Universe or Multiverse?

Bernard Carr (ed)

2007 Cambridge University Press

£45.00/$85.00 hb 310pp

Up until 80 years ago the astronomical community was embroiled in an argument about our place in the universe. On one side was the perennial idea that we were all there was — that our galaxy was a single lonely island in a vast empty cosmos that spanned out to infinity. Telescopes revealed distant smudges of light — so-called nebulae — but these were explained as merely ill-resolved clouds of gas in the Milky Way. Opposing this bleak, self-centred universe was the view that our galaxy was but one of many galaxies sprinkled throughout space. The nebulae were, in fact, our nearest neighbours, but were too far away for our telescopes to map out in sufficient detail.

Dubbed “the great debate”, this conflict lasted for over a century. The data were simply not good enough to decide between the two ideas, thus leaving a fertile ground for theorizing and speculation. Things came to a head in April 1920 in a historic confrontation between the astronomers Heber Curtis and Harlow Shapley at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. The debate was finally settled in 1925, when Edwin Hubble measured the distance to the Andromeda Nebula and found that it was much too far away to belong to the Milky Way and so must be a galaxy in its own right. We now know that we live in a many-island universe, with the Milky Way being just one of a billion galaxies in our visible horizon.

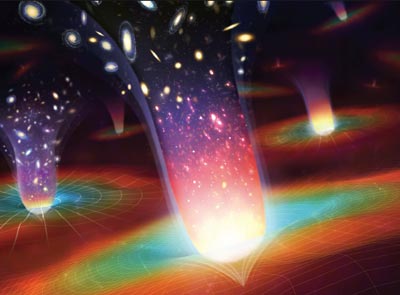

Fast forward 80 years and things look a lot less straightforward. Galaxies are mere peanuts in the grand scheme of things: the great debate is now being played out on a larger scale as today’s cosmologists ask whether we live in a universe or a multiverse. In other words, is our universe — the thing we measure and model, prod and picture — all there is? Or is it just one element in an ensemble of many universes, each of which has different properties, histories and behaviours.

Universe or Multiverse? is a new collection of essays, edited by Bernard Carr of Queen Mary University of London, that attempts to address this question. Cambridge University Press has published several cleverly edited collections of essays on theoretical physics over the past few decades, a notable example of which is Three Hundred Years of Gravitation, edited by Stephen Hawking and Werner Israel, which celebrates Newton. It was published 20 years ago but I find it is still a wonderful collection of ideas and texts to dive into when I wish to immerse myself in gravity. Universe or Multiverse? is up there with the best of these compendia. It is probably the most comprehensive tome on the subject around at the moment and, like the others, I imagine it will have a long shelf-life.

Universe or Multiverse? consists of 28 essays neatly woven together to cover a wide range of physical and philosophical issues. It has a colourful cast of characters, with die-hard particle physicists discussing the testability of string and M-theory, cosmologists expounding the successes of “inflation” and rejoicing in the “golden age” of precision cosmology, and a plethora of essays on how we fit into all of this. The range of contributions is too wide for me to do real justice to it here, but I can highlight a couple of notable examples.

The anthropic principle crops up in many of the essays. This states that we see the universe that we see because we would not be around it to see it if it were any other way. Carr clearly explains how this point of view emerged in the 1970s through his work with Martin Rees at the University of Cambridge, in parallel with that of Brandon Carter, also then at Cambridge. Since then, the anthropic principle has generated a number of disciples among the supporters of inflationary cosmology.

The simplest model of inflation, as advocated in a contribution by Andrei Linde from Stanford University in the US, argues that we live in a patch of the universe that underwent a period of incredibly rapid expansion shortly after the Big Bang. What was originally a microscopic piece of space swelled up to cosmic scales within a tiny fraction of a second. But there should also be infinitely more patches that have undergone the same process, and each is causally separate, meaning that they can be considered different universes. This implies that our universe is surrounded by other universes — possibly with different features and laws of physics — but which all belong to a massive, frothing space–time: the multiverse. Glorious as this theory of the universe may be, however, it lacks one of the most fundamental requirepredictability. If we can never access these other universes, then we can never know whether any predictions we make about them are correct.

The multiverse theory also poses the thorny question of why we do not live in a different patch of space with different properties and laws of physics. It is here that the anthropic principle comes in to save the day. It allows us to, at least statistically, argue why the patch of the multiverse we live in looks the way it does. A clutch of essays — for example those by John Donoghue from the University of Massachusetts and Renata Kallosh from Stanford University — looks sympathetically at this point of view, but I would highlight Lee Smolin’s negative appraisal of this line of thinking. In a thoughtful piece of writing, Smolin, who is at the Perimeter Institute in Canada, unpicks the true operational meaning of the anthropic principle and shows that it is unfalsifiable, i.e. that it does not make testable predictions. He goes on to argue that it is misapplied in many cases and he proposes alternative, falsifiable ways to answer the question of why the universe we observe should be as it is. These alternatives are speculative, I must add, but are nevertheless worth thinking about in some detail.

Another ominous cloud on the horizon is the notion of “the landscape”. For decades it has been known that string theory has an inordinate amount of possible solutions and it is now argued that there are 10500 possible vacuum geometries in which we might reside, dubbed “the landscape” (see “Stringscape”). This jeopardizes the noble goal of ending up with one all-encompassing theory from which we may predict everything, from the shape of the cosmos to the mass of the electron. If there really are these many possibilities, should we just give up? As the particle theorist Steven Weinberg from the University of Texas at Austin writes in the conclusion to his essay, we may have to “resign ourselves to a retreat, just as Newton had to give up Kepler’s hope of a calculation of the relative sizes of planetary orbits from first principles”.

Universe or Multiverse? covers these frightening times in the most fundamental field in physics with a series of insightful essays. Short of actually conjuring up a new Edwin Hubble to take some data and resolve our place in the cosmos, this well-constructed collection of writings is the best we can possibly hope for in the era of this new great debate.