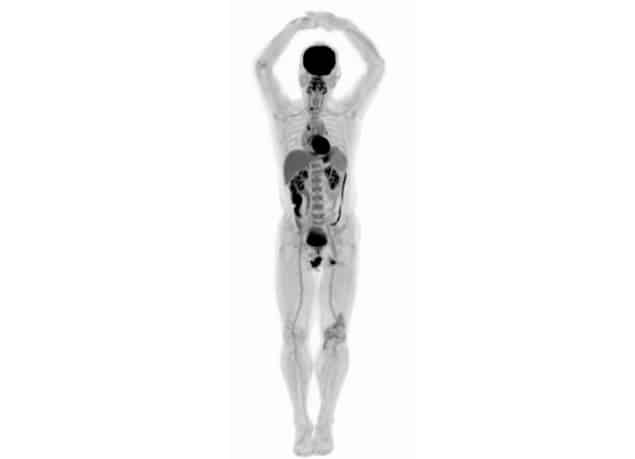

The EXPLORER PET/CT scanner is the world’s first medical imaging system that can capture a 3D image of the entire human body simultaneously. The scanner, designed and built by the multi-institutional EXPLORER consortium, has now produced its first human images.

The brainchild of UC Davis scientists Simon Cherry and Ramsey Badawi, EXPLORER has a far higher sensitivity than current commercial scanners and can produce a whole-body diagnostic scan in as little as 20-30 s. It can also create movies that track radiolabelled drugs as they move around the body. The machine can scan up to 40 times faster, or use up to 40 times less radiation dose, than current PET scans, making it possible to conduct repeated studies in an individual, or dramatically reduce dose in paediatric studies.

“The trade-off between image quality, acquisition time and injected radiation dose will vary for different applications, but in all cases, we can scan better, faster or with less radiation dose, or some combination of these,” Cherry explains.

Imaging first

Badawi and Cherry first conceptualized the total-body scanner 13 years ago. In 2011, a $1.5 million grant from the National Cancer Institute allowed them to establish a consortium of researchers and other collaborators. And in 2015, a $15.5 million grant from the NIH enabled them to team up with a commercial partner and build the first EXPLORER scanner.

The first human images were acquired in collaboration with Shanghai-based United Imaging Healthcare (UIH) — which built the system and will manufacture the scanner — and Zhongshan Hospital.

“While I had imagined what the images would look like for years, nothing prepared me for the incredible detail we could see on that first scan,” says Cherry. “While there is still a lot of careful analysis to do, I think we already know that EXPLORER is delivering roughly what we had promised.”

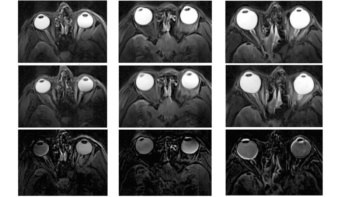

The team used the scanner to image the delivery and distribution of fluorodeoxyglucose in real time. The resulting movie shows how, in the first few seconds after injection into a leg vein, the tracer travelled to the heart and was then distributed through the arteries to all organs in the body. Gradual accumulation of the glucose could be seen in the heart, brain and liver.

“The level of detail was astonishing, especially once we got the reconstruction method a bit more optimized,” says Badawi. “We could see features that you just don’t see on regular PET scans. And the dynamic sequence showing the radiotracer moving around the body in three dimensions over time was, frankly, mind-blowing. There is no other device that can obtain data like this in humans, so this is truly novel.”

Developing the world’s first full-body PET scanner

UC Davis is working with UIH to get the first system delivered and installed at the EXPLORER Imaging Center in Sacramento, and the researchers hope to begin research projects and imaging patients as early as June 2019.

“I don’t think it will be long before we see a number of EXPLORER systems around the world,” says Cherry. “But that depends on demonstrating the benefits of the system, both clinically and for research. Now, our focus turns to planning the studies that will demonstrate how EXPLORER will benefit our patients and contribute to our knowledge of the whole human body in health and disease.”