When chunks of space debris make their fiery descent through the Earth’s atmosphere, they leave a trail of shock waves in their wake. Geophysicists have now found a way to exploit this phenomenon, using open-source seismic data from a network of earthquake sensors to monitor the waves produced by China’s Shenzhou-15 module as it fell to Earth in April 2024. The method is valuable, they say, because it makes it possible to follow debris – which can be hazardous to humans and animals – in near-real time as they travel towards the surface.

“We’re at the situation today where more and more spacecraft are re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere on a daily basis,” says team member Benjamin Fernando, a postdoctoral researcher at Johns Hopkins University in the US. “The problem is that we don’t necessarily know what happens to the fragments this space debris produces – whether they all break up in the atmosphere or if some of them reach the ground.”

Piggybacking on a network of earthquake sensors

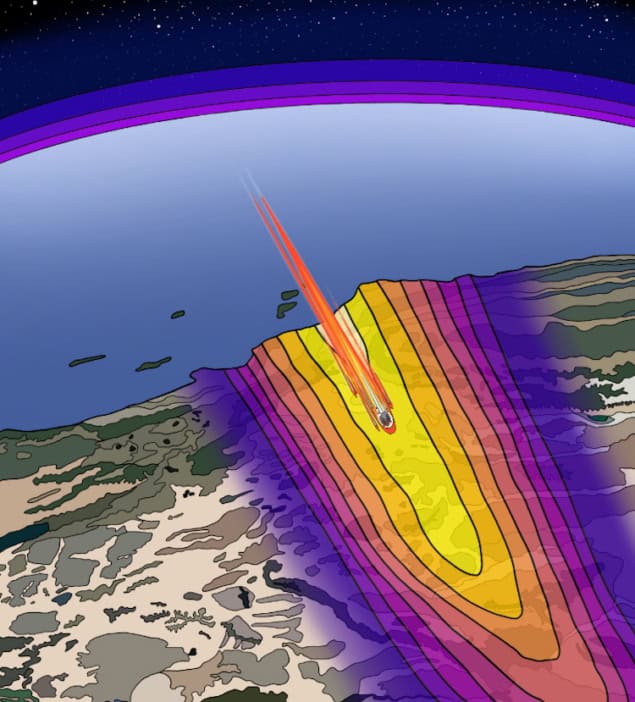

As the Shenzhou-15 module re-entered the atmosphere, it began to disintegrate, producing debris that travelled at supersonic speeds (between Mach 25‒30) over the US cities of Santa Barbara, California and Las Vegas, Nevada. The resulting sonic booms produced vibrations strong enough to be picked up by a network of 125 seismic stations spread over Nevada and Southern California.

Fernando and his colleague Constantinos Charalambous at Imperial College London in the UK used freely available data from these stations to measure the arrival times of the largest sonic boom signals. Based on these data, they produced a contour map of the path the debris took and the direction in which it propagated. They also determined the altitude of the module as it travelled by using ratios of the speed of sound to the apparent speed of the incident wavefront its supersonic flight generated as it passed over the seismic stations. Finally, they used a best-fit seismic inversion model to estimate where remnants of the module may have landed and the speed at which they travelled over the ground.

The analyses revealed that the module travelled roughly 20-30 kilometres south of the trajectory that US Space Command had predicted based on measurements of the module’s orbit alone. The seismic data also showed that the module gradually disintegrated into smaller pieces rather than undergoing a single explosive disassembly.

Advantages of accurate tracking

To obtain an estimate of the object’s trajectory within seconds or minutes, the researchers had to simplify their calculations by ignoring the effects of wind and temperature variations in the lower troposphere (the lowest layer of the Earth’s atmosphere). This simplification also did away with the need to simulate the path of wave signals through the atmosphere, which was essential for previous techniques that relied on radar data to follow objects decaying in low Earth orbit. These older techniques, Fernando adds, produced predictions of the objects’ landing sites that could, in the worst cases, be out by thousands of kilometres.

The availability of accurate, near-real time debris tracking could be particularly helpful in cases where the debris is potentially harmful. As an example, Fernando cites an incident in 1996, when debris from the Russian Mars 96 spacecraft fell out of orbit. “People thought it burned up and [that] its radioactive power source landed intact in the ocean,” he says. “They tried to track it at the time, but its location was never confirmed. More recently, a group of scientists found artificial plutonium in a glacier in Chile that they believe is evidence the power source burst open during the descent and contaminated the area.”

Though Fernando emphasizes that it’s rare for debris to contain radioactive material, he argues “we’d benefit from having additional tracking tools” when it does.

Towards an automated algorithm for trajectory reconstruction

Fernando had previously used seismometers to track natural meteoroids, comets and asteroids on both Earth and Mars. In the latter case, he used data from InSight, a NASA Mars mission equipped with a seismometer.

“The meteoroids hitting the Red Planet were a really good seismic source for us,” he explains. “We detected the sonic booms from them breaking up and, occasionally, would actually detect the impact of them hitting the ground. We realized that we could actually apply those same techniques to studying space debris on Earth.

“This is an excellent example of a technique that we really perfected the expertise for a planetary science kind of pure science application. And then we were able to apply it to a really relevant, challenging problem here on Earth,” he tells Physics World.

China’s Shenzhou-20 crewed spacecraft return delayed by space debris impact

The scientists say that in the longer term, they hope to develop an algorithm that automatically reconstructs the trajectory of an object. “At the moment, we’re having to find the sonic boons and analyse the data ‘by hand’,” Fernando says. “That’s obviously very slow, even though we’re getting better.”

A better solution, Fernando continues, would be to develop a machine learning tool that can find sonic booms in the data when a re-entry is expected, and then use those data to reconstruct the trajectory of an object. They are currently applying for funding to explore this option in a follow-up study.

Beyond that, there’s also the question of what to do with the data once they have it. “Who would we send the data to?” Fernando asks rhetorically. “Who needs to know about these events? If there’s a plane crash, hurricane, or similar, there are already good international frameworks in place for dealing with these events. It’s not clear to me, however, that such a framework for dealing with space debris has caught up with reality – either in terms of regulations or the response when such an event does happen.”

The current research is described in Science.