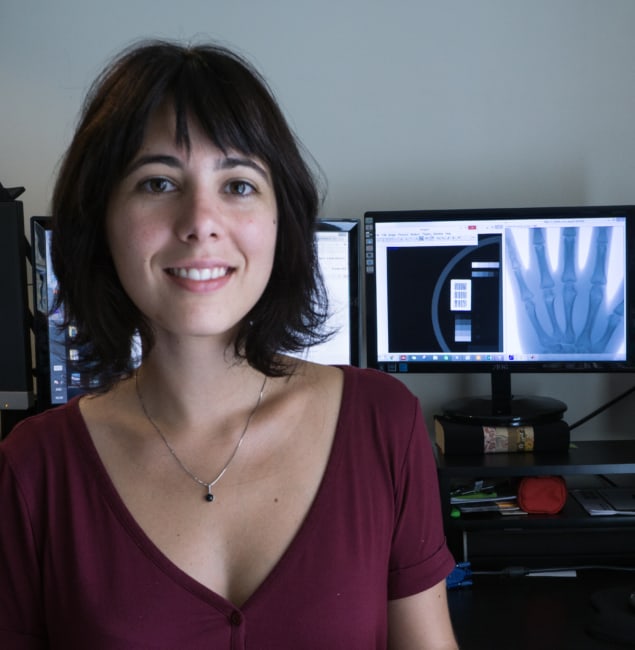

Jude Dineley interviews Elena Marimón Muñoz, detector physicist at Varex Imaging in the UK. Muñoz is one of eight physicists profiled as part of a specially commissioned article on forging a career in medical physics.

“It’s how close medical physics is to everyday life,” says Elena Marimón Muñoz, summing up her passion for the field. After five years studying largely pure physics in her hometown of Valencia, Spain, Muñoz enjoyed radiation physics, but was more interested in applications. “I had a couple of subjects related to medical physics and I really liked it.”

Keen to live overseas, she completed a master’s in medical physics at the University of Surrey, followed by a six-month placement at Dexela in London, now a subsidiary of Varex Imaging. The company develops X-ray detectors for imaging systems such as computed tomography (CT) scanners. Muñoz enjoyed the work and is still there as a detector physicist more than six years later. Part of a multinational image processing team, she assesses new detectors during the design process, analysing the quality of images they produce.

In June, Muñoz also submitted her engineering doctorate (EngD) thesis based on two research projects she did at Dexela. An EngD is an industry-sponsored PhD-equivalent degree for those more inclined towards industrial R&D. “I like industrial research because it enables me to contribute to new innovations, but provides more stability than academia.”

In one project, Muñoz’s research was in breast cancer screening, working to improve image quality and cut the radiation dose to patients by removing scattered X-rays. “Scattering is a big problem in mammography because it increases the noise and makes diagnosis more difficult,” she says.

To remove scatter, conventional detectors use expensive metal grids that also absorb the valuable non-scattered photons used to construct the image. Instead, Muñoz used post-processing, predicting the scatter using Monte Carlo simulations, then removing it from the images. “Breast cancer affects over a million women every year and early detection is key to improve the outcome of treatment. It’s very gratifying to work on something that could help diagnose women better.”