Quantum mechanics famously limits how much information about a system can be accessed at once in a single experiment. The more precisely a particle’s path can be determined, the less visible its interference pattern becomes. This trade-off, known as Bohr’s complementarity principle, has shaped our understanding of quantum physics for nearly a century. Now, researchers in China have brought one of the most famous thought experiments surrounding this principle to the quantum limit, using a single atom as a movable slit.

The thought experiment dates back to the 1927 Solvay Conference, where Albert Einstein proposed a modification of the double-slit experiment in which one of the slits could recoil. He argued that if a photon caused the slit to recoil as it passed through, then measuring that recoil might reveal which path the photon had taken without destroying the interference pattern. Conversely, Niels Bohr argued that any such recoil would entangle the photon with the slit, washing out the interference fringes.

For decades, this debate remained largely philosophical. The challenge was not about adding a detector or a label to track a photon’s path. Instead, the question was whether the “which-path” information could be stored in the motion of the slit itself. Until now, however, no physical slit was sensitive enough to register the momentum kick from a single photon.

A slit that kicks back

To detect the recoil from a single photon, the slit’s momentum uncertainty must be comparable to the photon’s momentum. For any ordinary macroscopic slit, its quantum fluctuations are significantly larger than the recoil, washing out the which-path information. To give a sense of scale, the authors note that even a 1 g object modelled as a 100 kHz oscillator (for example, a mirror on a spring) would have a ground-state momentum uncertainty of about 10-16 kg m s-1, roughly 11 orders of magnitude larger than the momentum of an optical photon (approximately 10-27 kg m s-1).

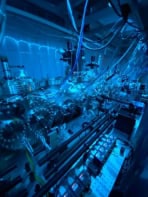

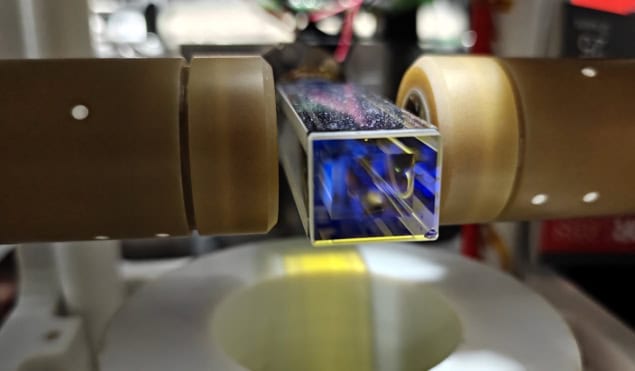

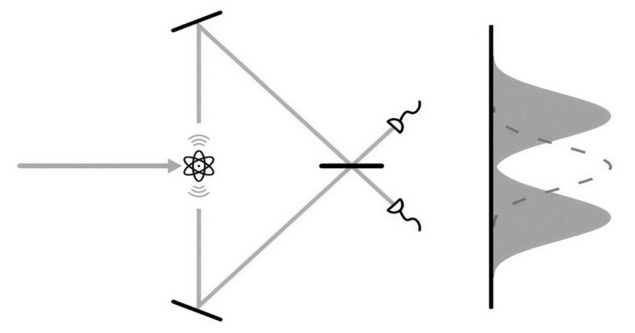

In their study, published in Physical Review Letters, Yu-Chen Zhang and colleagues from the University of Science and Technology of China overcame this obstacle by replacing the movable slit with a single rubidium atom held in an optical tweezer and cooled to its three-dimensional motional ground state. In this regime, the atom’s momentum uncertainty reaches the quantum limit, making the recoil from a single photon directly measurable.

Rather than using a conventional double-slit geometry, the researchers built an optical interferometer in which photons scattered off the trapped atom. By tuning the depth of this optical trap, the researchers were able to precisely control the atom’s intrinsic momentum uncertainty, effectively adjusting how “movable” the slit was.

Watching interference fade

As the researchers decreased the atom’s momentum uncertainty, they observed a loss of interference in the scattered photons. Increasing the atom’s momentum uncertainty caused the interference to reappear.

This behaviour directly revealed the trade-off between interference and which-path information at the heart of the Einstein–Bohr debate. The researchers note that the loss of interference arose not from classical noise, but from entanglement between the photon and the atom’s motion.

“The main challenge was matching the slit’s momentum uncertainty to that of a single photon,” says corresponding author Jian-Wei Pan. “For macroscopic objects, momentum fluctuations are far too large – they completely hide the recoil. Using a single atom cooled to its motional ground state allows us to reach the fundamental quantum limit.”

Maintaining interferometric phase stability was equally demanding. The team used active phase stabilization with a reference laser to keep the optical path length stable to within a few nanometres (roughly 3 nm) for over 10 h.

Famous double-slit experiment gets its cleanest test yet

Beyond settling a historical argument, the experiment offers a clean demonstration of how entanglement plays a key role in Bohr’s complementarity principle. As Pan explains, the results suggest that “entanglement in the momentum degree-of-freedom is the deeper reason behind the loss of interference when which-path information becomes available”.

This experiment opens the door to exploring quantum measurement in a new regime. By treating the slit itself as a quantum object, future studies could probe how entanglement emerges between light and matter. Additionally, the same set-up could be used to gradually increase the mass of the slit, providing a new way to study the transition from quantum to classical behaviour.