By Margaret Harris

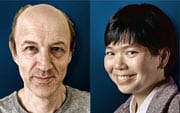

It’s been a good week for the astronomers David Jewitt and Jane Luu.

On Tuesday, the pair – whose discovery of the Kuiper belt of small, icy objects back in 1992 quickly reshaped our understanding of the outer solar system – learned that they had won this year’s Shaw Prize in Astronomy. This is a pretty big deal. The nine-year-old Shaw prizes are a relatively new kid on the scientific-awards block, but the astronomy prize already has a prestigious track record: previous winners include both last year’s dark-energy Nobel laureates (Saul Perlmutter, Adam Riess and Brian Schmidt) and the exoplanet pioneers Geoff Marcy and Michael Mayor. Oh yes, and each Shaw prize is also worth a cool $1m, which is a fair whack even in this age of inflation and economic uncertainty.

But Jewitt and Luu’s week wasn’t over yet. Earlier today, Norway’s Kavli Foundation announced that Jewitt and Luu had also won its big astro gong: the Kavli Prize in Astrophysics. They’ll share this honour – and its attendant $1m prize pot – with a third astronomer, Michael Brown, who followed up on Jewitt and Luu’s Kuiper-belt observations by discovering some of the region’s largest objects, including the Pluto-sized body known as Eris.

So what happens when you win two major science prizes in a week? I contacted Jewitt and Luu shortly after the prizes were announced, and although neither had much time to talk – “I am not being snooty, it’s just that all the deadlines are converging right now,” Luu explained in an e-mail – Jewitt said it was “very flattering” that two independent prize committees had come to the same decision about their work. Their long and ultimately successful search for objects beyond Neptune’s orbit had, he added, triggered an “explosion” of research into planet formation and the evolution of the outer solar system. For example, subsequent studies of the Kuiper belt have shown that it is the source of most of the comets that pass the Earth, since the proximity of Neptune’s gravitational well alters the trajectory of nearby objects and scatters them into the inner solar system.

As for what the pair plan to do with the prize money, Luu – who began her award-winning work as a PhD student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is now a technical member of staff at the institute’s Lincoln Laboratory – said that was a tough question, and winning a second prize made it even tougher. However, she added that “it is a good problem to have, so I am certainly not complaining”.

Jewitt, who was Luu’s PhD advisor and is now a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, took a slightly more direct view. “Like many people, I’m massively in debt,” he told physicsworld.com. “The prize[s] might help there, but I haven’t decided yet.”