A moment of distraction over the dishes sends Andrew Ferguson on a journey of literary discovery

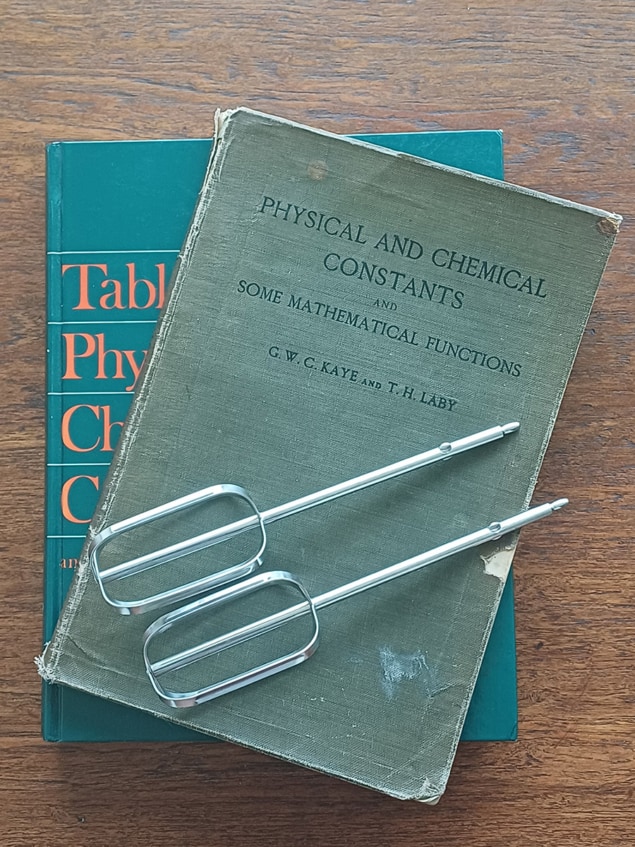

On a recent Friday night, as I was tidying the kitchen after dinner, I glanced down at Kaye and Laby. No, these aren’t the names of my cats, but rather a reference to my well-travelled 14th edition of the book Tables of Physical and Chemical Constants. Earlier in the day, you see, I’d been looking up the thermal properties of titanium and had neglected to put it back on the shelf.

For anyone unfamiliar with the book, well, the title says it all really. Inside you can find all sorts of information about the physical and chemical properties of materials – from the acoustic attenuation of aluminium to the boiling point of benzene. Essentially, it’s a distillation of information for the practising physicist.

It’s also a book you can easily get lost in. Having found the thermal conductivity of titanium, for example, I ended up musing over the similarly low value of the same for plutonium. At this point in the evening, instead of returning the book to its proper location, I had disappeared down a rabbit hole.

I’ve had this particular volume for perhaps 20 years and it has been a helpful reference for undergraduate teaching and research. However, that evening I realized that I had no idea who Kaye and Laby were, or how their book came about. And, of relevance to this piece, I wondered what a first edition looks like and how much it would sell for.

The reason for this rather materialistic thought was that earlier in the week I had stumbled upon the website of a London-based purveyor of rare books. They sell, for example, signed first editions of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, for more than I make in a year. My curiosity had been piqued.

A few minutes after the kitchen had been made respectable, I was checking on eBay, where sure enough someone was offering a cloth-covered first edition of Kaye and Laby. The starting bid was about the cost of a round of beer and there were two days left in the auction. My heart started to beat a little faster: I had gone from being ignorant about the history of Kaye and Laby to becoming emotionally invested in an Internet purchase.

George William Clarkson Kaye and Thomas Howell Laby, I discovered, were both research students at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge in 1905, while J J Thomson was head. During their research on X-rays (Kaye) and atomic physics and physical chemistry (Laby), they collected physical data from diverse sources. Apparently, their colleagues found this compilation useful and suggested that it would be worth publishing.

But what other similar reference books were on the market at the time? By 1905, three editions of the Physikalisch-Chemische Tabellen by Landolt and Börnstein had been published by Ferdinand Springer and it is frequently referred to by Kaye and Laby. But it was in German and lacked any recent results on radioactivity and gaseous ionization. Kaye and Laby’s book, first published in 1911, became a success, and a second edition followed five years later.

An unelementary affair: 150 years of the periodic table

Kaye and Laby ended up collaborating on nine editions of their work. In 1948, after both their deaths, a committee was set up by their publisher to continue revisions of the book, which still went by the names of the original authors. The final, 16th edition was published in 1995 and can be found online in an archived, unmaintained form.

A good source on the first edition of Kaye and Laby is the 1997 article in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society. The author – Anthony Constable – describes his excitement at finding a copy in good condition in a bookshop. As he put it, he had “come to treat it with the reverence that one normally reserves for precious old scientific instruments”.

I am fortunate to be able to hold a rather slim volume that is part of scientific history

Almost unbelievably to me, there were no other bidders in the online auction and I am now fortunate to be able to hold a rather slim volume that is part of scientific history. The book takes me back to a time when physics was changing apace and becoming part of the narrative of the 20th century. It was published between Einstein’s relativities, before the Bohr model of the atom, and in the same year that Marie Curie won her Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

I love the almost poetic statements interspersing the terse tables of data, which bring an understated style to the substance. In the section on photometry, we can read that “A candle is visible at about a mile on a clear dark night.” But could there be out there somewhere a Kaye and Laby first edition containing Thomson’s signature? Now, that would be a find.