Entanglement is a key resource for quantum computation and quantum technologies, but it can also tell us much about a computational problem. That is the conclusion of a recent paper by Achim Kempf and Einar Gabbassov – who are applied mathematicians at Canada’s University of Waterloo and are affiliated with Waterloo’s Institute for Quantum Computing and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Writing in Quantum Science and Technology, Gabbassov and Kempf show how entanglement plays a fundamental role in determining both the efficiency and the hardness of quantum computation problems.

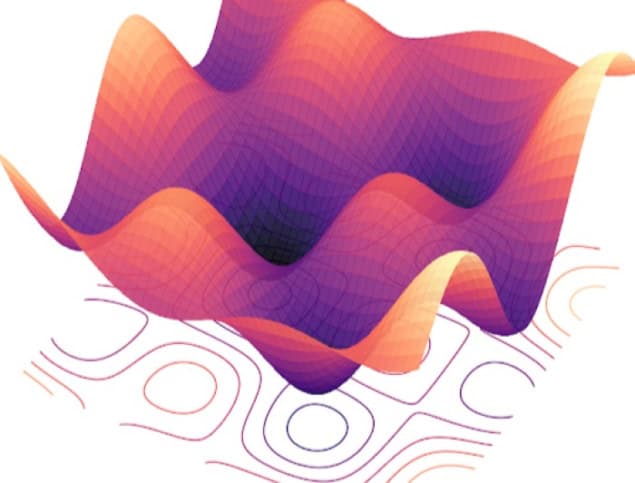

They considered the role of entanglement in adiabatic quantum computing. This considers a landscape of hills and valleys (the problem) where the shape of the landscape depends on the problem to be solved. A point on the landscape represents a candidate solution to the problem. This could be a configuration of possible states of three qubits, for example, or “a possible schedule for truck routes, or a particular shape for a pharmaceutical molecule” says Kempf. The actual solution to the problem is then the lowest (deepest) point in the landscape, which corresponds to the lowest energy point (the minimum point or minima).

This minima is easy to find if the landscape is smooth and has only one valley. The problem is harder if there are multiple valleys (a rugged landscape) since you might get stuck in a valley you believe to be the deepest, but which is not, and then you would have to climb out of it.

In a classical computation, every possible valley must be checked one-by-one to find the deepest one. However, Kempf explains that “in adiabatic quantum computing, the computer keeps track of all the valleys at once, by connecting them internally using entanglement”. Classically, many possibilities just means many independent guesses of the deepest valley. With quantum effects, when one part of the landscape shifts, it affects the whole landscape all at once. He explains that instead of checking each valley one-by-one, we can check them all simultaneously, significantly increasing the speed at which the lowest point in the landscape is found.

Shapeshifting landscape

When given a difficult problem with many valleys, there is a risk of getting stuck in a valley that is shallow and not being able to climb out and find the lowest energy state. Adiabatic quantum computing gets around this issue through a clever shapeshifting of the landscape.

The process starts with an easy landscape, comprising only one valley. Since the solution is simple, the the deepest valley corresponding to the lowest energy state is occupied quickly. Gradually the landscape is changed to contain more and more valleys, more closely approximating the more complicated landscape whose lowest point is the solution.

The lowest point changes with each change in the landscape, but the trick is that if the changes in the landscape are small enough, the deepest part of the landscape and therefore the lowest energy state will always be occupied. This is the basic principle of adiabatic quantum computing often used in resource allocation, routing and logistics, and machine learning where there can be huge numbers of possible variable configurations.

Difficulty and computation time

In their work, Gabbassov and Kempf explore how the amount of entanglement required to find the deepest valley links to the difficulty and time needed to complete the problem.

A difficult problem would be a rugged landscape consisting of multiple valleys of similar depth located far apart from one another. To occupy the lowest energy state, we need to occupy all these valleys simultaneously. The entanglement needed to do this is greater since the interconnectedness between the valleys is harder to maintain when they are further apart (they have a large Hamming distance). The problem is also harder to solve since it is more difficult to discern which of these valleys is the deepest when they have a similar depth – being close in energy. This added difficulty is reflected in a need for a greater amount of entanglement to keep track of the valleys but also in a greater amount of time needed to distinguish the depths of the valleys to find the deepest one.

Could silicon become the bedrock of quantum computers?

Gabbassov and Kempf show that a large amount of entanglement is needed at these difficult, bottleneck points of the computation. This makes it even more difficult to keep track of the valleys and more time is required to avoid falling into the wrong one. This is also where classical computation would normally slow down. Quantum effects are therefore most valuable and are most crucial at these points, proving essential for identifying when and where adiabatic quantum computation can provide a genuine advantage over classical methods.

Kempf summarizes this as, “the hardness of any computational problem, directly translates into the corresponding widespreadness of entanglement the quantum computer needs to keep track of all the valleys so that it can find the minimum point. Calculational hardness therefore means the need for sophisticated entanglement. Since entanglement is a precious and fragile resource, a hard problem that requires a lot of it can only be solved slowly.”

Entanglement therefore proves to be a useful tool not just for significantly increasing the computational speed of problems but also in characterizing problem difficulty and computation speed. As Gabbassov notes “if we want to devise faster quantum algorithms, we should look not just at the amount of entanglement but also at how this entanglement redistributes/flows” and therefore the structure of the problem. Their work shows that the amount of entanglement used as a resource is more subtle than just providing a general computational speed-up.