planes even when they were slipping on the Plexiglas substrate and losing speed because of this. This observation led the researchers to conclude that geckos control their sticky toes by via a perception of their body’s orientation.

I caught up with Russell and he explained the findings in a little more detail. “The loading of the setae under tension is accomplished by the muscular system, and that this, in turn, is activated by reflex pathways that depend upon feedback from environmental cues, such as body orientation.”

So, it seems that the insights of this new research are more related to the application of the physics by the animal, rather than the details of the physics itself.

One thing I found interesting when reading the paper — just published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B — is the difficulty the researchers must have faced when trying to control variables in an experiment like this. It’s not like certain experiments in classic physics in which one can take thousands of measurements of an inanimate object in a vacuum.

Russell conceded himself that he cannot draw any general laws from this because there are hundreds of species of gecko and we cannot expect them all to respond in the same way. “Even small and large individuals of the same species may not respond in the same way.”